An Apple Pie from Scratch, Part VIb: Climate: Biomes and Climate Zones

|

| Himalayas mountains, which cause a strong rainshadow effect. NASA |

Now that we’ve outlined the essential properties of our world’s global climate, it’s time to get into the particulars. For Earthlike worlds, the atmospheric convection cells should broadly determine the positions of major bands of climate—tropical, desert, temperate, tundra—but if we really want to get a sense of the weather, seasons, wildlife, and geology of a particular spot on the world—in essence, what it would be like to be there—then we have to start getting into how climate plays out locally.

This post will take some of the theory of climate we went

over last time (if you haven’t already, I strongly recommend reading at least

the first couple sections of the last post,

because they’re vital to understanding this one) and apply it as a practical

guide to mapping out the climate zones of a fictional world, with topography

and orbital features as a starting point. For this post, however, we’ll be

assuming fairly Earthlike worlds and using some tools only applicable to such

cases—that means worlds with insolation, year length, day length, obliquity,

eccentricity, size, volcanic activity, land area, pressure, and vegetation

broadly similar to Earth’s properties (about as similar as Teacup Ae is,

anyway). I will take time to address some of the more exotic cases in another

post, but let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

- Climate Zone Classification

- Step 1: Basic Sketch

- Step 2: Simulating Temperature

- Step 3: Ocean Currents and Mountains

- Step 4: Climate Bands

- Step 5: Winds

- Step 6: Precipitation

- Step 7: Climate Zones

- Impacts of Climate

- A: Tropical Climates

- B: Arid Climates

- C: Temperate Climates

- D: Continental Climates

- E: Polar and Alpine Climate

- Biomes and Biogeographic Regions

- In Summary

- Notes

Climate Zone Classification

There are, of course, many variations in local climate on

Earth, and possibly even more on other worlds, but generally speaking we can

split Earth’s surface into a handful of zones with fairly similar climate, and

so fairly similar weather and wildlife.

Now, many people tend to use “biome” and “climate zone” interchangeably

but that isn’t quite accurate. Biomes are regions with similar

ecosystems inhabited by similar organisms, and so are descriptive

regions; you have to mark them out based on the actual life present. Climate

zones are proscriptive; they’re determined by strict factors

resulting from global patterns, and so can be marked out based on a set of

rules (though we’ll have to use a bit of personal intuition here because of the

limited information and tools at hand). We can also distinguish between these

areas and biogeographic regions, which are contiguous areas with similar

enough climates and few enough barriers that wildlife can travel freely, such

that similar ecological niches tend to be occupied by related species.

Climate zones play a major role in determining biomes and

biogeographic regions, but they’re not the only factor; in the scheme we’ll

use, coastal New England and central Russia are within the same climate zone

even though they have rather different life inhabiting them. This tutorial

focuses on marking climate zones, but we’ll discuss biomes and biogeographic

regions a bit here and in following posts.

There are a variety of climate zone schemes used, but within

the worldbuilding community by far the most popular is the Köppen climate

classification system (A.K.A. the Köppen-Geiger system, as it’s a

modification of the original). This system is strictly determined by

temperature and precipitation during the warmest and coldest months (sometimes

few months) of the year, both of which can be at least guessed at based on

global climate patterns.

The Köppen system includes 31 climate zones broken down into

5 groups, but many of these climate zones are quite similar to each other or

appear only in very small regions. So to make things a bit easier, we’ll use a

reduced set of 14 climate zones.

At a glance, the impact of the atmospheric convection cells

is clear in the grouping of climate zones into horizontal belts: Lush

rainforests at the equator, giving way to savanna, steppe, and then hot deserts

at the horse latitudes, then temperate climate zones, then subarctic, and

finally the frigid tundra and ice caps.

It’s also pretty clear that topography has a big impact:

high plateaus like the Himalayas and Rockies create cold deserts and even

tundra zones far from the poles.

But there’s definitely more at play here: these climate

belts appear slanted across the continents, and some appear only on certain

sides; mediterranean and oceanic climate zones are mostly restricted to the

west coasts of continents, and subtropical zones to the east coasts.

That’s the subtle variation we want to reproduce here; not

only in pursuit of realism, but also to give our worlds a bit of diversity and

help guide the development of lifeforms and societies later on.

Before we start, I’m assuming you already have at least a

basic sketch of your world’s landmasses and topography. We don’t need anything

too detailed just yet. If you haven’t gotten that far, I’ll refer you back to

my guide to constructing a tectonic history. I suggest using an equirectangular

projection for the map, as it accurately represents cardinal directions

without distorting shapes too much; gplates can export such maps (it calls them

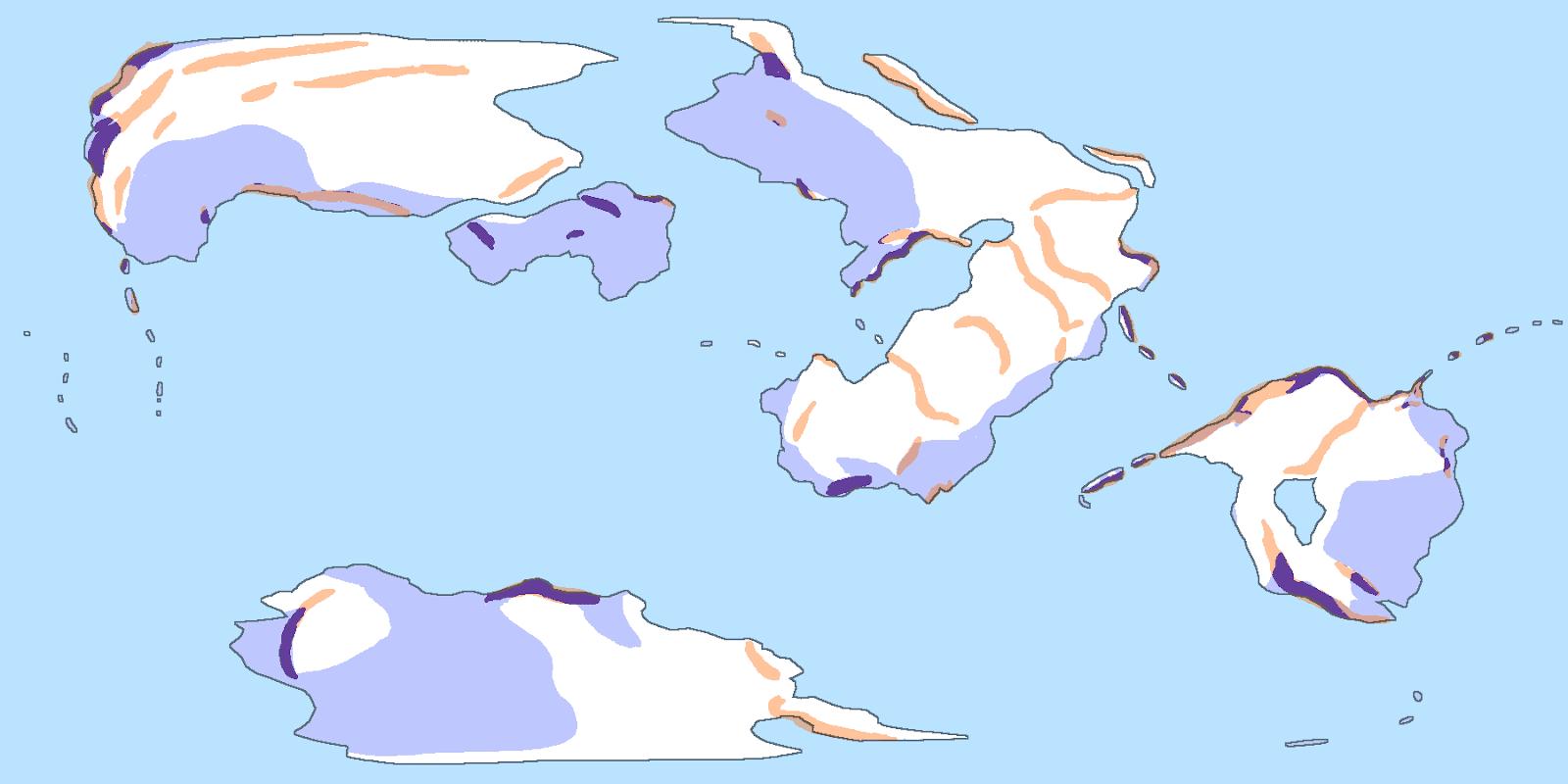

just “rectangular”). Here’s what I’m working with in the case of our example

world, Teacup Ae (with the interim names of the continents and oceans, for

reference):

However, east-west distances near the poles are pretty

distorted on this projection, so I suggest you have Gplates open as well in the

globe view, and use the measurement tool there when judging distances from the

coasts (Even if you didn’t build your world map in Gplates, you can import any

equirectangular map as a raster). Maptoglobe is also a

decent option.

I’m also assuming you’ve picked out the orbital parameters

that will determine your world’s seasonal cycle; obliquity, eccentricity,

and argument of obliquity. If you’re unfamiliar with the terms, I

defined them in Part III;

I’ve also discussed their impact on habitability

and global climate,

and built the “Irradiance Fast Rot” tab in my spreadsheet

to give you an idea of what impact particular parameters will have. I initially

defined these values for Teacup Ae as 15°

obliquity, 0.1 eccentricity, and 150° argument of obliquity, but in the course

of making this tutorial I’ve found the need to tweak them a bit to get results

I liked—so don’t be afraid to do the same yourself.

And finally, I will assume that these planets all spin

towards the east, as Earth does. If your planet spins west and you want

to avoid getting confused over the course of this tutorial, you can flip your

map horizontally or rotate it 180°,

proceed through the tutorial, and then flip or rotate the map back at the end

(if you don’t like the climate map at the end of this tutorial, flipping the

map is also a useful way to get a different climate without needing new

landmasses and topography).

Step 1: Basic Sketch

To start off with, we’re going to need at least a basic

sketch of some major types of land cover: Desert, ice cap, dense forest and

more open grassland and shrubland. These are, of course, determined by the

climate, so it may seem like a catch-22 to have to use them to work out the

climate, but this is only a sketch; it doesn’t have to be perfect, and if you

like you can iterate this process by taking the final climate map and using it

to start the process over, tedious though that may be.

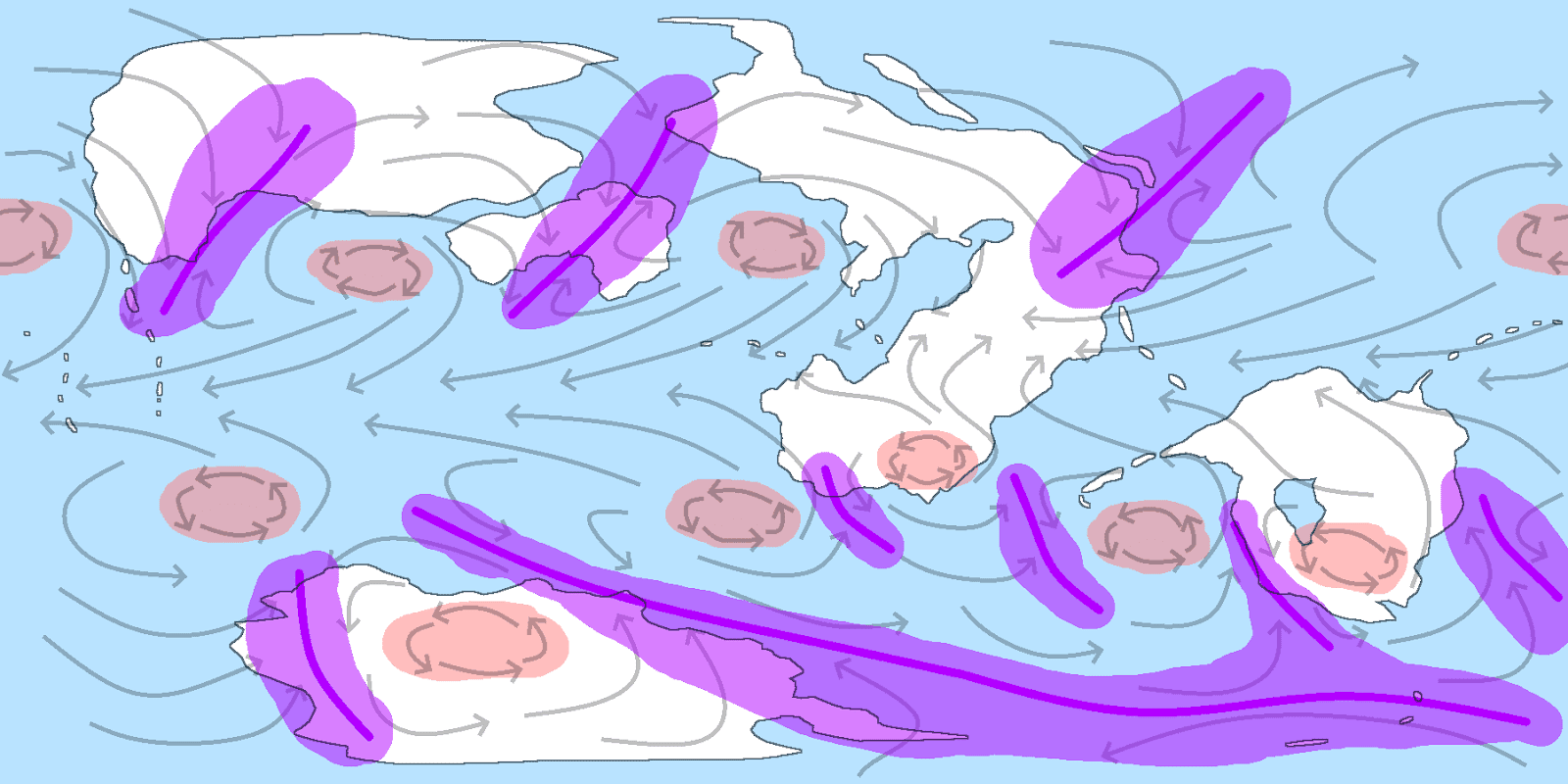

Prevailing Winds

To make our sketch, we’ll use the boundaries of the

atmospheric convection cells and the prevailing winds they produce. Though, as

we’ll see, these winds move with the seasons, in this case we’ll use a

simplified model where they’re tied to latitude, and we’ll also assume that

Teacup Ae’s rotation rate is similar enough to Earth’s for the cell boundaries

to be at roughly the same latitudes.

In that case, we can mark out alternating easterly and

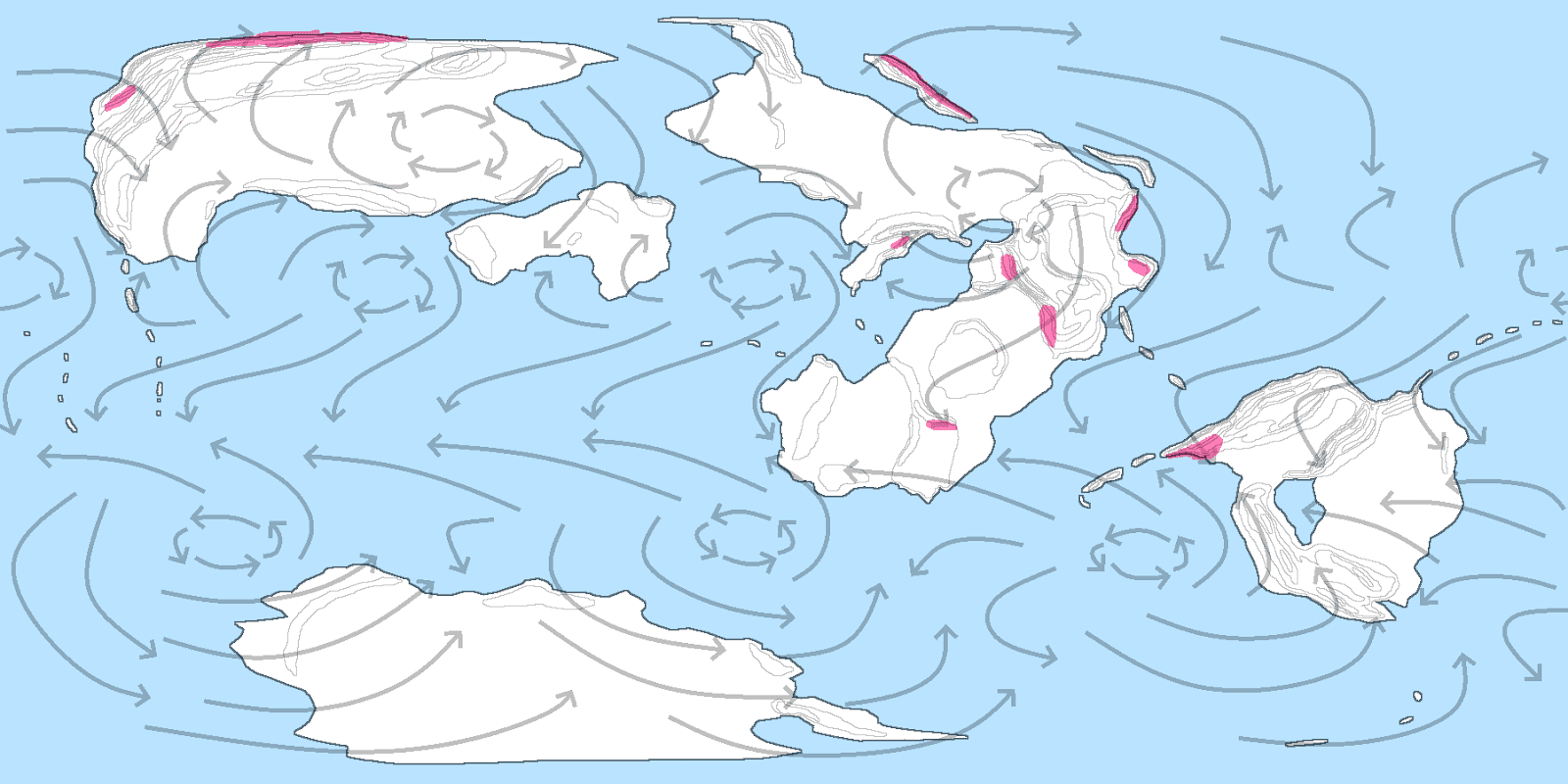

westerly prevailing winds like so:

As expected, we have converging winds at 0° and 60° latitude, which should create wet forest belts, and diverging winds at

30° and the poles, which should make dry desert belts and polar tundra. We also

have alternating easterly and westerly prevailing winds; onshore winds

blowing from sea to land will carry moisture far inland, while offshore

winds will leave the land relatively dry.

Ice Caps

Let’s mark out these

regions first, where ice persists year-round: Exactly how far they extend on

flat land depends on the particular global climate state—which is to say, you

can put the boundary about anywhere you want, but once it gets past around 40°

latitude you might be approaching the point where we’d expect a rapid

transition to a snowball state.

The ice caps will

extend further equatorward in mountains. The general rule of thumb is that 1

kilometer increased altitude is similar to moving 8° poleward, but distance

from the coasts matters as well; glaciers will advance further equatorward on

inland regions that are better insulated from the moderating influence of the

oceans. On the other hand, landmasses at the poles totally isolated from other

continents by oceans will be more likely to freeze over completely. These sorts

of differences in topography can lead to major asymmetries in the extent of ice

caps in either hemisphere.

So here’s how that

looks for Ae, with ice caps similar in size to Earth, though without isolated

landmasses like Antarctica or Greenland. Note that I’m only marking ice caps on

land here; they will extend onto the seas as well, but for this process we

don’t need to worry about that.

Deserts

Next up, desert regions which have little or no rain and

vegetation. The main belt of deserts will be near the horse latitudes, though

centered a little closer to the equator; on Earth they’re mostly between 15° and 30° latitude, but they’ll move with

widening or shrinking of the Hadley cell on other worlds.

They don’t occupy

all land at these latitudes, though; onshore winds keep east coasts at these

latitudes wet, reaching inwards around 1,000-1,500 km or to a substantial

mountain range. Monsoon winds can also bring moisture into the desert belt;

we’ll discuss the mechanisms behind them later, but for now suffice it to say

that large landmasses in the horse latitudes directly north or south of

equatorial oceans will tend to have wet coasts and smaller deserts.

Outside of the Hadley cell, winds are less regular so there

are no coastal deserts even where offshore winds occur. But deserts can still

occur here—or near the equator—out of reach of moist winds from the oceans.

One way is simple distance; air moving over land will be

continuously precipitating out water and so have less and less remaining as it

moves further inland, so forest and grassland gives way to steppe gives way to

desert. This should occur around 2-3,000 km away from coasts with onshore winds

and 1,000 km away from coasts with offshore winds (these distances may be

different on planets with different average levels of wind speed or

precipitation). Bear in mind that when I say “coasts” I’m referring to those on

major oceans, not every minor inlet or small inland sea.

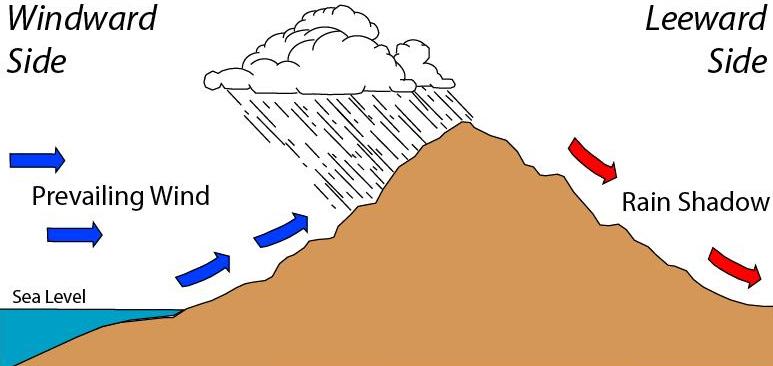

The other way is with orographic lift: When

water-laden air encounters a mountain range, it is forced upwards and the

surrounding pressure drops; the air thus expands and cools, and the water vapor

contained in it condenses and rains out. This means high rains on the windward

side of the mountains, but little moisture left for the leeward side, or

anywhere else downwind. The descending air also condenses and warms, creating a

hot, dry wind that further contributes to the leeward side’s aridity. Large

mountain ranges can thus create a rainshadow, with a sharp division

between lush upwind forests and bare downwind desert.

|

| Meg Stewart, Wikimedia |

Even fairly low mountains can cause orographic lift when

facing consistent winds,

but generally speaking it becomes significant at the scale of continents when

average relief, height of a mountain range about the surrounding

terrain, exceeds 1 km, and can create rainshadow deserts when relief exceeds 2

km. But in particular cases the impact can depend on the moisture content and

strength of the winds, which will depend on distance from the sea and the wider

context of atmospheric precipitation; a range on the equator facing onshore

winds may need to be over 3 km high to cause a rainshadow desert, while one far

inland at higher latitude may only need to be 1 km high.

On the windward side of the mountains, rains generally peak at

1-1.5 km relief, which can make these areas wetter than you might expect

without the mountains, in some cases even wetter than areas closer to the sea.

“Stepped” slopes with flat areas between sections of high relief can allow

moisture to reach higher altitudes, but in general you can expect anywhere

above 4 km to be dry.

All that in mind, here are Teacup Ae’s deserts:

Dense Forest

Much of the temperate areas of the planet will have some

amount of forest cover (assuming an Earthlike biosphere), but we’re more

concerned with rainforests and similarly lush coastal forests (this is because

what we’re ultimately concerned with in the next steps is albedo).

First off, there should be a belt of rainforest circling the

world within 10° latitude of the

equator. It won’t appear everywhere; regions at high altitude, thousands of

miles from the coasts, or affected by rainshadows will lack them. But anywhere

near the coasts, even with offshore winds, should sport thick forests. They

will tend to extend further poleward and inland on eastern coasts with onshore

winds, though.

Outside of this

rainforest belt, dense forests don’t encircle the world at any points, but do

still occur in areas with high rain. This will be mostly islands or coastlines

with onshore winds, especially those directly exposed to large oceans. You can particularly

expect large forested regions at about 45° to 60° latitude on western coasts.

We also have to

take orographic lift into account: Rainshadows will inhibit forest growth, but

high rains on the windward sides of mountains will encourage forests. A large

mountain range can create forests well inland of where you might normally

expect them (especially if it’s a young mountain range laden with nutrients).

And so here are

these various forest types on Ae:

Any remaining land we’ll

assume is scattered or less lush forest, shrubland, and grassland.

This process of

sketching out the climate can be pretty quick once you get used to it, so you

may find it useful on its own any time you’re not concerned with the

particulars of local climate. For example, this is how I produced those

paleoclimate maps in the last section. But for those of us looking for detail,

we can use this as a starting point for the next step.

Step 2: Simulating Temperature

For this step we’re going to use a convenient but remarkably

little-known piece of software called Clima-Sim

(the free “demo” version is sufficient for our uses). This program can do most

of the work for us of determining surface temperature across the seasons,

accounting for atmospheric circulation, insolation, surface albedo, and

topography. It even has basic modelling of clouds, ocean currents, and snow/ice

accumulation. It’s not the most advanced model out there—the GCMs that climate

scientists use (“Global Climate Model” or “General Circulation Model” depending

on who you ask) are pretty inaccessible for anyone not familiar with FORTRAN—so

it can’t predict precipitation and doesn’t do too well with exotic cases, but

it’s a big step up from just guessing temperature ourselves.

Planet Parameters

Once it’s downloaded and started, it’ll need a bit of setup.

We’ll start with the settings menu.

“Settings” -> “Terrestrial” will open up a menu

regarding various greenhouse gasses and similar forcings. The free version

doesn’t let us play around with all these settings too much, but we can choose

from several presets. The default, “1951-1980 AD”, represents Earth’s

climate just before the major rise in CO2 levels and has a global

average temperature of about 15 °C

with Earth’s topography.

The help menus can tell you about the other settings, but

the two most notable are “Cretaceous (90 million yr ago)” which is about

9.5 °C warmer, and “Last

Glacial Max (18000 BC)” which is about 5 °C cooler. These are convenient presets for hothouse and icehouse

glacial climate states.

“Settings” -> “Orbital/Astronomical” allows us to

alter the main forcings determining our seasons—in particular, “Axial tilt

(degrees)”, “Orbital eccentricity”, and “Date of perihelion”.

Clima-Sim uses an idealized 360-day year with 30-day months and the winter

solstice at January 1, so find the mean anomaly of the periapsis from the

winter solstice (it’s 180°

offset from the argument of obliquity, which I use in my spreadsheet), divide

that by 30 to determine the month (1 = January, 2 = February, etc.), and multiply

the remainder by 30 to determine the day. Though we can set these values

however we like, Clima-Sim’s limited circulation model makes it unsuited for

high obliquities or eccentricities.

“Semimajor axis (A.U.)” only affects insolation, not

year length; it can be used to adjust average global temperature, but doesn’t

reflect the stronger seasons of longer years. “Hours in solar day” only

affects the daily range of temperatures, and not atmospheric circulation or year

length.

Terrain

Clima-Sim uses a fairly low-resolution grid of cells (1296

at most) for its simulation, to help limit computation time. Each cell

represents the same area of the surface (hence the “stretching” towards the

poles) and we have to specify a dominant surface type and elevation for each

cell, though there is some interpolation between cells in the simulation.

When you erase the continents, all cells default to water

(which includes ice sheets over water), so we have to draw in land areas in the

4 land surface types that we sketched out in the last section: Permanent Ice,

Dense Forest, Grass, and Desert. Clima-Sim uses these to

determine albedo.

There are 4 levels of elevation, which must be specified after

placing surface types: land areas will start by default as fairly flat

(0-1000 m), and we have to draw in areas of low mountains (1000-2000 m),

medium mountains (2000-4000 m), and high mountains (>4000 m). These

are used to determine air flow and surface temperature.

Conveniently, Clima-Sim allows us to import a map and

display it as a background to the map screen, to help draw new continents. To

do this:

- Open your equirectangular map in your image editor of choice (paint.net is my go-to).

- Resize the map to 720 pixels wide by 420 pixels tall.

- Save this as a .bmp or .jpg file (any name will do) and place it in the “clima-sim” folder.

- Open Clima-Sim

- Select “Erase Continents”

- Select “Display” -> “Use imported background map (toggle, off and back on for new selection”

- Select your map file

You can then use this map to fill in Clima-sim’s grid

However, the free version of Clima-Sim doesn’t allow you to save new

topography, and is also somewhat prone to crashing (in particular, avoid

dragging the cursor from inside to outside the map area with the mouse button

held down while drawing terrain). So to save some frustration and ensure

consistency across sessions, I suggest determining these terrain types outside

Clima-Sim. For your convenience, here’s a rough copy of the grid the program

uses:

Overlay this on your resized map, and fill it in with

high-contrast colors to create 2 maps: One for surface type and one for

elevation. In each case you’re trying to represent the dominant terrain in most

of the cell, though it may be worth exaggerating isolated islands or mountains,

or substantial features that cross multiple cells but don’t occupy the majority

of any one. For reference, you can open up Clima-Sim and select “Display”

-> “Draw world map outline (toggle)” to see how the default terrain grid

compares to Earth’s topography. Note how New Zealand is large enough to merit a

cell of land, but Hawaii is not.

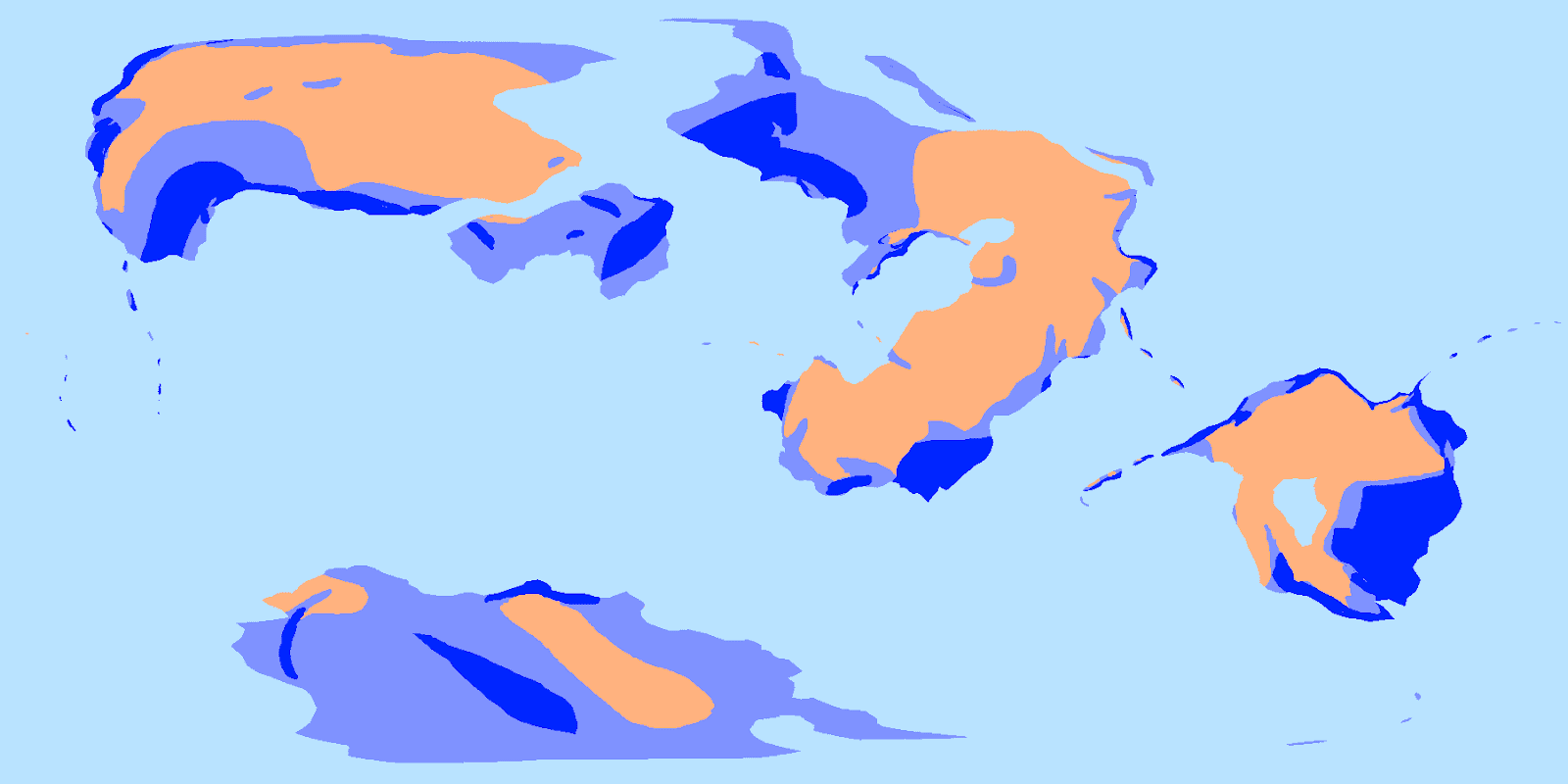

For Ae, here are my grids for surface type (top) and

elevation (bottom) (after adjusting the ice caps to match the simulation, as I'll describe in a moment):

So now the process of drawing terrain is:

- Erase Continents

- Import surface type map

- Draw surface types (water is the default, so we only need to draw land types)

- Import elevation map

- Draw elevation (again, fairly flat is the default, so we only need to draw mountains—if you misclick and place mountain on a cell that should be flat, placing down a surface type again should reset the elevation).

Simulating Climate

Input your terrain, make sure you’ve input the right orbital

parameters and selected the right preset for forcings, toggle off the imported

map so it’s not in the way, and now we are finally ready to begin the climate

simulation. To do so, make sure that “Run mode” is set to “Full run

(does three above in order, initialized with zonal temperatures)” and press

“Start Model Run” in the upper right corner.

Once the run completes, it will display average annual

temperatures at sea level. We should make a couple adjustments first to ensure

accuracy:

- Select “Options” -> “Elevation options” -> “Show actual surface temperatures”. This will display temperatures adjusted for elevation, with temperature dropping by 4.46 °C per kilometer of elevation above sea level.

- Select “Options” -> “Isotherm Quality” -> “High (slow but smooth)”. Fairly self-explanatory.

Near the center of the controls is a dropdown menu for

different months. This may be worth playing around with a little, but the most

important months are July and January (2) (the January at the end

of the simulation, not the start), which have their own shortcuts below this

menu. These should represent the seasonal extremes—summer in the north

and winter in the south for July, and winter in the

north and summer in the south for January (2)

(worlds with high eccentricity and periapsis not aligned with a solstice may

have different seasonal peaks; right-click on the map somewhere in the mid

latitudes to see the local temperature curve across the year, and survey

multiple such locations to get a sense of the seasonal peaks across the

planet).

The first time you run the model, you should check how the

distribution of ice caps compares to the summer temperatures in each

hemisphere. There should be no land cells below 0 °C without permanent ice, and no cells above 0 °C with permanent ice. If

there is a mismatch, alter the initial surface type map and rerun the

simulation (as the initial albedo of ice will affect the final outcome), and

iterate until ice distribution matches modelled surface temperature.

Similarly, there

shouldn’t be any dense forests in cells below 10 °C in summer—though, as we’ll

see, Clima-Sim isn’t totally accurate for some coastal temperatures at high

latitudes, so there’s a bit of leeway here for western coasts.

If you find that

you don’t like the distribution of ice (and you may also want to peak ahead a

couple sections to the climate bands to get a sense of how they’ll turn out)

then you can adjust obliquity and eccentricity to alter the seasonal cycle, or

adjust insolation (by adjusting the model’s semimajor axis) to alter average

temperature for the whole planet.

In the specific

case of Teacup Ae, I found the original parameters resulted in large areas of

Steno and Hutton that remained cold year-round and would have ended up as

tundra, so I’ve decided to increase obliquity to 25°, and move the argument of

obliquity to 120°—expanding the temperate and continental climate bands,

especially in the northern hemisphere (I also increased the semimajor axis to 1.01,

which reduced the average global temperature to about 16 °C).

Exporting Maps

Once we’re happy with the overall global temperature

distribution, we should export the temperature maps for the next steps. Every

time you generate a new map with Clima-Sim (usually by changing the month

displayed) the map displayed is automatically saved as “lastmap.bmp” either in the “clima-sim”

folder or in the same directory as the map overlays you imported. When you’ve generated a temperature map you

want to save, you can rename this file (open it first to confirm it’s the map

you want), and the program will generate a new file for the next map without

altering the renamed file.

The default maps are a bit cluttered, so I like to select “Display”

-> “Isotherms only” and “Options” -> “Isotherm color” ->

“Black”, then import a blank white image as the background. This lets me

display an image of just the isotherms (lines of equal temperature), that I can

then overlay on more accurate maps of the landmasses of Ae:

|

| Note that the program adds an extra line of pixels to the bottom. |

These isotherms don’t extend all the way to the edges of the

map, and will probably have some odd gaps, so keep Clima-Sim open as a

reference for marking out temperature zones.

You can also use “Options” -> “Isotherm spacing”

to alter the temperature step and numbers of isotherms.

We’ll need at least 4 maps for the process of marking out

climate zones:

- 2 maps with medium isotherm spacing for both of the seasonal peaks (typically July and January (2)).

- Having maps with wide isotherm spacing for the seasonal peaks is convenient as well.

- For each hemisphere we’ll also need a map with wide spacing either 2 months before or after peak summer (whichever is warmest at high latitudes where the mean annual temperature is around 10 °C).

- Having a mean annual temperature map may be cool as well, though not necessary for this tutorial.

I’ll trust that you can figure out the process of resizing

these maps back to equirectangular (2:1 width/height ratio), smoothing out the

isotherms, converting them to temperature zones, and filling in the edges of the

map—it’s mostly just an elaborate process of filling in the lines or

interpolating between lines. If you want to stay fully realistic, there should

be only one temperature zone across the entire top and bottom boundaries, as

these represent points, and temperature zones should wrap around the left and

right edges.

Step 3: Ocean Currents and Mountains

A special note: I’m doing this step before marking climate bands because I want to have consistent temperature maps, but if you don’t care about that then it may be easier to do this after Step 4, because there are less boundaries to worry about.

Clima-Sim does a pretty good job of simulating global

climate, and it does try to account for ocean currents, but ultimately it comes

up a bit short. Below is a comparison between the average temperatures modeled

by Clima-Sim for Earth’s topography, and the actual recorded temperatures for

1951-1980 (the period used to calibrate Clima-Sim), showing discrepancies at

high-latitude coastal areas of 10 °C

or more (in the northern hemisphere, at least; the south has little land area

at the relevant latitudes):

|

| Blue areas are warmer in reality than simulated, red areas are cooler. |

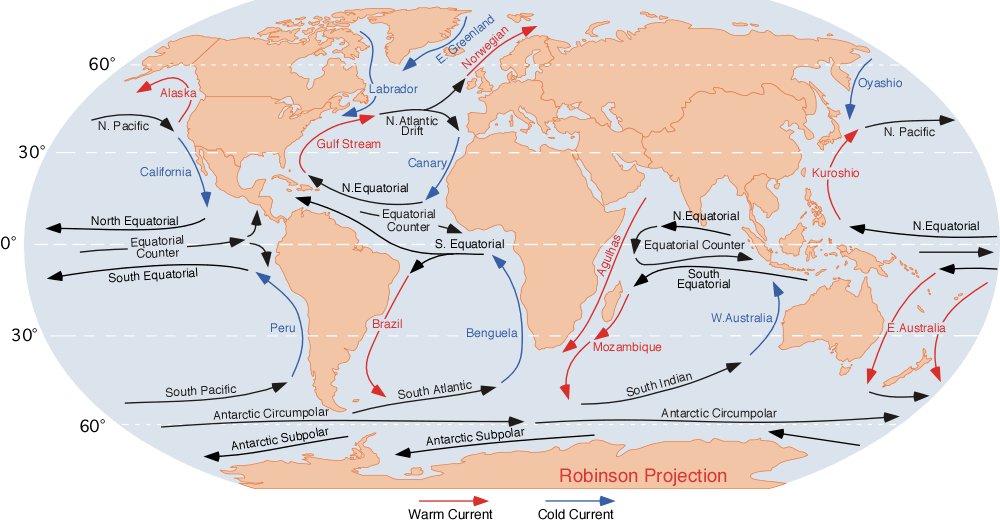

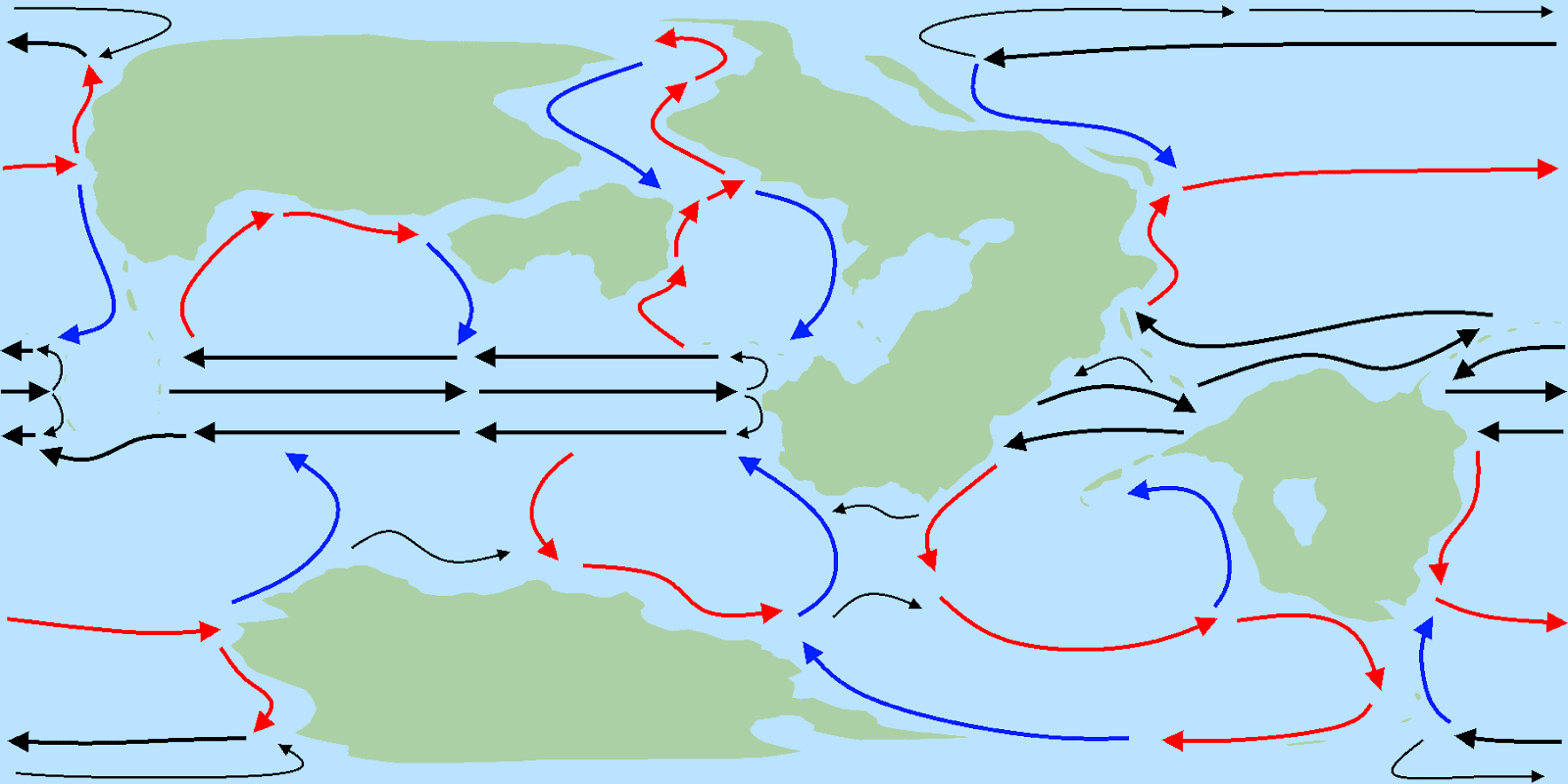

Compare that with

Earth’s dominant ocean currents, which carry warm waters poleward in some areas

and cool waters equatorward in others:

|

| Dr. Michael Pidwirny |

Drawing Currents

Now, just to

prevent some confusion: if you’ve spent some time on worldbuilding forums or

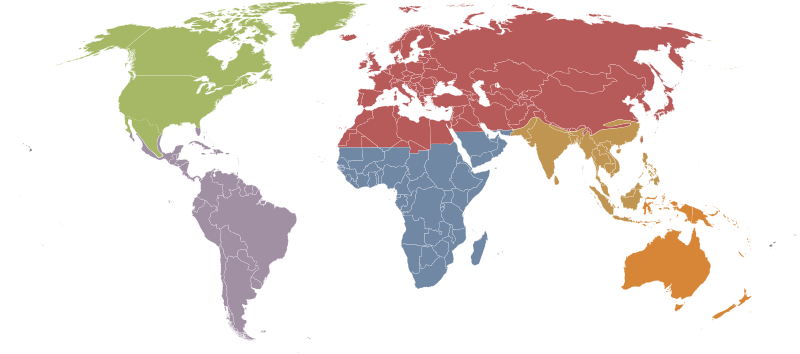

watched this video, you’ve probably seen current maps that

look something like this:

Simply put, this map isn’t actually depicting currents. They

don’t stick quite that close to the coasts, and they don’t take hard turns to

shoot straight across the oceans. This is more of a depiction of the effects

that currents have on land. It’s typically used as a heuristic for determining

climate zones without the need for temperature or precipitation data, and in

that sense it works well enough, but many people—unaware of the abstracted

nature of these maps—often get caught up trying to work out the mechanics of

minor coastal features, when in reality they’re not that important to global

climate. As I’m using ocean currents more narrowly to adjust temperatures in

certain regions, I can stick with a more direct depiction of their actual

paths.

In every ocean a single current, the equatorial

countercurrent, flows east, generally sticking close to the equator but

deflected somewhat by coastlines at a low angle to the current’s direction of

flow.

Once this current hits a coastline (or a large archipelago)

that’s more perpendicular, it splits and curves around to two currents, the equatorial

currents, flowing west, around 5-10°

latitude north and south of the countercurrent.

These flow back across the ocean. Some water begins curving poleward

within a couple thousand kilometers of leaving the coast, but the main currents

will be where the countercurrents encounter the eastern coasts of a landmass

along the equator, or where a landmass lies directly to the north or south

within about 50° latitude.

|

| Typical current patterns. |

These currents then flow poleward along the coasts. They

don’t flow too close to the coasts, mind; the main flow is often several

hundred kilometers offshore, and the currents won’t sweep into bays and coastal

seas. There are currents circulating in these areas, but over such short

distances they perform too little heat transport to be relevant to climate. We

can think of these bodies of water as “inheriting” the heating or cooling

effect of whatever current flows past any seaways connecting it them to the

oceans. This is true even where there is an open east-west seaway between continents;

some water will flow through, but the main poleward current will continue.

Similarly, a parallel north-south seaway between a large landmass and an

offshore island can have a side current flowing through it and rejoining the

main current.

This is not to imply that straits have no impact at all; in some cases they can provide a passage for warm currents into areas that would otherwise be affected only by cold equatorward currents.

These currents bring warm equatorial waters poleward, so we’ll mark them as warm currents.

These currents bring warm equatorial waters poleward, so we’ll mark them as warm currents.

The poleward currents continue along the coasts through the

Hadley cells, but on entering the Ferrel cells the combination of the Coriolis

effect and westerly winds start pushing them east. They separate from the

coasts at around 40-50° latitude,

depending on the angle of the coastlines (more straight north-south oriented

coastlines will cause more poleward separation) and then turn east across the

ocean. They’ll generally keep a slight tilt poleward, though they can curve

equatorward to meet the poleward tip of a continent that extends partially into

the Ferrel cell from the Hadley cell. These currents still carry water warmer

than surrounding waters, so we’ll keep them marked as warm currents.

Once this current encounters

a coast, it will split again: one branch will flow along the coasts equatorward

and merge back with the equatorial current. The other flows poleward along the

coast. Similarly to before, we can also expect an equatorward current wherever

the eastward current passes poleward of an equatorial landmass.

The poleward

current is still warm relative to surrounding waters, but the equatorward

current is now carrying relatively cool water towards the equator, so we’ll

mark them as cold.

If no landmasses

block the poleward current (or sea ice, which forms where the sea remains below

-2 °C in summer and does just about as good a job blocking surface currents),

it will continue to around 80° latitude, where the polar easterlies will cause

it to curve back west until hitting a coast (again, possibly curving slightly

equatorward to meet one if necessary), and then flow equatorward to merge with

the mid-latitude currents. If the pole is open water, you can expect a small

circumpolar current flowing west around the pole, though this has little impact

on temperature.

There are a few key

patterns that emerge here. For one, there is circulation throughout the ocean;

nowhere does a current flow into a body of water without there being

another current flowing out.

Another is the

formation of large circulation cells, like in the atmosphere—but in the oceans

they’re known as gyres. Gyres should form off the west coasts of all

large landmasses at low latitudes, turning clockwise in the northern

hemisphere and counterclockwise in the south.

Of course, even this is an abstraction of currents to some extent. Water is in motion all across the ocean, and a complete map of surface currents would look something more like this:

But this method does represent the main flow of currents, while hopefully being intuitive enough to chart out for your own worlds.

Of course, even this is an abstraction of currents to some extent. Water is in motion all across the ocean, and a complete map of surface currents would look something more like this:

|

| NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center Scientific Visualization Studio |

But this method does represent the main flow of currents, while hopefully being intuitive enough to chart out for your own worlds.

Currents and Temperature

To have an impact on climate, currents need to move pretty

far poleward or equatorward, something like 30° latitude or more—but they’ll retain their heating or cooling effect

when crossing the ocean. This means the temperature effects should only be

significant where there are large, uninterrupted oceans or major channels extending

far across latitudes. This also means that the warming or cooling effect of a

current is not lost the moment it changes directions; a poleward current that

turns equatorward will still warm the nearby coasts, until it moves more than

around 10° latitude and the water temperature begins to approach the

surrounding land temperature.

Starting with

Clima-Sim’s output, the biggest impacts will be at around 50-70° latitude:

western coasts here will be warmer thanks to poleward currents, and eastern

coasts cooler due to equatorward currents. Per Earth’s example, the former

effect seems to be slightly stronger; the difference between Clima-Sim’s output

and the adjusted temperature should peak at around 15 °C warmer on west coasts

and 10 °C cooler on east coasts at close to 60° latitude for both. Closer to

the equator, some minor heating of eastern coasts and cooling of western coasts

at 20° latitude is reasonable, but it shouldn’t be a huge change from

Clima-Sim’s output.

|

| Areas of temperature adjustments for currents: red areas will be made warmer and blue areas made cooler. |

At the equator

there will also be heating of eastern coasts by the equatorial currents, moreso

the farther these currents have traveled. These currents pick up heat as they

travel west, and it can build up on the western side of the ocean over several

years until it causes a temporary reversal of prevailing winds to carry heat

back east. In the Pacific these are called “El Niño” events and occur

about every 5 years, warming South America and cooling Australia. These events

are too subtle and infrequent to be worth accounting for in this tutorial

(except perhaps to inform distribution of coral reefs), but may be worth

keeping in mind as a likely feature of any broad equatorial oceans.

All that in mind,

here are the adjusted temperature maps for Ae:

Mountains

One last adjustment we can make is to mountain temperatures.

The low resolution of Clima-Sim’s simulation grid means that it may not quite

reflect the shape of high-elevation cold zones accurately, so you’ll have to

make some adjustments for that.

|

| Typical Clima-sim output for a mountain range (left) and more realistic adjustment (right) |

It also seems to slightly overestimate temperatures on high

mountains: If you have any large plateaus above 4 km elevation, their interiors

should have average temperatures below 10 °C.

And so, at long last, here are the final temperature maps

for Ae (with contour lines at 1 km increments):

Step 4: Climate Bands

The temperature data we’ve gathered is enough to mark off some

of the groups in the Köppen scheme—what I’ll refer to as the planet’s climate

bands. The procedure is fairly straightforward: Take the temperature maps

from clima-sim (with adjustments for ocean currents and mountains, if you’re

doing that before this step), overlay them on a map of your world, and starting

from the equator mark out all land areas above the given temperatures for each

band in summer or winter, as specified.

Actually, rather than starting with the geographical equator,

let’s mark the thermal equator for each season: This is the line near

the equator with the highest temperature in each line of longitude. If you’ve

got a lot of high terrain near the equator it might get a pretty jagged, but

that’s alright for now.

Next, mark off the regions in each hemisphere which are at

least 18 °C in winter.

This is the tropical band, with

Group A climate zones.

Next, in the remaining area mark off the regions which are

at least 0 °C in winter.

This is the temperate band, with

Group C climate zones.

(On further review of Koppen climate zones, it appears that you should then remove any areas within this band that are less than 10 °C in summer, as these areas will be tundra. In most cases this should only appear in some equatorial mountain ranges).

Within the temperate band, mark off the regions which are at

least 22 °C in summer. These are the hot-summer zones of the temperate band;

remaining temperate regions are cool-summer

zones.

Next, in the remaining area mark off the regions which are

at least 10 °C in summer.

This is the continental band, with

Group D climate zones.

Within the continental band, take a time 2 months before or after peak summer

(whichever is hottest) and mark off regions which are at least 10 °C. This is the humid continental zone; remaining continental regions are the subarctic zone.

Next, in the remaining area mark off the regions which are

at least 0 °C in summer.

This is tundra, the ET

climate zone.

The remaining area, which is below 0 °C even in summer, is ice cap, the EF climate zone.

That settles the land climate bands, but while we’re here we

can also mark off a couple of informal climate areas at sea:

Areas above 18 °C

in winter can support coral

reefs in shallow waters (presuming the temperature limits are the same as

for reefs on Earth).

Areas below -2 °C

in summer will have permanent

ice sheets.

Remaining areas below -2 °C in winter will have seasonal ice sheets.

All this is enough to give us a general idea of the planet’s

climate, and it’s at this point that we should decide whether to commit to this

climate or restart with altered orbital characteristics or topography. If

you’re in a hurry, you could stop here and try to determine climate zones by

general location rather than simulating winds and precipitation; but for this

tutorial, we’ll carry on to the end.

Step 5: Winds

|

| Typical seasonal temperature (top), air pressure and winds (middle), and precipitation (bottom). (the original page where I got these animations has disappeared but is archived here and versions interpolated to higher resolution are also available here) |

Further subdivision of Koppen climate zones requires

precipitation data, which Clima-Sim doesn’t provide. Precipitation on Earth mainly

originates in the oceans: water evaporates in warm seas, is carried inland, and

then—if conditions are right—condenses and falls onto land. Sussing out the

connections between temperature, pressure, wind, and precipitation can be

tricky, and—as I’ve learned my self—trying to find simpler shortcuts can often

have very misleading outcomes. But we’ll take it all step-by-step.

(When first published this tutorial contained a much

different version of the next few sections. In retrospect, the methodology

employed there was both too simple in concept and too complex in execution.

This new approach sacrifices some precision—I’m leaning much more heavily on

your personal intuition and artistry to divide up certain zones—but hopefully

makes up for it in accuracy in more closely modelling the actual mechanisms of

global climate).

Global Circulation

To start, we’ll mark out the likely location of the ITCZ

in summer and winter. It should roughly follow the thermal equator, but a

little more smoothed out so it’s not zigzagging through mountain ranges.

Compare Earth’s seasonal thermal equators and ITCZs for reference:

|

| Top: Seasonal temperature and thermal equator. Richter 2014. Bottom: Seasonal ITCZ. Mats Halldin, Wikimedia. |

Here’s how I’ve marked them out for Teacup Ae (blue is the ITCZ, red is the thermal equator):

The tropical easterlies flow towards the ITCZ, not the equator, so as the ITCZ moves with the seasons the prevailing winds in the regions it passes over will switch direction. This is the primary cause of monsoon winds: onshore winds in summer bring rains, and offshore winds in winter cause dry conditions.

The further we get from the equator and towards the poles,

the more our neat model of convection cell boundaries and prevailing winds

becomes a suggestion rather than a law. Rather than a single high-pressure belt

at the horse latitudes, we instead find a number of distinct subtropical

highs.

These tend to be strongest over cold areas, so they’re best

identified by patterns of ocean currents. In the current map you made back in

Step 3, you should find a number of large ocean gyres between around 10° and 50° latitude, turning clockwise in the northern hemisphere and

anticlockwise in the south. The cold, equatorward legs of these currents—which

should lie along the western coasts of major landmasses—will create our

subtropical highs, just offshore to the west. Like the ITCZ they’ll shift with

the seasons, but more subtly; place them a bit further towards the equatorward

side of the gyre in winter (centered around 25° latitude, depending on the

overall extent of the gyre) and a bit towards the poleward side in summer

(centered around 35° latitude).

Here they are for teacup, marked in red (with currents shown as well).

- A landmass is large enough to support such a high-pressure zone if it’s significantly cooler (~5-10°) than oceans at the same latitude.

- Multiple nearby landmasses without warm oceans separating them can be counted as one landmass

- The high-pressure zone will appear roughly in the center, but shifted towards any particularly cold regions (relative to latitude) such as large mountain plateaus.

- They’ll generally be a bit further poleward than the ocean subtropical highs, and can even appear on landmasses near the poles.

If we wanted to, we

could dig further into patterns of pressure and add low-pressure zones (which

seem to form over continents in summer and high-latitude oceans in winter) but

the rules there are even more vague and these high zones are sufficient to get

a pretty good sense of prevailing winds.

Prevailing Winds

Prevailing winds are, as in the idealized models we’ve

looked at before, a product of pressure and the Coriolis effect. Winds tend to

blow from high to low pressure zones, but the Coriolis effect causes winds

blowing north or south to deflect from a straight path; to the right in

the northern hemisphere, and to the left in the southern

hemisphere. On a world covered in homogenous ocean, this would create the

neat convection cells of those models, but on a world of mixed continents and

oceans we get a more complicated jumble of winds that bears some overall

resemblance to the idealized case but deviates from it in many places.

To start off, we can mark the anticyclones. These

appear over high-pressure zones as air moving down its pressure gradient is

curved by the Coriolis effect. Though the path of a lone object in a vacuum

might only be gradually altered by this effect, the interaction of many air

masses on Earth accentuates the effect until air no longer moves directly out

of highs but instead spirals tightly around them; turning clockwise in

the northern hemisphere and counterclockwise in the south

(same as the underlying ocean gyres). We’ll just mark winds in the cores of

these anticyclones for now, and build them out from there:

Next, we’ll mark out the trade winds, or tropical

easterlies, which dominate in the tropics. For the most part, they do

actually behave as in the idealized models; blowing equatorward and curving

towards the west until they meet at the ITCZ blowing nearly directly west. But

there are a few wrinkles.

The trade winds mostly originate from the subtropical highs,

so the position of these highs influences how steeply the winds approach the

ITCZ, and where it passes before then. On the eastern sides of the highs, it’s

typical for a wind to begin moving east and then curve around to the west.

You should have some winds crossing the equator from the

winter hemisphere to the summer hemisphere. When this happens, the influence of

the Coriolis effect switches direction, so rather than curving to the west,

winds will curve to the east—and they can do so quite quickly.

Tall mountain ranges have a subtle effect on winds,

corralling but not blocking them. Think of it like placing a block of wood in a

small stream: if you place the block across the whole stream, the water will

just build up and flow right over it; but if you place the block at a shallow

angle across part of the stream, it will push the flow of water around it.

All that in mind, here’s how I’ve drawn with the trade winds

for Teacup Ae (with the ITCZ shown in blue and the equator shown in red):

Moving out of the tropics, winds become altogether less

regular and ordered. The general process here is to expand out the anticyclones,

though with a generally stronger tendency for winds to move east or west rather

than north or south.

However, neighboring anticyclones will of course produce

winds at odds with each other, so somewhere between them (generally a bit

closer to the anticyclone on the western side, especially over oceans) the

opposing winds will meet in a front, separating the winds originating

from either anticyclone. Because of the way winds spiral out of anticyclones,

these fronts will usually appear in a slant, more equatorward in the west and

more poleward in the east—though this is most true for neighboring highs at the

same latitude.

I already had this in mind when drawing the winds, but here are the fronts shown explicitly, in purple.

Near the poles these wind patterns aren’t terribly

consistent, but you might have easterly winds emerging from the pole in winter.

Upwelling

Before we move on to precipitation, there’s one subtle

effect of prevailing wind worth noting here: Where the winds blow parallel to a

coastline, they drag the underlying waters with them. When this happens over

great distances, the Coriolis effect causes the path of the water to curve. If

it curves offshore—which should happen where the coast is to the left

relative to the wind direction in the northern hemisphere and to the right

in the south—then this creates a suction effect which pulls water up

from the deep ocean to the surface.

|

| Wind/land orientations that result in upwelling in the north (top) and south (bottom) hemispheres. |

This upwelling brings up a good deal of nutrients

from the ocean floor, which is beneficial to plankton growth in coastal waters.

This in turn provides more food for fish (or other aquatic life) and so increases

catches for fishermen.

On the other hand, upwelling also brings up cold water,

which inhibits coral reef formation save for in the warmest areas of the world

close to the equator. Less importantly, it also causes fog on the nearby shore.

Winds shift with the seasons, of course, so upwelling may be

seasonal; broadly speaking, the benefit to plankton and fish should be greatest

in summer, when plankton is most productive, and the detriment to coral

should be greatest in winter, when sea temperatures are closest to the

minimum comfortable for coral (though close to the equator the seasonal

temperature difference is minor save for in cases of high eccentricity or

obliquity, but this is also where the warmest seas are so upwelling is less of a problem anyway).

In case you’re wondering, where winds blow in the opposite direction relative to the coast and the Coriolis effect pushes water into the shore, this causes downwelling; warm and nutrient-poor but oxygen-rich surface water is forced down into the deep ocean. This is important for global ocean circulation and deep sea life, but has no local effects on the surface worth concerning ourselves with here.

In case you’re wondering, where winds blow in the opposite direction relative to the coast and the Coriolis effect pushes water into the shore, this causes downwelling; warm and nutrient-poor but oxygen-rich surface water is forced down into the deep ocean. This is important for global ocean circulation and deep sea life, but has no local effects on the surface worth concerning ourselves with here.

Step 6: Precipitation

|

| Global average precipitation on Earth in each month. PZmaps, Wikimedia. |

Precipitation requires both horizontal and vertical movement

of air. First, horizontal motion in the form of winds is necessary to carry

moisture from the oceans over the land. Then, upward motion of air is necessary

to cause air to expand and cool, such that the moisture condenses as falls down

as rain or snow.

We’ve already identified the winds, but the upward motion

can be trickier to work out. All sorts of subtle effects and resonances can

play into them, and lacking a complete simulation of global air flow we can

only guess at how it all shakes out. But there are some common patterns we can

follow. We’ll add rain in steps, each trying to account for one major influence

on global rainfall, marking land regions as “very wet”, “wet”, or “dry”.

Warm Currents

First off, we’ll add rains extending downwind from all

coasts affected by warm ocean currents. These currents don’t necessarily induce

rain on their own, but they do induce high rates of evaporations and so create

large masses of warm, humid air, that will produce rain at the slightest

agitation—something we can assume will happen sooner or later in the chaotic

atmosphere.

First off, compare your maps of currents and seasonal

prevailing winds, and mark off all the ocean coastlines with onshore winds

(even at a very shallow angle to the shoreline) on coasts that are influenced

by warm currents (for this purpose, this includes the equatorial currents and

countercurrents but not any other “neutral” currents outside the tropics). Don’t

worry about coastlines on small seas totally or nearly isolated from the ocean

(like the Caspian or Black seas); these don’t contribute much to the rainfall

of the surrounding areas.

Then, in each season mark off the land regions by these

coasts as “wet”, and carry the wet zone downwind until hitting a barrier to

airflow:

- A front or the ITCZ, where the air meets opposing winds blowing in a different direction.

- High topographic relief. The air can follow a gradual slope up to around 4,000 m elevation, but if you encounter a steep mountain range then carry the rain up to the ridge and stop it there, leaving downwind regions as a dry rainshadow. For now, we’ll say this applies to any relief of ~1,000 m or more. But if there’s a small range, then winds may converge again downwind, such that the rainshadow is a small pocket rather than a strip across the whole continent.

- If nothing else stops it, the rain will peter out about 2,000 km downwind from the coast it originated at. It’s pretty difficult to measure distance on a flat map like this, so it’s probably best to load up the map in GPlates and use the measuring tool there to judge this.

|

| ITCZ, fronts, winds, and elevation at 1,000 meter intervals all shown for reference. |

ITCZ

Strong upward motion of air occurs all along the ITCZ, and

this combined with converging winds will tend to make it the rainiest area of

the planet—though far inland there can still be rainshadow effects.

To simulate this, we’ll mark out a “zone of influence” (shown here in light blue) centered on the ITCZ extending north and south by about 15° latitude—but perhaps a bit wider on

the western shores of large oceans, and a bit thinner near the subtropical

highs (basically, make sure it doesn’t overlap the highs you’ve marked out, and

where they’re nearby take a chunk out of the zone of influence).

First off, any pre-existing wet areas within this zone can

be upgraded to very wet.

Next, add wet areas on coasts with onshore winds in this

zone that don’t have them already (i.e., coasts with cold currents) and carry

them downwind, following the same rules as before: don’t cross fronts of the

ITCZ, don’t cross mountains, and don’t go more than 2,000 km downwind from the

ocean.

You can also add a bit of extra wet area around the edges of

the very wet areas; don’t feel compelled to add it around all the edges, but

maybe carry the wet areas a little further inland and curving in a little

tighter around the edges of mountains, and generally just smooth things out.

Fronts

Fronts occur when two mass of air of different temperatures come

into contact; the hot air will rise over the cold air, and the upward motion

encourages rain. Some fronts are stable, semipermanent features like the ITCZ,

but many are unstable features that won’t last long but will form repeatedly in

the same area and move through them. We won’t distinguish these here; we’ll

just say that we expect some kind of front to appear in areas where equatorward

and poleward winds are converging.

The process here is broadly similar as that with the ITCZ:

Mark out zones of influence (shown here in purple) for each front where heavier rains will occur.

These will generally be wider the further apart the centers of the anticyclones

creating them are (representing more leeway for the fronts to move back and

forth). They shouldn’t overlap the subtropical highs, and they shouldn’t extend

too far into the zone of influence of the ITCZ, as the trade winds dominate

there.

Again, any preexisting wet areas in these zones will be

upgraded to very wet.

|

| For visual clarity, preexisting very wet zones aren't shown. |

And also again, add wet areas where there are onshore winds

from coasts with cold current regions (even if that coast isn’t within the zone

of influence, the winds will carry moisture into the zone so long as it isn’t

more than 2,000 km downwind).

But remember that these fronts aren’t as stable or

stationary as the ITCZ; imagine how the winds would change if the fronts moved

to either side of the zone of influence, and where those winds could carry

moisture to, then add wet areas there as well.

Orographic Rains

I’ve already explained these a little: when winds encounter

high relief, the air is pushed upwards and water vapor rains out. Find areas of

the world where winds encounter sharp relief of 1,000 meters or more, and mark

out zones of influence (shown here in orange) within a couple hundred km of the upwind side—save only

for regions close to the subtropical highs.

Once more, preexisting wet areas become very wet.

And new wet areas can be added anywhere where the oncoming

winds haven’t travelled more than about 3,000 km from the sea (a bit more than

usual, because this is a pretty strong effect) or already crossed a major

mountain range.

Lee Cyclogenesis

Usually the downwind (“lee”) side of mountains have dry rain

shadows, but occasionally the opposite can happen. When prevailing winds pass

directly over a high mountain range, a low-pressure zone can form on the lee

side. This draws in the surrounding air, creating a local cyclone (hence the

name; formation of cyclones on the lee side of mountains). If there happens to

be a large body of water nearby, this can draw moist air up onto the mountains,

creating rain.

So look for areas of world that satisfy these conditions:

winds passing nearly directly over high mountains (say, over 2,000 meters

relief), and oceans within a couple hundred kilometers of the downwind side

(the moisture still can cross over the mountains). There probably won’t be more

than a couple cases across the planet (shown here in magenta).

Again, existing wet areas are upgraded to very wet…

…and new wet areas can be added extending from the coast to

the mountains.

Polar Front

I mentioned before that you might expect to get some

easterly winds near the poles, and a more complete model of winds might have

added an extra high-pressure zone near the coldest area of the planet in

winter, creating an extra set of fronts circling the world at high latitude.

But this polar front is highly variable and mobile, more so than the local

fronts at mid-latitude. Rather than a static feature it forms a wavy pattern of

lobes that circle the world travelling east, bringing at least some rain to

most areas at high latitudes.

To model this, we’ll mark a zone of influence (shown here in green) for the polar

fronts extending from the poles. They’ll reach to about the poleward edge of

the subtropical highs, around 40°

latitude in summer and 30° latitude in winter, and we’ll take

chunks out around the subtropical highs and the influence of the ITCZ; try to

draw the resulting boundaries such that they roughly follow along the lines of

prevailing winds.

The polar front is a weak and transient feature, so we won’t

add any very wet areas. But we will add wet areas extending inland from all

coasts, even with offshore winds; carry these wet areas about 2,000 km

downwind, 1,000 km upwind, and 1,500 km across winds.

That about wraps up our mapping of precipitation; any

remaining areas can be marked as “dry”.

This whole methodology is, of course, not terribly precise,

but it is about as accurate as we can reasonably get without access to better

software and the computing power to run it. It is, at any rate, good enough to

get something approaching the overall patterns and diversity of climate we see

on Earth If you’ve done everything right, you should end up with large zones of

high precipitation along the ITCZ well into the interiors of continents, on

mid-latitude east coasts and high-latitude interiors in summer, and on

high-latitude west coasts in winter.

This last step gives us the final bit of information we need

to finish up the climate mapping. But don’t throw out the other maps you’ve

made along the way; in particular, ocean currents and prevailing winds will

direct ocean trade by sailing ships later on.

Step 7: Climate Zones

The precipitation data in the last step isn’t precise enough

to map out all out climate zones, but it can gives us some good guidelines to

work some.

First off, our tundra

(ET)

and ice cap (EF) zones can be left

untouched; precipitation matters little in these cold climates, though we can

generally expect them to be fairly dry.

Next, we’ll deal with the arid regions in the remaining land;

those that are dry in both summer and winter. These will be Group B climates: desert (Bw) or steppe (Bs).

We can mark them as desert by default, and then fill in the

edges with steppe; there should always be some steppe between deserts and other

climate zones (but there need not be steppe between deserts and the sea). On

flat ground, the steppe will appear in boundary strips about 100-300 km wide in

the tropics and twice as wide at higher latitudes, and small patches of arid

land can be completely filled in with steppe.

In mountains the boundary thins, and on steep mountain

slopes it can thin down to just a few kilometers. Low highlands with shallow

slopes will tend to have the opposite effect, though, creating broader regions

of steppe and patches of desert.

Once that’s done, we can divide them up by temperature:

Deserts and steppes in the tropical and temperate climate bands will be hot desert (Bwh) and hot steppe (Bsh); those in the continental band

will be cold desert (Bwk) and cold steppe (Bsk).

Remaining areas in the continental band can be left as-is,

as humid continental (Dsa/Dsb/Dwa/Dwb/Dfa/Dfb) and subarctic (Dsc/Dsd/Dwc/Dwd/Dfc/Dfd) zones.

Next, remaining areas in the temperate band will contain Group C

climates. Mark areas that are dry in

summer (but still wet or very wet in winter) as mediterranean (Csa/Csb/Csc). Remaining areas (that are wet or very wet in summer, regardless of their condition in

winter) will be humid subtropical (Cfa/Cwa)

in the hot-summer regions and oceanic (Cfb/Cfc/Cwb/Cwc) in the cool-summer

regions.

Finally, the tropical band, which is a bit trickier. These

will be Group A climates: tropical

rainforest (Af), tropical monsoon (Am), and tropical

savanna (Aw/As).

We’ll start out by marking out areas that are very wet in both seasons as tropical rainforest (Af),

areas that are wet in both seasons as

tropical monsoon (Am), and areas that are wet

in one season and dry in the other as

tropical savanna (Aw/As).

The remaining areas will be split between zones: Areas that

are very wet in one season and wet in the other will be tropical rainforest (Af)

near the equator and transition to as tropical

monsoon (Am) near the edges of

the tropical band and arid zones. Areas that are very wet in one season

and dry in the other will be tropical

monsoon (Am) near coasts,

mountains, and rainforests and tropical

savanna (Aw/As) inland and near

arid zones.

You should try to make sure that there is a continuous

sequence of rainforest-monsoon-savanna-arid zones (though the transition can be

pretty sharp in mountains), and you can touch it up at the end to ensure this.

A couple final adjustments we can make:

- The ITCZ will pass through the areas between it’s seasonal extremes, bringing rain to areas near the equator currently marked as dry. This should shrink the arid zones near the equator and expand the tropical savanna and to some extent the tropical monsoon zones, but not the rainforest, which requires high year-round rain (and also other wet zones in areas near the equator outside the tropical band). This should create a more-or-less continuous wet band across the equator, except for where there are strong rainshadows.

- Conversely, the way I’ve handled rains near the ITCZ can cut into deserts a bit too much near the coasts. Where there are large deserts at mid-latitude (around 20°) make sure they extend all the way to the west coast.

- Some of the high-latitude deserts here have also come out looking a bit odd—largely because it’s hard to judge distance at high latitude in this projection—so I’ll go ahead and adjust those a bit as well.

And that about wraps it up. Of course, this whole process

isn’t perfect, so if you end up with something that doesn’t seem quite right

(odd patches of desert or steppe, a dearth of Mediterranean zones, etc.) or you

just want something slightly different, then by all means you can adjust the

boundaries between climate zones without sacrificing much in terms of realism.

Winds in the Ferrel cells in particular are pretty irregular, so this method may

be a little over-deterministic regarding precipitation at mid-latitudes. But

for my part, I think this map of Teacup Ae works just fine (though I may adjust

it somewhat when I add more detailed topography).

Optional Extensions

These 14 zones include all the most important variations in

climate, and the accuracy of hand-drawn precipitation zones is probably too low

to make more granular climate zone distinctions with any confidence. But if you

really want to have the full set of 31 Köppen climate zones, here’s a

procedure that should more-or-less work:

Tropical Savanna

(Aw/As): Even

formal sources mapping Earth rarely make this distinction, but you can mark

areas that are dry in summer as As, and leave the rest as

Aw

(though also bear in mind the extra savanna you added near the equator for

where the ITCZ passes over, which should remain Aw).

Mediterranean (Csa/Csb/Csc): Regions in the hot-summer areas of the

temperate band are Csa; regions in the cool-summer areas are Csb

if they are above 10 °C at 2 months before or after peak summer, and

Csc if they are not.

Humid Subtropical (Cfa/Cwa): Regions

that are dry in winter are Cwa, remaining regions

are Cfa.

Oceanic (Cfb/Cfc/Cwb/Cwc): Regions that are above 10 °C at 2

months before or after peak summer are Cfb or Cwb,

those not are Cfc or Cwc; Regions that are dry

in winter are Cwb or Cwc, those not are Cfb

or Cfc. Determine zones by overlap of these temperature and

precipitation boundaries.

Humid

Continental (Dsa/Dsb/Dwa/Dwb/Dfa/Dfb): Regions that are dry in summer are Dsa or Dsb,

those that are dry in winter

are Dwa or Dwb, remaining areas are Dfa

or Dfb; Regions that are above 22 °C in summer are Dsa,

Dwa, or Dfa, those that are not are Dsb,

Dwb, or Dfb.

Subarctic (Dsc/Dsd/Dwc/Dwd/Dfc/Dfd): Regions that are dry in summer

are Dsc or Dsd, those dry in winter

are Dwc or Dwd, remaining areas are Dfc

or Dfd; Regions that are above -38 °C in winter are Dsc,

Dwc, or Dfc, those that are not are Dsd,

Dwd, or Dfd.

Note the pattern in the letter designations here: For the

second letter, s zones have dry summers, w zones

have dry winters, and f zones have no dry season; For the third

letter, a zones have summers above 22 °C, b zones have summers above 10 °C extending to 2 months

before or after peak summer, c zones have winters above -38 °C,

and d zones have colder winters.

Generally speaking, you should expect to see Ds

zones mostly near Mediterranean zones, and Dw zones mostly near regions with a

strong monsoon effect (where the ITCZ has moved far from the equator) so you

may need to make some adjustments if you see large regions of them in odd

places.

Here’s the complete map of all Köppen climate zones for Ae

(29 zones, as there are apparently no Dsc or Dsd zones

on Teacup Ae), plus the 4 ocean zones I’ve added.

Impacts of Climate

Now that we’ve done all that, let’s take a tour of these

climate zones to get a feel for what kind of life we might see in them and what

impact they’ll have on the development of civilization (in broad strokes; I’ll

dig deeper into the distribution of natural resources, terrain types, and the

cultural impact of climate in later posts). I’ll also include the formal

definitions for these zones, which I had to simplify for this tutorial, and

some examples from Earth.

A: Tropical Climates

Monthly average temperatures at least 18 °C year-round.

Tropical Rainforest (Af)

At least 2 mm/day of

average rainfall every month of the year.

Examples: Central Amazon; Central Congo; Borneo;

Singapore.

Conditions: These are hot, wet regions with no dry

season. Average temperatures above 25 °C

and rains above 10 mm/day are common. Near the equator, average temperatures

are near-constant but there are often still wet and dry seasons as the ITCZ

moves. Regions nearest the center of the tropical band will have low winds and

wet equinoxes with dry solstices, while further poleward regions are more

influenced by strong trade winds and have a more pronounced cycle of wet summer

solstice and dry winter solstice.

|

| Guadeloupe. Mart.wain, Wikimedia |

Ecology: These are the most diverse regions of the

planets; a single square kilometer can include trees from over 1,000 species.

Consistent rain and sunlight support dense forests, but the rain also leaches

nutrients from the soil; competition for light and nutrients amongst plant life

is fierce. So little light penetrates to ground level that, aside from tree

trunks, it’s fairly clear of vegetation. A single area of rainforest can often

be divided vertically into distinct microbiomes dominated by different species.

Climbing, jumping, gliding, and flight are common adaptations to allow travel

between trees without descending to the ground.

At higher elevations—above 500 m or so—rainforests tend to

have shorter trees and thicker undergrowth. Where the elevation is high enough

for clouds to be below canopy height, cloud forests form, with frequent

fog and extremely moist conditions that support mosses and ferns.

Conversely, at low elevation broad swamps can form along

riverbanks, with permanent or seasonal shallow water over the forest floor.

Society: Beneficial though rainforests are to

wildlife, from a human perspective they’re more hostile. Hunter-gatherer tribes

can thrive on the high productivity and moderate seasons, but to technological

societies these are barriers. Thick plant growth and extremely wet conditions

make travel difficult except by foot, and these regions still include some of

the least accessible areas on Earth. There will typically be large rivers that

make convenient avenues for travel, but these are often bordered by broad

swamps and thick vegetation that make landings difficult. Diverse diseases,

parasites, and predators are further hazards.

Of course, it’s

hard to say how much of this is inherent to rainforest climates, and how much

is a result of societies from temperate climates trying to apply technology

developed there to a new environment.

Frequent heavy rain

is a challenge for construction and sanitation, but also leaches nutrients from

the soil, making agriculture difficult, but not impossible. Inhabitants often

use “slash-and-burn” farming, clearing an area of land to farm for several

years, then leaving it to regrow while moving to a new location. While this is

sustainable in principle, growing demand for food, in combination

with logging, has led to mass deforestation.

Even when

uncultivated, the high diversity of rainforest life makes them an excellent

source of new edible fruits (including bananas, sugarcane and

possibly papayas) and medicines. They are also the original source of rubber

plants, and much is still grown there.

Tropical Monsoon (Am)

Less than 2

mm/day but more than (100 – [total annual precipitation (mm)] / 25) mm total

rain in the driest month of the year.

Examples: Southwest Indian coasts; Sierra Leone;

Miami, Florida.

Conditions: This zone can be divided into two

subtypes: Areas on the perimeters of rainforest zones that have similar wet and

dry seasons that are somewhat more pronounced; And areas affected by monsoon

wind patterns that have extremely wet summers—sometimes over 30 mm/day—and dry,

sometimes rainless winters (winter months with no rain still satisfy the

requirements if total annual rainfall is over 2,500 mm).

|

| Varandha Ghat, India. Cj. samsom, Wikimedia |

Ecology: Those areas bordering tropical rainforest

are largely indistinguishable from them. Vertical microbiomes are less

distinct, while more pronounced wet and dry seasons may lead to seasonal

flooding. In areas caused by monsoon wind patterns, the severe dry season may

favor woodier plants and vines, but in general the intense summer rains are

sufficient to sustain thick forests.

Society: Once again, largely indistinguishable from

rainforests. Farmers do have to take the seasonal rains into account and avoid

planting crops too early before the wet season.

Tropical Savanna (Aw/As)

Less

than (100 – [total annual precipitation (mm)] / 25) mm total in the

driest month.

Examples: Serengeti; Bangkok, Thailand; Havana, Cuba.

Conditions: As with the monsoon zone, there are two

major subtypes: Regions on the perimeter of large rainforests, with moderate

wet summers and dry winters, and regions affected by monsoon wind patterns that

have very wet summers—sometimes over 10 mm/day—and dry winters. Moving poleward

from the center of the tropical band, the dry season gets progressively longer

and the wet season progressively shorter, especially on west coasts and

interiors that eventually transition to steppes and deserts.

As regions are dry in summer and wet in winter

due to rainshadow effects, but seasonal temperature variation is so low that

this has little practical impact. There is some temperature variation, though:

from around 20 °C in winter to 25 °C in summer.

.jpg) |

| Serengeti, Tanzania. Harvey Barrison, Wkimedia |

Ecology: In spite of the name, this zone is not all

open ground, and indeed it includes a large range of biomes; regions near

rainforest or monsoon zones with short dry seasons will often have similarly

lush forests. Areas with longer and more severe dry seasons will transition to deciduous

forests, that drop their leaves in the dry season to conserve water—this lets

more sunlight reach ground level, causing thicker undergrowth. These forests

have less diversity than rainforests, and individual species have wider ranges.

All life must adapt to long winter droughts. These forests are also more prone

to large fires.

Finally, the driest

areas transition to grassland, savanna (grassland with scattered trees) and

shrubland. Large grazing herbivores and their associated predators and

scavengers are common, many of them migrating long distances to avoid the dry