An Apple Pie From Scratch, Part VIIb: Geology and Landforms: Erosion and Deposition

|

| Tower karst along the Li River, China. chensiyuan, Wikimedia |

As tectonic forces work to raise land (well, not always, but they are the main forces that do so) erosional forces are constantly working to flatten it out again. For various reasons they rarely do so perfectly or evenly, and the many specific interactions of tectonics and different erosional forces leads to the diversity of terrains we have on Earth today.

One important point to emphasize is that geology is a dynamic process, and the world we see today is a snapshot of many ongoing processes of transition and change. Many areas have terrain that looks nothing like what we’d expect to see once erosion had fully run its course, and some have been shaped by erosional forces that are no longer active today. Rivers may follow courses not possible had they started carving out channels today, mountains may stand long after the tectonic forces responsible for them have died away, and deserts may bear the scars of seas and rivers that no longer exist. I won’t get into all the ways different forces and processes may interact here, but bear in mind that no landform exists in isolation and may exist at any point in a dozen overlapping states of transition.

As with the last post, I’ll run through a list of the most common or notable landforms caused specifically by erosion and deposition, describing their general location, appearance, dimensions, and any ecological or social impacts.

Types of Erosion

There are numerous types of erosion which work in various ways, but generally speaking rock or sediment that is more exposed tends to be removed, broken down—usually into clasts, fragments of rock, but sometimes completely dissolved in water or other fluids—and then transported until it arrives in a more sheltered region, where it is deposited. Because gravity plays some role in most erosion processes, the tendency is for material to move downhill, such that higher regions are eroded down and lower regions are filled in, and all regions trend towards a flat plain (though there are various exceptions and nuances).

But elevation isn’t the only factor here; a small outcrop in a lowland plain may be eroding down, while an isolated valley in the highlands may be filling in with sediment.

To avoid any confusion, I’ll divide the surface into source regions, which are losing material on average, and destination regions, which are gaining material on average. There’s a bit of grey area, and the dividing line between these can shift with the seasons or even with the daily weather; but in general it’s an easily identified distinction that we can find in any type of terrain, and in many cases we can identify a fall line on the flanks of mountains, where steep source terrain gives way to flatter destination terrain.

We can also define a base level, which is the elevation below which erosion essentially stops, because there are no available destination regions below that level where material can be moved into (e.g., once a pebble rolls down to the nadir of a valley, there’s nowhere lower for it to go). For much of the world this is sea level (sort of; erosive forces on the sea bottom will continue to move material to deeper areas, but the dominant erosive forces on land will generally stop once they reach sea level, and the former are much stronger), but in many areas it can be much higher, or in a few cases even lower.

Any given part of the world will be influenced by multiple erosive forces, but for our purposes, I’ll break down the world’s terrain into 4 major categories dominated by different main erosive forces (each containing their own internal source and destination regions):

- Fluvial terrain dominated by erosion from

the movement of liquid water in the form of rain, runoff, streams, rivers, and

lakes.

- Glacial terrain dominated by erosion from

the formation and movement of ice in the form of snow and glaciers, or

meltwater flowing directly off those glaciers.

- Eolian terrain dominated by wind erosion

in the absence of strong fluvial or glacial erosion.

- Coastal terrain dominated by erosion from waves, tides, and other processes unique to coastlines.

Again, many areas are affected by a combination of these

erosive forces, and some features arise specifically from their interaction—and

bear in mind that, as with mountains in the last part, this categorization is

my own invention, and a formal geological classification scheme would probably

include a lot more nuance. Erosion can also be driven by plant growth, animal

activity, mass wasting (gradual collapse of slopes due to gravity after being weakened by other forces), seasonal and daily

shifts in temperature and ice formation, earthquakes, meteorite impacts,

gradual chemical processes, and even solar wind and chemical alteration by

sunlight (not terribly important on Earth, but a major source of erosion on

airless bodies like the moon).

|

| A more detailed breakdown of common depositional environments. Mikenorton, Wikimedia |

Fluvial

|

| Horseshoe Bend, Utah. Paul Hermans, Wikimedia |

Terrain dominated by erosion from the movement of liquid water. This is the most widespread terrain, and really almost all of Earth’s land area experiences some amount of fluvial erosion. But in this case I’m referring specifically to terrain where fluvial erosion dominates over all other types, such that topography is limited by a set of “rules” imposed by the nature of water flow and fluvial erosion.

To understand these rules, think of the experience of a single water droplet raining down somewhere on land. Presuming it’s not absorbed into the soil, the droplet will run downhill, following the steepest possible path at all points (not always the steepest overall path to the sea, but travelling down the greatest incline from its current position). Based on this simple behavior, we should be able to find a single path that a water droplet will necessarily always follow if it starts from a given point; place a water droplet at the same point on the side of a mountain twice, and it should follow the same path to the sea both times.

Now, if we place water droplets in multiple locations, they’ll each follow their own paths, but sometimes those paths will converge; if we drop water on either side of a mountain valley, we should expect the droplets to meet somewhere in the middle. And once two droplets arrive at the same point, they should follow the same path thereafter, just as two droplets starting from the same point would. So the paths of these droplets can converge, but not diverge.

If we pick any given point on the surface (that isn’t directly on a peak or ridgeline) and mark out all such paths that pass through it, we’ll find that there is some area uphill of this point covered by these paths, called a drainage basin (a.k.a. catchment area, impluvium, river basin, watershed in North America), and a single combined path leading out, called the outlet. All water that starts anywhere in the drainage basin will pass through the outlet, so the larger the drainage basin, the more water runs through the outlet (accounting for local rates of precipitation, and neglecting evaporation and groundwater flow); a small drainage basin may only produce occasional runoff, a large one will feed a raging river. Major river outlets to the sea will have the largest drainage basins of all, and often geographers will divide up landmasses into the drainage basins of these major river outlets.

Between drainage basins are divides (a.k.a. watersheds in Europe), lines across which no water flows, lying along ridgelines that are higher than the terrain on either side. The divides between large drainage basins are typically the peaks of large mountain ranges, but between smaller drainage basins they can be moderate hills or just subtly higher terrain. Mountain ranges typically have a divide running their entire length.

|

| Asybaris01, Wikimedia |

Now, you might wonder why our water droplets can’t just all find their own paths to the sea without converging, or what happens if water reaches the bottom of a pit, and this is where erosion comes into play. As water travels across the land surface, it will tend to break down some of the surface rock or sediment and carry it along with it. The more water moves along a particular path—and the faster it moves—the more of the surface it will erode away. A lot of water following one path will carve out a channel, and the sides of the channel will be steeper than the surrounding landscape, such that any nearby water will tend to flow down into it. This both increases the amount of water moving through the channel, carving it deeper, and forms new tributary channels leading into it—which will form their own tributaries, and so on, spreading out across the landscape. This ability for a channel to carve uphill, against the direction of water flow, by changing the shape of the slopes above it is called headward erosion.

Thus, even if you begin with fairly smooth topography with

no large channels for water to follow, fluvial erosion will tend to create a

series of converging channels, such that water ultimately flows out of a small

number of outlets. Headward erosion even allows one large river to “capture”

neighboring streams: as their tributary channels extend upstream, one may breach

the divide between the river and stream, at which point the stream’s water will

start running out the deeper river channel instead of its former, shallower

outlet, turning the stream into a tributary of the river—thus further

consolidating the flow of water across the region into fewer outlet channels.

Part of the stream formerly downstream of the capture point may even switch

direction to flow into the deeper river.

|

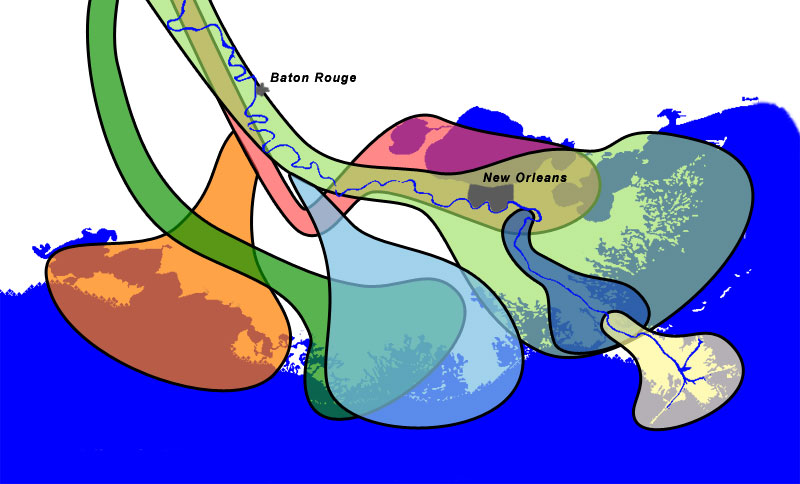

| Source |

But stream capture tends to work best on flat ground, and can only divert streams so far; a stream running 10 kilometers to the sea over a steady slope generally can’t be redirected 100 kilometers away to another outlet. A stream also generally can’t be made to cross a mountain range, even a very old or moderate one, as this would either require it to be running uphill at some point during its formation, or for upstream erosion to cut a channel through the mountain range that is lower than the terrain on the far side—and by the time that could happen, the range would be so eroded down as to essentially not exist anymore. There are some few exceptions where a river is older than the mountains it’s crossing and has continuously eroded down its channel as fast as the mountains have risen up; or an enclosed basin is formed such that water flow must cut through the mountains somewhere to reach the sea.

Anyway, the result is that where a major divide such as a mountain range is close to the sea, it will tend to have many small drainage basins on its seaward side; but the broader the coastal plain, the more of its area will tend to be dominated by a few large drainage basins.

|

| Drainage divides of South America, with the Andes dividing the many small basins of the west coast from the large basins of the east coast. HydroSHEDS |

Now, if water comes to the bottom of a pit, with uphill slopes in all directions, it naturally comes to a stop and cannot flow any further. But more and more water will gather in the pit, until it overruns the the rim of the pit at its lowest point; the escaping water will begin cutting out a channel, and continue doing so until the bottom of the channel is lower than the deepest point in the pit. Thus, given time, fluvial erosion will act to eliminate such pits and enclosed basins, such that from any point on land, you should be able to reach the sea travelling only downhill.

And now let’s see how deposition figures into this: as water erodes away at rock, it breaks it into clasts, and the size of clast that can be carried depends on the speed of water flow, which itself depends on the slope of the channel the water runs down. A river running down the side of a mountain may push cobbles and pebbles along, but on reaching a flat plain it may only be able to carry fine silt. As the river passes over ever shallower terrain and slows down, clasts too heavy to carry will be deposited. To some extent this can fill up a river’s channel, but erosion is still generally stronger than deposition at the fastest-flowing part of the river, and as its channel fills a river will shift course to any lower nearby terrain, such that deposition is spread across a broader region.

So all the general principles we’ve established still hold: Rivers will form converging channels and erode out pits (or fill them in with deposited sediment) such that all points have a downhill path to the sea. But as I mentioned before, the competing forces of erosion and deposition divide fluvial terrain into source regions, with steep, fast-flowing rivers such that erosion is dominant and forms deep channels; and destination regions, with shallow, slow-flowing rivers such that deposition is dominant and forms broad plains (more formal sources will sometimes distinguish between bedrock rivers and alluvial rivers, which more-or-less line up with my source/destination categories, and some also distinguish an intermediate transport region where there is relatively little erosion or deposition). Individual channels will tend to have a curved profile from source to outlet, with progressively smaller clasts depositing along their length.

|

| Trista L. Thornberry-Ehrlich, Colorado State University |

Hopefully you’re starting to get an emerging picture of how fluvial terrain will appear: landmasses will be split into drainage basins occupied by many tributaries feeding into a single outlet to the sea, divided by mountain ranges across which rivers usually do not cross. These mountain ranges will be cut away at their peaks by erosion, while deposition fills in valleys at their base and extends the landmass into the sea, ultimately dividing the land into rugged highlands and broad coastal plains, with a fall line where the rising surface of deposited sediment meets the falling surface of the eroding rock.

But now that we’ve built this model, it’s time to see where it fails. Everything I’ve discussed so far has been based on a few key assumptions which are mostly true across most of Earth’s surface, but not always:

First, that water raining down anywhere on land must ultimately flow back to the sea. This is generally true in areas where precipitation outruns evaporation and soil is saturated with groundwater, and it ensures that any enclosed basin will eventually fill with water until it overflows its banks and forms an outlet channel. However, in drier areas like deserts and highland plateaus, precipitation may be low enough that all water that collects within a basin ultimately evaporates away, and so the basin never completely fills with water. We’ll discuss these endorheic basins in more detail later.

Second, that all water starting at a given point must follow the same path to the sea. At broad scales this is mostly true and means that river’s can’t split, only converge into ever large rivers. But within a river itself the water obviously cannot all follow the exact same path as it has some volume (turbulent flow within rivers also adds a chaotic element to the movement of water, as opposed to the strictly predictable approach I’ve been using so far). Thus, if a river encounters some obstacle like a large rock, the water within it may diverge and follow different paths around the rock. More commonly, the water level in a river may rise above the banks of its channel and flow into a new channel; water near the bottom of the river must still move down the older, deeper channel, but water near the top of the river can flow into the new channel while still moving “downhill”. There are various cases in reality where this happens; usually it forms an anabranch, a smaller parallel stream that eventually rejoins the river (because the river usually overflows into one of its own tributaries).

But in a handful of cases, a stream splits into two distributaries which part ways and never rejoin, ultimately flowing into different outlets and sometimes even completely different oceans. For example, in Wyoming in the US at the Parting of the Waters, North Two Ocean Creek splits into two streams: one flows east into the Yellowstone River and on to the Missouri, the Mississippi, and into the Gulf of Mexico and thus the Atlantic Ocean; the other flows west into the Snake, the Columbia, and into the Pacific Ocean. Thus, the legendary Northwest Passage between the oceans does actually exist, and if you had a canoe and a strong arm you might be able to pull yourself along the centimeters-deep creek and so cross the continent without stepping onto land. Clearly this has major implications for international trade.

Pretty much all such dividing streams are similar: very small and young, or often present in dry areas with intermittent flow (the largest dividing river, in the Amazon basin, is in a flat, marshy region with frequent flooding). Water flow through the distributaries is never perfectly equally, so eventually one will cut a deeper channel than the other. This causes more water to flow through it and less through the competing distributary, and thus it forms an even deeper channel, and so on until flow through the other channel stops. Thus, these dividing streams are ultimately temporary features, and each should abandon one of their distributaries over time (hence them being common in dry regions with slow erosion and seasonal flooding). A large, mature river shouldn’t split in this fashion, though it may occasionally form small anabranches as its course shifts and it encounters obstacles or floods over its banks.

Of course, this introduces its own assumptions: that river channels and water level are relatively stable, such that new channels form rarely. Again, this is mostly true on large scales, and even on small scales in mountain streams and lowland rivers. But if channels or water levels can shift more rapidly, then anabranches may form as quickly as they’re abandoned, such that some are present at all times. This can happen due to loose soil and rapid deposition in braided rivers or tidal action and similarly rapid deposition in river deltas.

We’ll discuss both of these soon, but in short, these splits are limited in extent and neither will lead to the formation of large distributaries leading to distant outlets: for the former, channels within the river can split, but any distributaries that diverge too far from the main course of the river will eventually be abandoned in favor of shorter channels; and for the latter, the river is already so close to the sea that there’s not far the distributaries can go, and again there's a tendency to favor shorter channels in the long term.

To sum up this whole discussion, here’s a quick review of the major “rules” of fluvial terrain, and their exceptions:

- You should be able to reach the sea travelling only downhill from any point on land.

- Unless precipitation is too low to overcome evaporation, in which case endorheic basins may form.

- Rivers and streams can converge to form tributaries, but never diverge.

- Except temporarily to form anabranches and distributaries, or where rapid channel migration or water level change forms braided rivers and river deltas.

- Rivers will tend to converge into a few outlets rather than run parallel.

- But less so on steeper slopes, when close to the sea, or when divided by highlands.

- Rivers do not cross mountain ranges and highlands from one side to the other.

- Unless the river channel is older than the mountain range and has eroded down as fast as the mountains have risen, or there is an enclosed basin with no alternative outlet (and enough precipitation such that it doesn’t become an endorheic basin)

- Rivers will begin steep near their source and then flatten out as they approach the sea.

- Unless they pass through flat areas in mountain valleys or recently uplifted plateaus, in which case their profile may be more complex.

With all that established, let’s look at the landforms we might encounter in fluvial terrain, and in particular the major forms of rivers, proceeding generally downstream from source to sea. Rivers are the defining features of fluvial terrains, and may be worth including even if you’re not going to work out all the topography of your world.

Dendritic Drainage

|

| Yarlung Tsangpo River, Tibet. NASA |

This is essentially the default form for rivers in source regions: stream channels converging towards each other but not simply running directly at each other, and usually with no more than 2 streams meeting at any one point, forming a structure that appears broadly similar to tree branches. This dendritic pattern results from a balance between fluvial erosion favoring shorter stream paths (as they’re steeper and so carve out deeper channels) and disfavoring sharp turns in flow direction (as this causes excessive erosion on the outer bank that will force the channel to migrate to a straighter course).

|

| Marshall Wolff |

This same pattern will form at essentially all scales, so long as the underlying terrain is all made of roughly the same material and all erodes at the same rate. It’s even present in regions without a consistent source of water: The topography of arid regions and mountaintops still show dendritic patterns from erosion during rainfall.

However, if there is some variation in the underlying material, such that it erodes at different rates, a few other patterns can result:

- Trellis

drainage forms where there are parallel valleys or ridgelines, such as in a fold-and-thrust belt. Within each valley, streams will flow straight off the ridges and converge in a main stream running down the center; these main streams may then either cut through gaps in the ridges to converge or converge past the ends of the ridges, depending on the overall slope of the terrain (though often it's a mix of both).

- Parallel

drainage may form where there are more closely-spaced, parallel faults: streams preferentially form along the line of

easier erosion (or between lines of harder erosion) and then converge on flatter ground.

Tshf aee, Wikimedia - Rectangular

drainage is a rare variety that forms where faults have formed at right

angles to each other, such that streams follow angular paths alternating

between the two fault directions.

- Radial

drainage forms around an isolated, steep peak such as a stratovolcano, with

streams running out in all directions directly down the steep slopes. If there

is flat ground around the peak, they may then join together downstream.

V-Shaped Valley

|

| Stillach River Valley, Germany. Kauk0r, Wikimedia |

The typical cross-section of a stream channel in a source region. As a stream erodes down a channel, the walls of the channel will collapse into the stream, due both to fluvial erosion and mass wasting; collapse of material under gravity, as the stream erodes away its support from below. That collapsing material then no longer supports the material above it, and so on, all the way up to the nearest ridgeline or peak.

The eventual result is a steep, consistent slope formed on either side of the channel. The tougher and less broken-up the material, the steeper the slopes. Even a small, intermittent stream can form a broad valley this way. The v-shaped valleys of neighboring streams will form a sharp ridgeline between them that slopes down to their junction. It doesn’t take long for any source region to be completely carved up into these valleys, so the typical topography of high mountain ranges is a maze of ridgelines and channels, with steep slopes between them.

The valley walls are not necessarily all the same gradient. For one thing, there will typically be tributary channels at many points in the valley walls. For another, certain layers of tougher, more consolidated rock will resist erosion better than the material above them, forming “shelves” that jut out from the walls. Alternating layers of weaker and tougher material can form staircase-shaped valley walls. To an extent these layers will shield those below them from erosion, but if the tough layer is particularly solid it can remain in place while the layer below is eroded deeper into the slope, forming an overhang.

Often a channel can have a shallower gradient than its banks and tributaries, so some material will be deposited in the channel and form a flat valley bottom—though usually it’s much thinner than the entire valley.

Dimensions: The angle of the slopes varies depending on the material. For loose sediment the ultimate limit is the angle of repose, which is the maximum angle at which the clasts on the surface can be supported rather than rolling down the slope. For most natural sediments on Earth this is typically 30-40° from horizontal. This is independent of clast size, and somewhat dependent on gravity but not strongly, especially within the range we expect of Earthlike planets.

As a general rule (sometimes formalized as Playfair’s Law), the depth and breadth of a stream valley in a particular area will be proportional to the size and speed of the stream, and when streams converge they will tend to do so at the same gradient.

Canyon

|

| Santa Elena Canyon, Texas. Ann Wildermuth, NPS |

But the most striking cases are usually formed when a lowland plain is uplifted by tectonic forces, and a river erodes down to form a deep gorge in an otherwise flat-topped plateau. Laramide-type orogenies are ideal for forming canyons, as they cause this type of uplifting and also form ridgelines that help prevent the river from flowing out elsewhere, but it can occur with other forms of uplift as well. It also helps if the region is fairly arid—as this slows the rate at which the walls of this canyon are cut through with large tributaries and rounded down—and if there are alternating layers of harder and softer rock in the region, such that streams carve deep channels through the softer layers while erosion on the banks is arrested by the harder layers.

Often a preexisting river will continue to follow its path through the former lowlands and keep cutting down a deeper and deeper channel so long as no other, easier outlets become available. This is how the modern Colorado River cuts through terrain that is higher than any point on the river; were the canyon not there and a new river formed today, it could not follow the same path as this would require it to run uphill. Only the largest rivers can erode down fast enough to keep up with uplift in this way, hence why there are a few long canyons rather than whole drainage networks of canyons—at least at first.

Examples: Grand Canyon (US), Snake River Canyon (US), Fish River Canyon (Namibia), Yarlung Tsangpo Canyon (China), Three Gorges (China).

Dimensions: In strict terms, mountain canyons with tectonic causes tend to be the largest; some in the Himalayas are hundreds of kilometers long and surrounded by mountains peaking up to 6 km above the river surface, but these are not shear cliffs. The Grand Canyon, which has a less ambiguous top and bottom, has a similar length, a depth of up to 1.8 km, and varies between 1 and 29 km wide.

Impact: Canyons are obviously major barriers to travel, though occasional tributary rivers cutting into the walls can provide ramps to enter and exit them, and they can also aid travel through mountainous regions. In arid and highland regions they can effectively act as sheltered oases, much more fertile and hospitable than surrounding regions—many are forested in otherwise barren regions. Thus they can become population centers for both wildlife and civilizations, though some are also prone to flash flooding.

Badlands

|

| Blue Gate, Utah. DanHobley, Wikimedia |

Areas where a flat plain has uplifted and begun eroding down, as in the case of canyon formation, but significant time as passed; every little stream has had time to cut a deep canyon and these have joined together, such that rather than individual canyons cutting through a broad plateau, there are now small sections of the surviving plateau—flat-topped, steep-walled mesas—surrounded by deeply eroded terrain. Again, they’re more prominent in arid regions, as heavy rain would tend to evenly erode down the plateau to create a more rounded landscape.

Examples: Badlands National Park (US), Red Deer River valley (Canada), Valle de la Luna (Argentina), Bardenas Reales (Spain).

Dimensions: Typical regions are hundreds of km2 in size. Individual mesas can be similar in size and up to 2 km above the surrounding valleys. They can also be eroded down to thin spires called hoodoos and still be as much as 100 m high.

Impact: Because these areas are necessarily arid, they’re fairly inhospitable. But sheltered canyons and river valleys can be oases of life, and the steep cliffs and mesas make good defensible positions. This is enhanced by the inhospitability; there may be few paths an invader might take, so a well-placed fort can dominate a large region.

Intermittent River

|

| Nahal Paran, Israel. Mark A. Wilson, Wikimedia |

A river that has significant flow at some part of the year, but regularly has no water flow at all in another part, leaving a dry streambed. There are two main varieties: glacial streams fed mostly by meltwater from glaciers, such that they flow only in the warm months; and arroyos (A.K.A. wash, or wadi or oued in the arabic-speaking world, though precise definitions for all these terms varies) in arid regions that cease flowing in the dry season. Some may cease flowing only briefly, or not every year, but some ephemeral streams may flow only briefly after rainfall. Even when they cease flowing continuously, isolated lakes and ponds may remain in deeper sections of the riverbed (called gueltas in the Sahara) that may retain water even through the dry season.

In any case they still “count” as streams so far as the “rules” of fluvial erosion go, and they can carve out some fairly impressive channels given time; many canyons are formed by arroyos. But they may fill with sand in the dry season and behave more like the Eolian terrain we’ll discuss later.

Examples: Ugab River (Namibia), Sandover River (Australia). Many rivers such as the Colorado (US/Mexico) have recently become intermittent due to overuse of water in their drainage basins.

Dimensions: Usually fairly small, though the largest can be m across and run for 100s of kilometers. The inconsistent water level and loose soil often makes arroyos fairly broad and shallow when they are flowing.

Impact: When flowing, arroyos can be vital sources of water in arid regions, both for the natural ecosystem and any people in the area. Life on the shore or in the water may have adaptations to remain largely dormant through the dry season; some lungfish are able to burrow into the streambed and survive in a cocoon of mud and mucus, then reemerge when the stream returns. However, arroyos can also be prone to flash floods, if a major storm occurs upriver. Some arroyos are near-permanently dry except for occasional floods; often these are anabranches of larger rivers that occasionally overflow their banks.

Glacial streams can also flood, but overall tend to be more regular in their flow, and are less vital as water sources as they appear in cooler environments with less evaporation.

Waterfall

|

| Niagara Falls, US/Canada. Robert F. Tobler, Wikimedia |

A waterfall forms wherever a river goes over a steep cliff, but in some cases a river can form its own cliff. If a tough layer of rock overlays a weaker layer, the water can erode deeper into the lower layer and undercut the overlaying one, eventually causing it to fall and form a cliff. As this continues, a waterfall tends to migrate upriver, which can increase the height of the cliff formed as the channel downriver of the waterfall erodes faster than that upriver. This is usually how very large waterfalls, called cataracts, form. Smaller rivers may form a deep-walled ravine if they follow a fault.

|

| Cradel, Wikimedia |

The water at the bottom of the waterfall will tend to erode out its immediate surrounding faster than the slower-moving water downriver, so often a waterfall will have a plunge pool at its base. But if it’s a fairly small stream carrying a lot of sediment and there is flat ground at the base, then it may instead form an alluvial fan, which we’ll discuss in a moment.

Examples: Niagara Falls (US/Canada), Angel Falls (Venezuela),

Dimensions: The highest waterfall, Angel Falls, is 979 m high, but it’s fed by a fairly small river. Cataracts top out at about 100 m, but can be several kilometers wide.

Impact: Waterfalls are, of course, major barriers to boat travel along rivers. Some early river valley civilizations like the early kingdoms of Egypt had trouble extending their power beyond cataracts in the highlands. Nowadays, canal and lock networks are sometimes built to allow for riverboats to circumvent them.

Braided River

|

| Rakaia River, New Zealand. Andrew Cooper, Wikimedia |

A broad, shallow river containing many small anabranches, somewhat resembling braided rope. Generally speaking this happens when a river’s slope suddenly decreases, often when passing from a source region to a destination region. The river slows and deposits out much of its sediment on the riverbed, such that broadens and shallows. But the sediment isn’t deposited evenly: where the river bends, the water moves faster on the bank on the outside of the curve than on the inside bank, so sediment is deposited at the inside bank while it is eroded away at the outside bank. This deepens the curve, both increasing the difference between banks and causing the whole river to move laterally relative to the overall direction of flow.

This process happens to all rivers in destination regions, but braided rivers are still flowing fast enough that erosion at the outside bank is too rapid for the river to settle into a single channel, and minor deviations quickly develop into deep curves. Deposition on the inside bank forms bars of sediment, but they’re fairly low such that a moderate rise in water level can easily overflow them and form new channels across them. Many of these channels may be abandoned once water level drops again, but if a large channel forms along a shorter path than the main existing channel, it will be be favored by water flow and eroded slightly deeper, until the old channel is abandoned.

This process plays out at different rates and scales in many different places across the river, such that at any given time the river is a tangle of channels of various sizes and sometimes there may not even be a single “main” channel clearly larger than the rest. Still, because water generally prefers to flow through the straightest path available (as it’s the steepest), there’s a limit to how far any of these anabranches can wonder from the main path of the river before they’re abandoned, such that they usually can’t diverge from it completely (if they do, it’s usually because they eroded through some obstacle to create a shorter path to the river’s outlet, and eventually the whole river will shift over to that new course). Generally these temporary “subchannels” all lie within a single broader channel lower than its surroundings. Some rivers are only seasonally braided; filling out their whole channel in the wet season, but then splitting into small subchannels on the riverbed when water level drops in the dry season.

This particular balance between high deposition on the riverbed and high erosion on the riverbanks typically requires both a high sediment supply (so, a substantial region of eroding mountains in the river’s drainage basin) and a moderate slope (low enough to allow for deposition, high enough to keep the water flow fast). An inconsistent water supply helps as well, such that the river frequently floods over bars. Thus, the ideal situation is a large river running off the foothills of a mountain range, mostly fed by seasonal meltwater from glaciers. But braided rivers are also common in arid regions where there is little vegetation to stabilize the riverbank, windblown sediment often deposits in the riverbed, and storms or wet seasons may cause occasional flooding.

Examples: Brahmaputra (India/Bangladesh), Platte (US), Tagliamento (Italy)

Dimensions: The Brahmaputra has subchannels 100-3 km wide within a larger channel 10-20 km wide, and falls 120 m over its ~850 km course. Most braided rivers are much smaller, with channels under 1 km wide and subchannels as little as 10 m, and also steeper—typically at least 16 m fall per km of river. As stated, they’re usually quite shallow; the Brahmaputra is around 30 m deep on average, and smaller rivers can be less than 1 m deep while still quite broad.

Impact: These broad, shallow rivers that deposit out large amounts of sediment can make for fairly lush wetlands. They can sometimes also make for good farmland, though their instability makes settlement and construction directly on the bank difficult, and they’re also often too shallow for regular river travel. Their breadth also makes bridges difficult to construct, though they can be relatively easy to ford. In modern times, many formerly braided rivers have been artificially confined into regular courses.

Alluvial Fan

|

| Alluvial fan in Death Valley, California (with a road over it). Marli Miller, University of Oregon |

A depositional feature that forms when a river’s gradient very suddenly decreases, such as when a river passes directly from a steep mountain channel to a flat plain; you can think of it as the extreme case for a braided river. The sediment in the water is immediately deposited at the point of this transition and then washed out onto the surrounding landscape, forming a conical mound. The surface is covered in small braided streams, which tend to rejoin in a single river at the perimeter of the fan.

Adjacent fans along the side of a ridgeline may eventually combine to form a continuous slope of sediment called a bajada.

|

| Death Valley, California. Modified from Dicklyon, Wikimedia |

Dimensions: Fans can be as little as a few meters wide to over 100 km, with slopes of 1-25°. They tend to be larger in arid regions, where there is little erosion.

Impact: These fans can provide a more convenient route up a steep slope or cliff, but are also prone to flash flooding.

Meandering River

|

| Jurua River, Brazil. Alexander Gerst, Wikimedia |

The typical form of major rivers once they have reached nearly flat ground, or for some other reason the rate of erosion on the riverbanks is low. Like braided rivers they deposit more sediment than they erode away, but erode more on the outside bank where they curve while depositing more on the inside bank. But the slower-moving water erodes slower at the banks, so that the river’s lateral migration is slower and it can settle into a single channel (vegetation growth on the banks also helps slow erosion; there were likely far fewer meandering rivers and more braided rivers before land plants evolved and braided rivers are still more common in arid regions). As such, the channels are deeper and the formation of anabranches rarer.

But curves do still tend to deepen over time, such that the river loops back and forth along its course. These loops broaden over time, such that eventually two neighboring loops will breach the bar between them, forming a shortcut past the loop between them on the other side of the river. That loop will eventually be abandoned, but the deepest section on the outside edge of the curve can survive for some time as an oxbow lake, fed only by rain in its immediate surroundings, until it eventually fills in with sediment.

The transition from braided to meandering rivers isn't instantaneous though: in between are sinuous rivers that mostly follow one course and gently meander, but still tend to form many short-lived anabranches and river islands.

| I couldn't find this diagram in English but I think it communicates the point well: as rivers flatten out, they'll tend to branch less and meander more. Antonov, Wikimedia |

A meandering river is usually the lowest part of a river, terminating at an estuary or river delta, but we’ll leave discussion of those to the Coastal category.

Examples: Mississippi (US), Amazon (Brazil), Yellow (China)

Dimensions: Meanders on the Mississippi River reach about 10 km from the center of the river’s course, and the river itself is 1-2 km wide—other rivers vary from under 100 m to over 10 km wide, with wider rivers tending to have less pronounced meanders relative to their size. Exactly when a river transitions from a braided river to a meandering river comes down to a complex balance of the sediment load in the river, the clast size of those sediments, and the presence of vegetation or other factors controlling erosion on the banks.

Impact: Much as with braided rivers, the sediment deposited on the banks can make for lush wetlands or fertile farmland. But the more stable banks and water level make settlement and construction easier. They are still prone to occasional flooding, though, and if anything these floods can be more hazardous for how infrequent they are and thus how unprepared the victims tend to be.

River Island

|

| Islands in the Zambezi River, Zambia/Zimbabwe. Diego Delso, Wikimedia |

Dimensions: How large river islands get depends on how you define them; Bananal Island in Brazil is 350 km long and 55 km wide, but so vast compared to the bounding channels that you might not consider it to be an island within a river so much as a region of land between anabranches so distant they might be called separate rivers. Less ambiguous river islands are more typically 100 m to 10 km long and 1/10 as wide.

Impact: River islands tend to be favored as sites for new towns or cities as they tend to allow for easier crossing of the river, are easy to defend, and have more waterfront. Many old cities today have heavily populated river islands at their cores, and many have formed new ones by building canals.

Floodplain

|

| Zambezi River Floodplain, Zambia. NASA |

A flat area between the banks of some rivers and moderately

steeper valley walls. In wet periods, the water level rises and the river

overflows its banks, flooding the plain. The water slows and so deposits

sediments across the plain. The largest clasts are deposited on the channel

banks, forming natural levees that

help keep the river in its channel in dry periods and reinforces the

periodicity of the flooding. Tributary streams may need to flow alongside the

river for some time before crossing a breach in the levee, in which case they

are delightfully called yazoo streams. The plain outside the levees is

generally fairly flat and level, and there may be flat terraces further up the valley walls; remnants of previous plains

when the valley was shallower. Shallow hollows in the plains may retain

standing water after flooding, forming a back swamp.

|

| Source |

Some rivers flood every year—typically if the river’s drainage basin has a dry and wet season, or includes mountains that accumulate ice in winter and thaw in spring—sometimes regularly enough to set a calendar to. Others flood less frequently, but their meanders will usually remain within the floodplain.

Examples: Nile floodplain (Egypt), Yellow River floodplain (China), Pantanal (Brazil/Paraguay)

Dimensions: The Nile floodplain is about 20 km across over much of its course. Other flood plains can be hundreds of kilometers across. At the lower end, small streams may regularly flood an area meters from their banks, called flood-meadows.

Impact: In wet climates, floodplains may form broad wetlands; in drier areas, they can form lush areas even with no precipitation. They are among the most fertile regions on the planet, and make for excellent farmland. Most of the earliest civilizations started in flood plains, and they have remained major agricultural regions. Much of ancient Egypt’s success can be attributed to the reliability of the Nile’s floods and subsequent crop harvests. But in wetter regions the flooding can be more variable. Given that large population centers tend to form in these regions, an unusually high flood can cause catastrophic damage and death—though these floods are too infrequent and the land too productive to dissuade recolonization of the devastated areas.

Lake

|

| Lake Tahoe, USA. Michael, Wikimedia |

A lake forms where there is an enclosed basin with a bottom lower than any point on the perimeter. The basin fills until the water level reaches the lowest point on the perimeter, where water then flows out into a new river (our “all points on land have a downhill path to the sea” rule for fluvial terrain holds here only if the path passes along the water surface, not the lakebed). This basin is typically formed by tectonic action (opening of basin by tectonic extension and subsidence or blocking of an outlet by compression and uplift) or glacial erosion (which we’ll discuss later), but small lakes can also be formed by volcanic activity, impact craters, landslides, eolian action (again, we’ll discuss it later), waterfalls (the aforementioned plunge pools), fluvial deposition of sediment (formation of oxbow lakes, formation of levees in floodplains), deposition of sediment along coasts by wave or tide action (again, later), biological activity (beaver dams, peat deposition, coral formation), or human activity (damming rivers to make reservoirs or excavating out quarries and then abandoning them).

As mentioned, the lake will fill with sediment and the outlet channel will erode down, so all lakes will eventually either be filled in or drain out their lowering outlet. But this can take thousands or even millions of years, especially if there is continued tectonism, the lake is fed by a small or arid drainage basin, or the lake is partircularly large. Filling of lakes with sediment can make flat, fertile plains in highland regions, and for a time these may still occasionally flood in wet periods.

Young mountain ranges tend to form many lakes, especially in interior plateaus. Flat, tectonically inactive plains rarely form large lakes, except after the retreat of major glaciers. And as we’ll see, more arid regions can form more enduring lakes within endorheic basins.

Many simple map generators will depict lakes only where the land surface is below sea level, but in truth lakes may form kilometers higher, and a fair portion of them do not reach below sea level even at their deepest point, such that they wouldn’t appear on such maps at all. Some people will try to draw their own lakes on such maps, but a common error is to draw them such that the elevation of their shores vary, which shouldn’t be possible for a flat lake surface. On the other hand, some lakes within endorheic basins may have surfaces below sea level, but we’ll discuss those later.

The general appearance of lakes varies, of course, but notably artificial reservoirs often have very jagged coastlines because they formed only recently and their coastlines lie along existing topography; some lakes at high latitudes appear similar due to continuously changing water level after the recent retreat of large glaciers. But more mature lakes will often have more rounded coastlines due to erosion and deposition along their shores.

Examples: Lake Superior (US/Canada), Lake Baikal (Russia), Lake Tanganyika (Southeast Africa).

Dimensions: The Caspian Sea is over 370,000 km2 and 1200 km long, but is not so much a lake that formed on the continents as a small section of ocean that has been trapped between pieces of continent during the assembly of Eurasia. Lake Superior is the largest freshwater lake by area, at over 82,000 km2 and about 600 km long, but is caused primarly by glacial erosion. The largest freshwater lake by area formed on land by primarily nonglacial forces is Lake Tanganyika, at over 32,000 km2 and 670 km long. Otherwise lakes come in all shapes and sizes, with relatively few over 300 km long or 5,000 km2 in area. Lake Baikal reaches to 1,627 m depth, but most lakes are under 100 m deep.

Impact: Lakes tend to have calmer, slower-moving water than rivers, so may make better environments for plant life, slow-swimming or young animals, or small boats and rafts. They can also make for convenient water sources, especially in arid regions where arroyos may run dry but lakes may be more persistent—though in such cases, lake level may vary considerably with the seasons, making plant growth and permanent settlement on the banks difficult.

Large lakes, however, can develop large waves or currents, and may even develop their own weather systems. A particular large lake can be treated in some ways as a small sea, inhabited by large marine animals, supporting large fishing communities or crossed with significant watercraft, and in some cases hosting major naval battles.

Wetlands

|

| Warta Mouth National Park, Poland. A. Savin, Wikimedia |

Areas that typically have standing or slow-moving water, forming unique ecosystems. Marshes and swamps occur on the banks of meandering rivers and lakes; marshes are the shallow water regions that grow reeds and other low plants, and swamps are the adjoining flat areas that are above water but still fairly wet and may occasionally flood, and grow larger trees and undergrowth.

|

| USGS |

Examples: Everglades (US), Mesopotamian Marshes (Iraq), Vasyugan Swamp (Russia)

Dimensions: Anywhere from small pockets on the bank of a stream to hundreds of thousands of km2 in a major river floodplain.

Impact: Wetlands can support a large diversity of wildlife species. Often animals from neighboring ecosystems spend a childhood stage in marshes or swamps, sheltered from large predators. Their suitability as farmland varies; some can be quite fertile, but others may be too salty or acidic. But even in the former case, clearing them for the first time can be a challenge, and cause significant ecological damage, as well as destabilize rivers and lead to flooding. The peat from bogs and fens has also been an important heating fuel through much of history for cold regions, and they also produce other resources like bog iron.

Wetlands are also notoriously difficult to traverse. A relatively small river can become a more significant barrier through the wetlands it produces, and so paths through these wetlands can be strategic chokepoints.

Karst

|

| Ha Long Bay, Vietnam. Thomas Hirsch, Wikimedia |

A type of terrain that can form where the bedrock is easily-eroded limestone—formed in warm, shallow marine environments—or a similar material. Rather than eroding down evenly from the surface, these areas tend to erode much more quickly at faults and cracks in the rock and so form complex surfaces and underground cave systems. Rivers may disappear into a cave and then reappear elsewhere downhill as a spring, sometimes several times. As such our “rule” that there must be a downhill path to the sea from all points still sort of holds, but the path may sometimes pass underground, which won’t be clear from a topographic map.

|

| Common karst features. USGS |

The bare limestone often has a distinctive “knobby” appearance, becoming more jagged as it is more deeply eroded. Where they don’t disappear into caves, rivers may cut deep gorges (called calanques in the Mediterranean). After most of the limestone is eroded away, isolated towers of limestone can remain with steep cliffs; much like the succession of canyons to badlands in uplifted plains (both are caused by uneven erosion, but in karst regions it’s more fundamentally tied to the properties of the rock, so these structures can form in much wetter climates). In the most dramatic cases, this creates a terrain covered in tall, sharp blades or pillars of rock. But in most karst regions the limestone is at least partially buried in sediment, such that only outcrops are visible; making for still hilly and irregular but not ludicrously impassable terrain.

Though karst can appear essentially anywhere (the limestone need not have been deposited recently), the most exposed and dramatic examples tend to appear in warm, wet climates with heavier erosion. Some amount of recent uplift is also necessary for the limestone to have been exposed at the surface but not yet totally eroded away or buried.

Examples: South China Karst, Ha Long Bay (Vietnam), Tsingy de Bemaraha (Madagascar), Massif Central (France)

Dimensions: Definitions vary, but roughly 15% of Earth’s land surface is some variety of karst terrain—though again, most of this has only outcroppings of bare limestone. Where they do appear, uncovered limestone pillars can be up to hundreds of meters tall, even while only a fraction as wide at their base and with near-vertical sides.

Impact: Like badlands regions, karst areas are ideal for defense against invading forces. Heavily eroded karst can be difficult and hazardous to traverse, to the point of restricting travel. And of course, river travel can be difficult if rivers occasionally disappear underground.

Cave

.jpg) |

| Skocjan Caves, Slovenia. Peretz Partensky, Wikimedia |

I’ve already discussed lava tubes in the past, and volcanic magma chambers can also form caves once they go extinct, but most caves today form in karst regions, as water running underground dissolves the surrounding limestone. Caves can also form by dissolution of other minerals (evaporites like salt and gypsum especially), wave and tidal erosion along coastlines, or opening of gaps in tectonic faults.

Some caves can have large openings to the surface, and others can be completely isolated. Because they often form—or are expanded by—erosion along underground streams, they often have complex branching patterns, and large chambers may occasionally be connected by tiny passageways. Slow erosion and deposition of minerals within caves can form a variety of unique structures like stalactites and stalagmites, especially in karst caves.

Examples: Mammoth Cave (US), Clearwater Cave System (Malaysia), Son Doong Cave (Vietnam)

Dimensions: The largest cave systems contain 100s of km of passages and can reach km deep, though each passage is no more thans 100s of m across. The longest known completely underground room in a cave (Sarawak Chamber) is 700 m long, but open-ended passages near the surface can run for kilometers.

Much as with lava tubes, there is likely to be some inverse relationship between cave size and surface gravity, as the ultimate limit on the maximum size of caves is the ability for the walls to support the ceiling against the pressure of overlying rock. This also means, incidentally, that the maximum size of a cave decreases with depth, and we’re unlikely to find any in the lower crust or mantle.

Impact: Caves provide shelter from the elements, and so any reasonably accessible cave will tend to be inhabited by animals, including early humans. The caves will also tend to preserve anything left inside them, hence the many pieces of ancient artifacts, artwork, or remains found in caves. More recently, they have continued to serve as temporary shelter, secret hideaways, or makeshift homes. Cave exploration has become something of sport in recent years, with teams exploring deep into thin passageways, though personally I can think of few things I wouldn’t rather experience.

Caves isolated from the surface can occasionally form isolated ecosystems, usually supported by chemotrophic microbes and including various animal species adapted for life without access to light.

Glacial

|

| Aare Glaciers, Switzerland. Markus Bernet, Wikimedia |

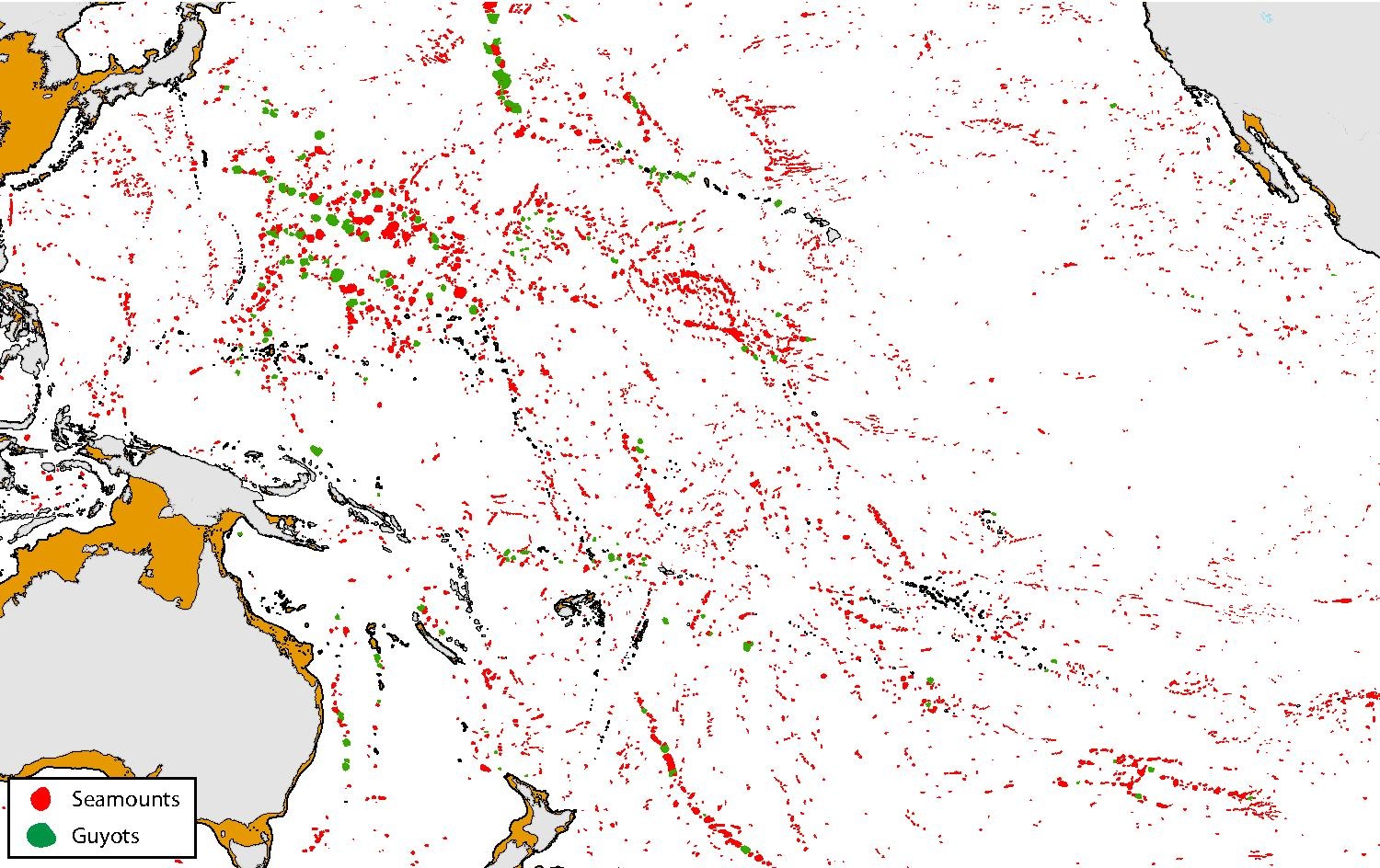

Terrain dominated by the action of large masses of ice, either currently or in the geologically recent past. This, of course, requires that glaciers will be present, which isn’t a given for Earthlike worlds, and many of the features we’ll discuss here result from the recent retreat of major glaciers, and so might be expected on a world in the warm stage of an ice age cycling between warmer and cooler states—i.e., worlds like Earth today. If your world is not in an ice age, it will simply lack many of these features, though it may still have some mountain glaciers.

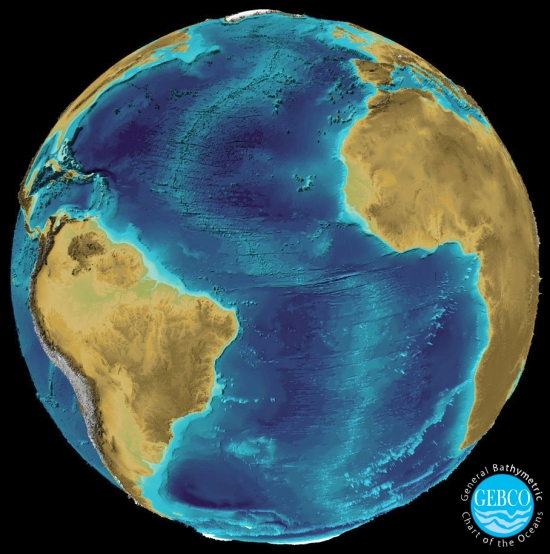

Glaciers are masses of ice so large (roughly 50 meters deep at least, probably scaling inversely with gravity on other worlds) that the ice near the base is continuously deformed by the pressure, and the whole mass begins to flow outwards like a very viscous fluid—though, much like the mantle, it’s still mostly solid throughout. If it’s not too cold, the pressure at the glacier’s base may form a thin layer of water that allows the glacier to slide along much faster, but even without this the glacier will continue to flow through deformation of the solid ice alone.

The position and extent of a glacier isn’t merely a matter of temperature: it’s largely a balance between the addition of ice, mostly by snowfall in winter, and loss of ice, mostly by melting in summer, but also by calving of icebergs where a glacier meets the sea. Obviously the colder it is, the less a glacier will melt, and it also has to remain below freezing for snow to fall, but the region with the greatest overall snowfall compared to melting may be far from the coldest region of the planet, and so major glaciers may form far from the poles; the Laurentide Ice Sheet that covered much of North America 20,000 years ago probably first formed in Quebec or Labrador.

A large glacier can then extend out into regions that receive little snow and remain above-freezing year-round, so long as the influx of ice from the colder parts of the glacier matches melting at the glacier surface. As this balance shifts—both across the seasons and over long periods of time as climate shifts—the edge of the glacier will advance or retreat. But even when a glacier retreats, the ice within a glacier is still flowing outwards, towards the edges; it’s just that melting outpaces the flow of ice.

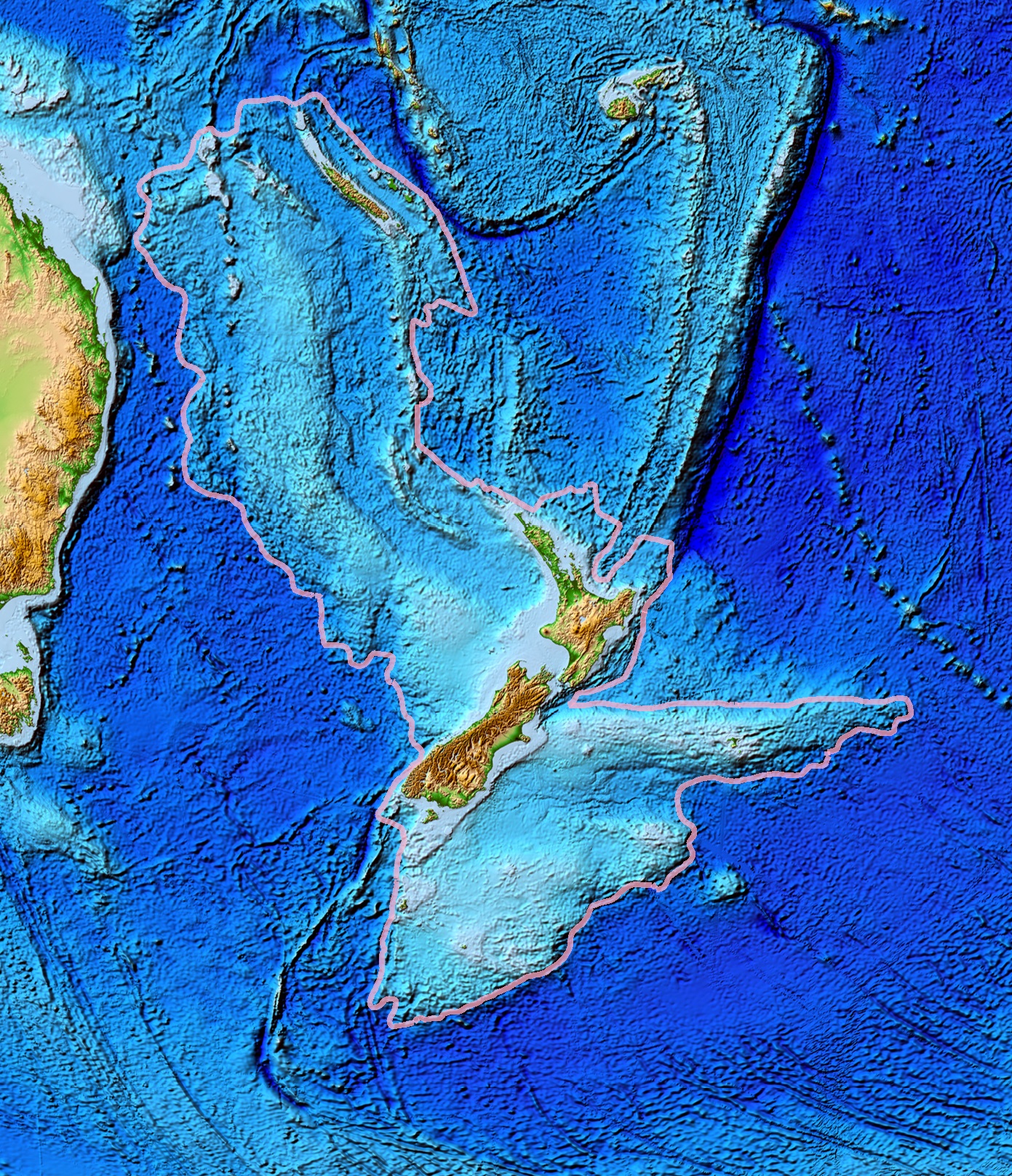

As the glacier advances, material eroded off the terrain below or falling on top of the glacier will be carried within it, and often pushed towards the end by the internal flow of ice (breaking down further in the process). As the glacier retreats, this material deposits out as glacial till: a mix of clasts of different sizes, from fine silt up to large boulders, often of various different rocks and minerals, with no internal sorting or layering—in contrast to the typically orderly deposits formed by purely fluvial erosion.

One common consequence of the advance and retreat of large glaciers is isostatic rebound. The weight of a large glacier can push down the land surface by as much as hundreds of meters; after the glacier retreats, the land gradually rises back up. In some areas of northern Europe and North America, the land is still rising after the retreat of the last glaciers, by as much as 2 centimers a year. This initial decline and then rise in terrain can pretty significantly shift drainage patterns over the region.

|

| Topography of Antarctica under the ice today (left) and a reconstruction of its topography after isostatic rebound (right). Paxman et al. 2019 |

We’ll discuss the major types of glaciers first, and then the landforms they create; most of these are, again, left in the wake of retreating glaciers, so the degree to which they’re present on your world will depend on its climatological history.

Mountain Glacier

|

| Morse and Muir Glaciers, Alaska. LCGS Russ, Wikimedia |

A.K.A. Alpine glacier. The most common type of glacier, forming within river and stream valleys in high mountains. Much as with rivers, they’ll flow downhill through channels, converge to join into larger glaciers, and generally follow all the same “rules” for rivers we established in the last section. If they terminate before reaching the sea, the meltwater they produce will typically form a stream; many major rivers are largely fed by glacial meltwater.

|

| Common glacial features. Kelvinsong, Wikimedia |

Though they often appear mostly white, large amounts of debris falling off the adjacent mountains may gather on top or be pulled into the glacier. As the glacier melts, this till will become concentrated within the ice, staining it black or brown. A glacier that has melted nearly completely may leave behind a rock glacier, now mostly composed of rock and sediment gathered around an icy core that still flows downhill.

|

| Chugach Mountains, Alaska. USGS |

As most glaciers have retreated since their maximum extent thousands of years ago, those that don’t reach the sea mostly terminate within the valleys they themselves have carved out, forming sloping cliffs of rock between the valley walls, with meltwater forming either a lake or a stream (the latter often running out a tunnel in the ice that extends under the glacier a short distance). But a few Piedmont glaciers extend out from the mountains into flatter ground and spread out into a sloped fan of ice.

.jpg/1024px-Bylot_Island_Glacier_(cropped).jpg) |

| Bylot Island, Canada. Mike Beauregard, Wikimedia |

Examples: Aletsch Glacier (Switzerland), Endeavor Piedmont Glacier (Antarctica), Eel Glacier (US), Fedchenko Glacier (Tajikistan)

Dimensions: Typically 100s of m deep and similarly wide, and km long. The longest glaciers outside the polar regions run around 70 km long, and they can run to several km deep.

Impact: Though flat on top, traversing a glacier can be quite dangerous, as they’re often cut through with crevasses reaching deep into the glacier that may be concealed under snow or debris. Continuous flow of the ice also makes permanent construction largely impossible.

Continental Glacier

|

| Greenland. Hannes Grobe, Wikimedia |

A.K.A. Ice sheet. Large glaciers up to kilometers deep, covering large portions of major landmasses. These spread outward in all directions from the deepest point at their center, largely ignoring topography and simply flowing over any but the tallest mountains. Though if the glacier does meet a high mountain range near its edges, it may divide into many mountain glaciers passing between the highest peaks (and possibly merge on the other side, like a stream passing through a grate).

Major glaciers spread across much of North America and Eurasia in the glacial periods of our current ice ages, and many of the unique features of those regions is a result of their erosion.

|

| Major glaciers in the northern hemisphere during the last glacial maximum. Hannes Grobe, Wikimedia |

The majority of Earth’s fresh water is locked in these glaciers. Were they to melt completely, sea level would rise by about 70 meters, though even in the worst climate change scenarios this would probably take thousands of years. 20,000 years ago, in the depths of the most recent glacial period, sea level was about 120 meters lower than today.

Only two ice sheets greater than 50,000 km2 in area remain on Earth today, in Antarctica and Greenland, both covering essentially their entire landmass (for now). But various smaller ice caps (with high central domes above the surrounding terrain) and icefields (lower than their confining mountains but still deep, contiguous, and flowing out in all directions) exist as well. They behave in many ways like ice sheets, though are generally confined within mountains and extend past them only in individual tongues that behave as mountain glaciers (called outlet glaciers).

|

| NASA |

Mars also has a pair of polar ice sheets (and various smaller glaciers), which are in many ways similar to Earth’s, but because they are far older and receive little precipitation, they have some different features; in particular, patterns of spiraling grooves formed by gradual erosion and deposition of soil by winds over millions of years.

Examples: Antarctic Ice Sheet; Greenland Ice Sheet. Vatnajökull (Iceland) is a notable ice cap, and the Southern Patagonian Icefield (Chile/Argentina) a notable icefield.

Dimensions: The Antarctic Ice Sheet covers 14 million km2 and reaches to over 4 km deep. Even larger glaciers cover the northern continents during glacial periods. These glaciers typically have parabolic slopes: close to flat near the center, then gradually curving down to their fairly steep edges, which may be shear cliffs of ice. But the exact shape can be fairly complex due to varying rates of ice flow across different types of underlying terrain.

Impact: Continental Glaciers are not completely lifeless—some microbes can survive in the ice, and emperor penguins famously overwinter on the Antarctic Ice Sheet—but they are significantly less hospitable than even the coldest tundras. Aside from a few small science stations on more stable sections of the ice, they are also largely uninhabited by humans. Though they play an important role in balancing the climate and we certainly shouldn’t be happy to see them go, they’re about the most desolate and inhospitable regions of the Earth’s surface.

Ice Shelf

|

| Riiser-Larsen Ice Shelf, Antarctica. NASA |

A large expanse of ice floating on water, formed where a glacier encounters the sea. A deep glacier may still run along the land surface even when it is below sea level, because it is too heavy to be supported by the shallow coastal waters—this is the case across much of Antarctica. But eventually the glacier will run into deep-enough water that it can float. Without firm support at its base, the glacier thins out and becomes much flatter.

Icebergs will calve off the edges of the shelf, often leaving sheer cliffs at the edges, especially in summer. Thinner pack ice may gather along the edge of the ice shelf, forming a lower surface that amphibious animals can climb on to.

Dimensions: The Antarctic ice shelves total over 1.5 million km2 in area, and grow considerably in winter (for now). The permanent regions of ice are generally 100 m to 1 km thick; notably far thicker than sea ice that forms on its own in the open ocean, which is rarely more than a few meters thick.

Impact: Though the surfaces of these shelfs are similarly inhospitable to ice sheets, marine life can flourish in the shallow waters at the edge of the ice shelf. Various animals have adapted to swim and hunt in these waters and then climb onto the ice to rest or escape predators.

U-Shaped Valley

|

| Yosemite Valley, California. Tuxyso, Wikimedia |

A.K.A. Trough valley. The typical result of erosion by mountain glaciers. The glacier itself occupies far more space than a river stream typically does, often approaching the peaks of the surrounding mountains, so rather than digging a thin, deep channel, it carves out the whole valley floor. After the glacier retreats, the remaining valley tends to have a much broader, flatter floor than usual v-shaped valleys, bounded by very steep, sometimes near-vertical valley walls. A small stream will typically run through the center, often called a misfit stream as it’s far smaller than what would usually be expected for such a large valley.

|

| Cecilia Bernal, Wikimedia |

There are numerous specific features formed by U-shaped valleys, many with their own fancy French names, so let’s run through them quickly:

- Arête:

The sharp ridgeline between neighboring U-shaped valleys, with even steeper

slopes than those between v-shaped valleys.

.jpg/640px-Schaefler_to_Saentis_(_West).jpg)

Alpstein, Switzerland. Caumasee, Wikimedia - Cirque:

A basin scooped out of the side of a mountain formed at the head of a glacier

(the term may also refer to a small glacier on a slope that scoops out such a

basin). If the glacier reaches to flatter ground, the descending ice will often

erode out a depression there before proceeding into a U-shaped valley, such

that after the glacier melts a lake will form at the cirque’s base, called a tarn.

DooFi, Wikimedia - Glacial

Horn: A particular steep mountain peak formed where three or more cirques

form around the peak of a single mountain.

Alpamayo, Peru. Frank R 1981, Wikimedia - Col:

A broad term for the lowest point on a ridgeline between two peaks, but glacial

circues in particular tend to cut low cols between them when forming close

together on either side of an arête.

- Hanging Valley: A junction between

U-shaped valleys with floors at different elevations, such that there is a

steep cliff between them. This is formed where a tributary glacier joins a

larger glacier; so long as the tops of the glaciers are at similar levels,

there’s no strong tendency for them to erode their bases to similar levels.

There will often be a waterfall here from a misfit stream.

Bridalveil Fall, California. Mav, Wikimedia

Dimensions: Naturally, about as big as mountain glaciers, though they can be longer if formed by the longer glaciers that existed in the past; 100s of m to km wide with similarly tall walls, and up to 100s of km long.

Impact: The flat valley floor can make for good farmland or pasture in otherwise cold regions, and also make U-shaped valleys rather easier to move through than v-shaped valleys; but the dividing arêtes can make travel between valleys difficult, such that communities in these valleys may be fairly isolated and have better communication with distant regions in the same valley than with closer regions across ridgelines. Older valleys or those in lower terrain may have much gentler walls that don’t inhibit travel as much, but the valley floor will still generally be easier for travel and settlement.

If the glacier is still present upvalley, there is some risk that it will advance again and overrun any settlements in the valley. Alternatively, a hot summer may cause flash flooding, or a warming climate may melt the glacier completely and deny the valley its regular source of water.

Fjord

.jpg/1280px-Geiranger_Fjord_(7793986108).jpg) |

| Geiranger Fjord, Norway. Vladislov Bezrukov, Wikimedia |

A long inlet formed along mountainous coasts where a glacier has carved a U-shaped valley all the way out the sea, and then later warming of the climate has caused the glacier to retreat and sea level to rise and flood into the valley. The shores of the fjord will be steep along most of the fjord’s length, but at the end of the fjord the flat valley floor will form a shallow beach.

Examine the mountains along the west coast of the Americas, and you can see a gradual transition from typical mountain coasts with forearc basins, to mountains directly abutting the coast with occasional lone fjords, to coastal archipelagos of mountainous islands separated by intersecting fjords (the sea has flooded over the cols between neighboring valleys).

In some cases a glacier may carve out a deep valley floor, but with high ground remaining between it and the sea; in this case a finger lake may form, broadly similar to a fjord but not directly connected to the sea, instead draining out into a thin river at one end. Sometimes there may be a fjord and finger lake(s) in the same valley.

Examples: Sognefjord (Norway), Scoresby Sound (Greenland), Saguenay Fjord (Canada). The Finger Lakes (US) are prominent, well, finger lakes.

Dimension: Again, as big as glacial valleys, with waters sometimes over a km deep.

Impact: Again, the valley above the fjord can make for good farming, and the fjord itself can make for good fishing; the sheltered waters are ideal breeding grounds. A coastal town at the end of a fjord can take advantage of both resources. Because of the high ridgelines and steep coasts closer to the sea, travel between neighboring fjords requires either a long detour inland or travel by boat, so it’s perhaps no surprise that the inhabitants of Norway developped a maritime culture.

Moraine

|

| Lateral moraine of Miage Glacier, Italy. Yves Lemarcheix, Wikimedia |

Long mounds of eroded material gathered along the edges of a glacier. Terminal moraines are pushed along the forward “tongue” of the glacier, lateral moraines gather along the edges of a mountain glacier, and where two mountain glaciers meet their lateral moraines may join into a medial moraine between them.

When a glacier retreats, the material remains and forms a mound of glacial till on the ground (which is still called a “moraine”). A lake often forms from meltwater gathering behind the terminal moraine. A retreating mountain glacier may leave many moraines in its wake during brief episodes of advance, forming a series of lakes, called paternoster lakes, connected by a single stream (this can also form finger lakes in valleys with shallower gradients).

|

| Seven Rila Lakes, Bulgaria. Ivelin Minkov, Wikimedia |

Examples: Oak Ridges Moraine (Canada), Cape Cod (US); Long Island (US) is formed of two terminal moraines.

Dimensions: The largest moraines left by continental glaciers can stretch 1,000s of km and pile up 100s of m high, though if they’ve had any significant time to erode they’ll tend to have fairly shallow slopes. Moraines in mountains are more typicall 10s of m high at most, and soon erode down to very moderate hills.

Impact: These generally aren’t high or steep enough to impede travel, and are notable mostly just for the way they shape hydrology, forming lakes or dividing drainage basins. If a large moraine forms near the coast and sea level later rises, it may form a string of peninsulas, islands, and shallow banks, as can be seen in the US northeast.

Outwash Plain

|

| Skeiðarársandur, Iceland. TommyBee, Wikimedia |

A.K.A. sandur. The region directly in front of a glacier, dominated by the flow of meltwater off the glacier. These streams will carry a good bit of glacial till, so often form braided streams and alluvial fans (technically “outwash fans”, as they contain unsorted till rather than the fine sediment of alluvial fans). Moraines and other deposits will form lakes here and there across the landscape. If the glacier is still nearby, cold air descending its slope will blow out across the plain as cold katabatic winds. These winds can carry dust 100s or even 1,000s of km from the glacier and deposit it as fine layers of fine, packed sediment called loess.

|

| Hans Hillewaert, Wikimedia |

As these plains often form on terrain the glacier has passed over, they’ll typically be fairly flat, with any protruding features rounded down by glacial erosion. There are numerous named landforms often left behind by retreating glaciers in their outwash plains, many of which may still be present long after the glacier’s retreat, so to save some time I’ll just review them here:

- Esker: A long, snaking mound of till, formed

by a meltwater stream running through a tunnel at the base of the glacier;

after the glacier retreats, the stream shifts to lower ground, but the till it had

deposited within the tunnel remains.

Fulufjället National Park, Sweden. Hanna Lokrantz, Wikimedia - Kame: An irregular hill, formed when till

gathers within a pit on top of a melting glacier and then deposits as the

glacier melts completely.

Dude Hill, Wyoming. Jo Suderman, NPS - Kettle Lake: A roundish, deep lake,

formed when a block of ice breaks from the glacier, settles into the ground,

and then later melts. The ice may be covered in sediment (forming a mound

called a pingo) and take thousands of years to melt, such that a mound

gradually subsides into a lake.

Isunngua, Greenland. Algkalv, Wikimedia - Drumlin: A tadpole-shaped mound with the

“tail” pointing in the direction of glacial flow. Exactly how they form is a

matter of debate, but it’s generally believed to be due to deposition of till beneath

a glacier (either deposited from meltwater, like an esker, or dragged along by

the ice) into a mound that is then carved into shape by further glacier flow.

Source - Roche

Moutonnée: A hill of bedrock with a smooth slope on one side, facing into

the direction of glacial flow, and a steep slope on the other side. The flow of

the glacier across the surface eroded out the smooth side, while plucking,

formation of ice within vertical fractures in the rock, pulled chunks of rock

away from the steep side.

Chabacano, Wikimedia - Crag

and Tail: A hill with exposed bedrock like a roche moutonnée (the crag),

but a long tail of sediment like a drumlin; in this case the rock was embedded

in sediment, and the glacier eroded away the sediment from one side, but the

tougher bedrock sheltered the sediment on its lee side.

Binny Craig, Scotland. paul birrell, Wikimedia - Erratic:

A large boulder standing on the ground, with no nearby exposed bedrock it may

have broken off from. These were carried within the glacier, and then deposited

when they melted.

Yorkshire, England. Gordon Hatton, Wikimedia

Examples: Hummocky terrain can be seen most prominently in Canada and Finland, and young outwash plains are present in many areas of Iceland.

Dimensions: Former outwash plains stretch for millions of km2. Individual eskers and kames are typically 1s to 10s of m high, drumlins and eroded hills generally a bit larger, up to over a km. Kettle lakes can be m to km across, and even larger lakes may form in the irregular basins formed.