An Apple Pie From Scratch, Part VIIa: Geology and Landforms: Tectonics and Volcanism

%E2%80%93Valle_Carbajal_01.jpg/1280px-ARG-2016-Aerial-Tierra_del_Fuego_(Ushuaia)%E2%80%93Valle_Carbajal_01.jpg) |

| Valle Carbajal, Argentina. Andrew Shiva, Wikimedia. |

Now that we know about the history and current climate of our planet’s landmasses, it’s time to get down to the work of actually mapping out and committing to final versions of the major landforms. This is a pretty daunting task, and I can easily see the temptation to take shortcuts or gloss over it. But I believe that doing the work to create detailed terrain will pay dividends later on in the form of emergent worldbuilding.

One thing that I hope is becoming clear throughout this series is that we’re not pursuing realism for its own sake; complex factors interacting in complex ways create diversity that’s hard to produce through imagination alone. Rather than making a world with just a single terrain type of “highland interiors, squiggly coastlines”, we’re making a mosaic of different types of mountains, coasts, islands, rivers, and subtler features, which will lend itself to easy creation of diverse ecosystems and cultures later on, with obvious implications for the political and social development of the world. This in particular seems to be a stumbling block for many people starting out; trying to plan out their societies first, and build the geography to fit. What I’m outlining here is a method to build the geography first and let that determine culture through its diverse manifestations.

So: as is becoming the pattern, I’ll approach this subject in two ways. First, I’ll take a conceptual approach, outlining the forces at play in building terrain and how they interact to create specific landforms; Then, I’ll take a practical approach, laying out a methodology for building terrain that takes advantage of a couple software tools to accelerate the process and remove some of the guesswork.

The first two posts will cover the conceptual approach. In this post I’ll describe the major features of terrain created by tectonic forces and volcanism; in each case describing the general form, specific examples on Earth, their typical dimensions, and here and there I’ll add some notes on their ecological and social impact. In the next post, I’ll describe terrain features created by erosion of the surface and transport of eroded sediment, with much the same approach. Each post will necessarily dip a little into the other’s subject matter, but hopefully breaking it up like this will make them each a bit less daunting to get through.

- Tectonics

- Volcanic Terrain

- Volcanoes

- Shield Volcano

- Fissure Vent

- Lava Dome

- Stratovolcano

- Cinder Cone

- Supervolcano

- Large Igneous Province (LIP)

- Other Volcanoes

- Other Volcanic Features

- Regarding Gravity

- In Summary

- Notes

Tectonics

These are features caused by the movement of large sections of the crust. The largest and most obvious features are created by the movement of tectonic plates, and if you followed my tutorial for plate tectonics in Part Va, then you should already have at least a sketch of where these should appear. But tectonic forces can also operate on smaller scales: The forces working at the boundary of plates can cause stresses reaching deep into their interiors, folding or fracturing large regions of the surface without breaking the crust apart entirely. Exactly how and where this alters the terrain is the result of a subtle interplay of materials and stresses, which we can’t realistically predict ourselves. My approach, then, will be to outline general areas where features can appear, and then leave it up to you where to actually place them (I’ll try to demonstrate what that actually looks like in later posts).

Mountains

|

| Aiguille du Midi, French Alps. Martin Janner, Wikimedia. |

Something to bear in mind first: If you look at Earth,

you’ll note that there are two big belts of active mountain-building: One big ring around the shores of the Pacific, heading up the cordilleras on the west coast of the Americas, looping around through the Aleutians and Kamchatka, on through Japan, the Philippines, New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, and New Zealand, then shooting across Antarctica to close the loop; and a spur off that ring in Indonesia, heading northwest up to the Himalayas, then through the Zagros, Carpathians, Alps, to finally terminate in the Atlas (with smaller spurs in Australia, the Caribbean, the Marianas, and elsewhere).

|

| Major "belts" of active orogenies. Underlying map modified from NOAA. |

But like Earth, there will still be older inactive mountains elsewhere in the world, some of them quite substantial. The features I’m describing apply mostly to young, active orogenies. As mountains become inactive and age, they’ll erode down and these features will gradually become less distinct.

Andean-Type Range

|

| Southern Andes. All these topographic map images were made in Google Earth (the desktop version) using this overlay. The dotted white or black lines are just seams in the image tiles. |

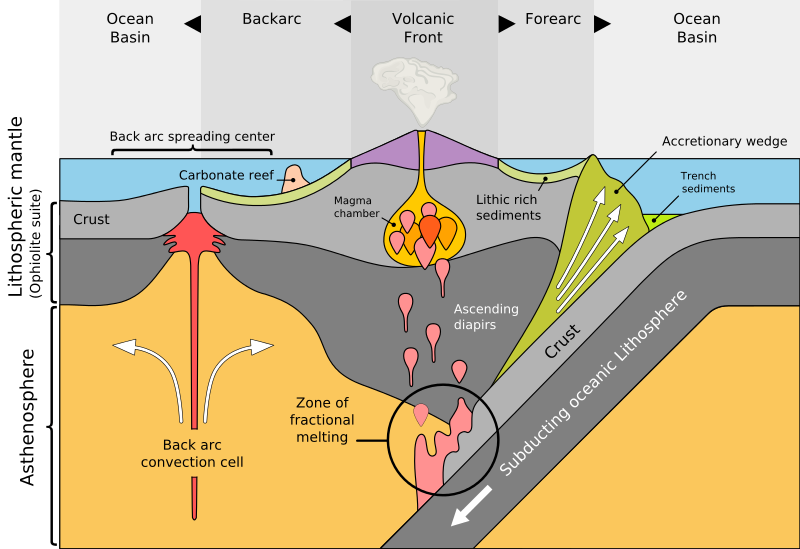

- A volcanic front where main volcanism occurs, containing the highest peaks. This can be a single ridgeline or a broad plateau bracketed by ridges. There may also be multiple parallel ridges due to movement of volcanic activity over time.

- A forearc region between the front and the trench. This often includes an outer-arc ridge along the shore where the land is pushed up by the subducting plate; essentially a lower secondary mountain range without volcanic activity. The relative lowlands between there and the volcanic front are termed the forearc basin.

- A backarc region on the other side of the front, which in some cases is considered to extend all the way to the nearest divergent boundary. There’s typically a clear fall line dividing the steep volcanic front from the flatter backarc, but the backarc may still have a slight incline from the mountains to the coast.

|

| Diagram of a subduction zone and orogeny, showing some of the finer details. MagentaGreen, Wikimedia. |

For young ranges these distinctions are quite clear, but as they age erosion takes hold and there often multiple volcanic pulses creating overlapping ranges, such that both the individual regions and the edges of the range overall become less distinct. The outer-arc ridge in particular is not always present. It’s also fairly common for offshore island arcs to collide with continents on shorelines with Andean-type ranges, and then for subduction and the associated orogeny to resume along the new coastline, ultimately forming a much broader range with multiple ridgelines—such as the Canadian Rockies.

Examples: Andes (South America), Alaska Range (North America), Atlas (northwest Africa), New Guinea Highlands.

Dimensions: The exact dimensions of these features vary, but by looking at examples on Earth I’ve charted out some typical values (All averages; there can be higher individual peaks or unusually sized valleys. Drawing not to scale):

But the mountains themselves can also form a distinct ecological and cultural community, largely because they’re cooler than surrounding areas. It’s common to see high-latitude, cold-climate species living in mountains at progressively higher latitudes closer to the equator, hence the broad rule of thumb that rising 1 kilometer in elevation is roughly equivalent to travelling 5-10° latitude poleward. Mountains can even sometimes allow cold-climate species to cross between continents, possible even from one hemisphere to another.

There are also various mineral resources that may be found in the mountains and their foothills, but that’s a subject I’ll explore in depth another time.

Laramide-Type Range

|

| North American Western Cordillera (primarily the Rockies) |

These are similar to Andean ranges but more extended, with deformation reaching deep into the continent interior. They have the same overall structure but in particular feature a wide plateau in place of the volcanic front, bracketed on both sides by high ridgelines. They’re also generally less volcanically active, though this may vary. The exact formation mechanism is not perfectly understood, but seems to be related to flat-slab subduction (the subducting crust rides under the overlaying plate for some distance before descending into the mantle) due either to (relatively) fast movement of the continent or subduction of a mid-ocean ridge.

Examples: Rockies (North America), central Andes (Peru, South America).

Dimensions: As with the Andean ranges, I’ve charted out typical values for the major features:

Impact: Much of what I’ve said of the Andes will be the same here (and for other mountains), but the broader features do cause subtle differences. A large forearc basin (if it is present) will allow for larger communities to appear on the coastal side (like in California’s Central Valley), and the mountains themselves will be a broad ecological zone with various internal variations in topography. Broader, shallower slopes may also make these actually easier to cross than Andean ranges, but that will depend on the particular age and topography of a given range.

Ural-Type Range

|

| Caucasus Mountains (the dark green area on the right should be the Caspian Sea, but this overlay doesn't show lakes or inland seas) |

The typical result of collisions between major landmasses. They have a much simpler structure than subduction-related ranges; there is a single main ridge, perhaps with some smaller subridges alongside, but no major interior basins (though multiple ranges can form in parallel due to repeated collision events) and typically little or no ongoing volcanism. However, for young mountain ranges the immense weight of the mountains can push down the surrounding crust, forming broad foreland basins along the range’s sides—particularly on the side that was the underlying plate in the subduction that preceded this collision. As the range ages, the mountains erode down (and so the weight decreases) and these basins may be filled in with sediment.

These ranges typically stretch between coasts, dividing two large lowland areas, but if an island arc collides with a continent they’ll form along the coastline, typically with a new Andean orogeny forming next to it. As with subduction orogenies, the boundaries of these mountains—the fall lines—are often quite distinct, but can become less so with age, erosion, and deformation.

Examples: Caucasus (Europe/Asia), Alps (central Europe), Pyrenees (west Europe). Though I’ve taken them as the namesake, the Urals (Russia) are somewhat older and eroded down.

Dimensions: Here, again, are some typical dimensions:

Himalayan-Type Range

|

| Himalayas Mountains and Tibetan Plateau |

These are perhaps the most dramatic forms of mountains, producing the highest peaks (at least on the modern Earth). The one good example we have, the Himalayas, formed after repeated collisions between microcontinents and Eurasia’s south coast—creating a cobweb of fault lines and smaller ranges—and a final collision in which India partially subducted under Eurasia. How much of this is necessary for a Himalayan-type orogeny is hard to say, so I’ve taken “complex, high-speed collision” as my standard for the formation conditions.

|

| India-Asia collision, deforming many preexisting sutures. Raynaldi rji, Wikimedia. |

Much as with Ural-type ranges, there is a single highland area, rising sharply on both sides—though there can be peripheral valleys created by foothills, and the ends are less distinct—but rather than a single ridge it’s a broad plateau, bracketed by ridgelines and with some internal parallel ridges as well. They similarly lack volcanic activity, and once more basins may form along the sides, with very distinct fall lines.

Example: Himalayas (Asia).

Dimensions: It’s hard to generalize from one example, but here’s the typical profile of the Himalayas:

Impact: Little more to say here; these combine the broad internal plateau regions I already mentioned for Laramide-type ranges with the adjoining fertile foreland basins I mentioned for Ural-type ranges.

Foothills

|

| Sun River Canyon and environs, Montana. Qfl247, Wikimedia. |

Returning to continents, the deformation caused by orogenies can extend far beyond the main mountain-building area (especially for the broader Laramide- and Himalayan-types) creating some features that we might still call “mountains” but have very different structures.

Fold-And-Thrust Belt

|

| Appalachian Mountains |

Features formed by compression of the crust in the backarc region of subduction orogenies and to the sides of collision orogenies; Long, parallel ridges with no volcanism and more rounded terrain with few individual peaks. These are formed by the folding of layers of sedimentary rocks as the land is compressed—like the folds that form when you push a rug.

|

| A typical fold-and-thrust belt, in cross-section. Source. |

The folds reach deep into the crust, and will often alternate between harder and softer layers, so they erode down unevenly and the ridgelines may move around but the region retains the same overall appearance and topography. Because of this, and because these often form further from the coast than the main mountain ranges, many of the oldest mountains are fold-and-thrust belts.

Examples: Appalacians (east USA), Zagros (Iran), Arakan (southeast Asia), Cordillera Oriental (Andes foothills, Bolivia).

Dimensions: The ridges are usually 5-50 km apart and up to hundreds of kilometers long, and a typical belt is 10-20 ridges across. The ridges can be over 2000 m in elevation and typically stand 1000 m above their intervening valleys.

Basin and Range

|

| Basin and Range Province |

Features formed by extension, when local or distant forces are working to pull the crust apart. The mechanics

here are a bit more complicated: the extension splits the surface rock into

blocks and some of these blocks will sink down into the mantle while others

remain aloft, creating an alternating pattern of low, long basins called Grabens and high ridgelines called Horsts.

|

| USGS/Gregors, Wikimedia |

Dimensions: Topography is broadly similar to fold-and-thrust belts, but the ridges are shorter—usually under 100 km—less straight and parallel, and less resistant to erosion.

Amorphous Mountains

|

| Anatolia |

All the above categories of mountains—distinct types of orogenies and foothills—apply best to young mountain ranges. As ranges age, deformation shifts, and new features overlap old, they match the ideal cases less and less. As a result, in areas between the major mountain ranges you may sometimes just get large regions that don’t exactly match any of our models and instead just appear as large, oddly-shaped highland plateaus; regions like Mexico, Anatolia, and southeast China.

They still exhibit some general patterns; the edges of the plateaus usually have more distinct ranges and higher peaks than the interiors, there’s a preference for ranges to appear parallel to the plate boundary forming them, and there’s often still a clear fall line, though not as straight and continuous as for younger mountains. Past that, it’s hard to say anything in general about their dimensions.

The point here is just that it’s okay to have some mountainous regions that don’t fit neatly into the above categories. And, like I mentioned, Earth’s mountains often seem to appear along continuous belts, so you can sometimes use these to fill in the space between the more clearly defined ranges.

Island Orogenies

|

| Aogashima, Japan. Charly W. Karl, Flickr. |

Trailing-Edge Island Arc

|

| Japan, Ryuku Islands, and Taiwan |

Andean and Laramide-type orogenies form when subduction occurs on the leading edge of a continent, but when subduction occurs on the trailing edge, the margin of the continent is pulled away from the main landmass by slab rollback (the subducting slab descends strongly and so pulls the subduction zone towards the underlying plate). The result is a chain of islands separated from the continent by a broad, flooded back-arc basin.

Mountain-building still occurs on these islands, but rather messily; the neat regions and distinct ridgelines of Andean-type ranges may be hard to spot, if they’re present at all, and there may be gaps filled with only scattered volcanic islands. Across the back-arc basin, the shore of the continent may have some ridgelines (mostly remnants from before significant slab rollback) and scattered volcanism, but large sections may also be flat, resembling passive margins (coastlines without orogenies)—though sheltered from the open ocean.

Examples: East Asia (Japan, Taiwan), Mediterranean (Corsica, Sardinia).

Dimensions: Small volcanic islands can be only a few kilometers across, but both examples have islands hundreds to thousands of kilometers long and about 100-200 km wide, with central highlands up to 3 km high.

Ocean Island Arc

These have somewhat different features as they age and continue to build up, so I’ve split them into 3 stages of development. Many arcs collide with continents shortly after formation, so the older varieties are progressively rarer:

Young Island Arc

|

| Aleutian Islands |

Island arcs forming within the first 50 million years or so of subduction. These appear mostly as individual rounded islands with volcanic peaks at their centers—essentially just the peaks of submerged stratovolcanoes, though flat areas can form as reefs develop or volcanoes go extinct and erode down. They usually appear as a chain parallel to the subduction zone, but much as with Andean-type ranges, the main front of volcanism can shift over time and so you might have secondary parallel chains with extinct volcanoes (this can also occur due to slab rollback, much as with trailing-edge island arcs).

Examples: Marianas (west Pacific), Aleutian Islands (north Pacific), Solomon Islands (southwest Pacific).

Dimensions: They’re usually 100-300 km from the trench and spaced 20-100 km apart. (sometimes in clusters, and not always along the exact same line). Individual islands are usually around 10-20 km across, though range from under 1 km to over 100 km. Volcanoes are usually around 500 m to 1 km above sea level but can be just barely reaching above sea level or reach to over 2 km above it.

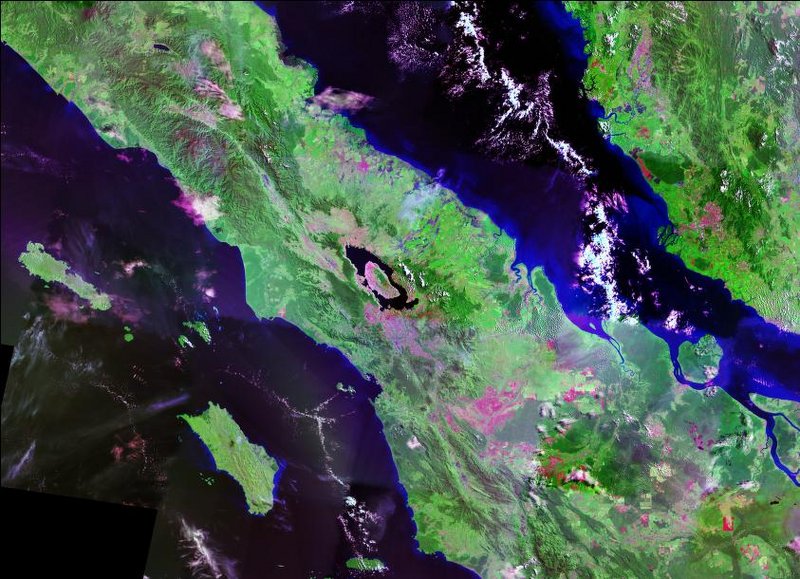

Intermediate Island Arc

|

| Philippine Islands |

Arcs around 100 million years old. By this point successive waves of volcanism have piled up enough rock to form large islands, and erosion of that rock and ash has filled in the areas between and around the volcanoes with broad plains, such that at least some of the islands have transitioned from just volcanic peaks to proper landmasses with a variety of terrains—though there can still be some of the former type of island in the same arc.

Examples: Antilles (Caribbean), Philippines (west Pacific).

Dimensions: Large Islands can be up to 1,000 km long and hundreds of km wide, with mountains peaking at 2-3 km high. But many islands may still be under 50 km across.

Mature Island Arc

|

| Sumatra, Java, and surrounding islands of Indonesia |

Arcs several hundred million years old. The arc is now dominated by a small number of large landmasses, and approaching the point where we could call it a proper continent. Many of the features of Andean-type ranges are now present, in partially submerged forms: A volcanic front forming a continuous range along the coast of the major islands, an outer-arc ridge forming a line of islands offshore with the forearc basin as a shallow sea in between, and the bulk of the islands forming a broad, flat backarc region on the side of the islands facing away from the subduction zone.

Examples: Indonesia (South Asia).

Dimensions: Indonesia contains several islands over 1,000 km long, though they’re not usually more than a couple hundred km wide. Sumatra has a continuous, Andean-like ridgeline roughly 50 km across and over 3 km high at its tallest, but Java still has a more discontinuous line of volcanic peaks.

Other Tectonic Islands

In addition to orogenies, there are a couple other ways that tectonic forces can form islands that may be worth noting.

Microcontinents

Sections of mature continental crust with their own tectonic plates; really these are just small continents, but because they’re small we might call them islands on semantic grounds (in past posts I’ve informally defined the continent/microcontinent distinction by the presence of absence of cratons, but this is a somewhat arbitrary distinction and the definition of “cratons” varies a bit between sources). They aren’t any notable microcontinents with distinct landmasses and their own plates on Earth today, but there have been at several points in the past; during the Triassic, for example, there was a long line of microcontinents stretching across the Tethys Sea to Pangea’s east, and depending on the exact timing and sea level these may have been distinct landmasses or formed one long ribbon continent—a feature that we might dismiss as unrealistic at a glance on fictional maps but has appeared several times in Earth’s past.

|

| Distribution of landmasses to Pangea's east around 230 million years ago. We can't reconstruct the coastlines with much precision; many of these may have been partially submerged. Université de Lausanne. |

Hotspot Islands

|

| Hawaiian Islands |

Islands caused by volcanic hotspots, where magma rises up from the mantle and forms a volcano not directly related to subduction (I’m still counting them as “tectonic” features, even though though they’re not exclusive to plate tectonics). Exactly how hotspots form and the roles played by the mantle, tectonic plates, and even the core are matters of some debate, but broadly speaking they seem to form under 3 conditions:

- Isolated hotspots that can appear anywhere on the planet. There is some evidence that at least some of these may be associated with structures in the lower mantle, such that they should be more common in two broad areas around the center of the prior supercontinent and directly on the other side of the planet. But it’s a weak trend with enough exceptions that for worldbuilding purposes you can treat their distribution as essentially random.

- Plume-related hotspots that appear as clusters either preceding the emergence of a large mantle plume breaks through the surface, as happens during a Large Igneous Province or major continental rifting event, or remaining afterwards when the plume has mostly died down. The degree to which these are actually distinct from isolated hotspots in mechanism is up for debate (the latter may just be smaller, less violent plumes); I distinguish them merely to give some guidance on where they should appear.

- Shallow hotspots, caused not by activity in the mantle but extension of the crust: For example, when slab rollback forms a back-arc basin, this may create weak points in the crust through which magma from the mantle can rise—generally just enough to fill in the gaps with ocean crust, but occasionally proper volcanoes and islands can form. Similar tectonic stresses can also form such hotspots near mid-ocean ridges, plate boundary triple junctions, and even within continents near failed rifts.

When a hotspot appears in the ocean, the resulting volcanoes can form islands much as those of young subduction zones do. They’re not quite the same, though, as hotspots tend to form shield volcanoes instead of the stratovolcanoes of subduction zone island arcs. We’ll discuss the distinction more later, but in short hotspot islands will tend to be broader, with shallower slopes, and covered with more volcanic rock as opposed to ash (though mature islands should have plenty of sediment from erosion).

|

| Formation of new islands over a hotspot as the crust moves. |

At any rate, the result is a chain of islands leading away from the hotspot in the opposite direction of the plate’s motion. Only the youngest islands nearest the hotspot are volcanically active; those further from the hotspot are progressively older and more eroded down, and even past the end of the chain are a long line of seamounts that may once have been islands but have long since eroded down.

That is the ideal case, anyway; hotspots can vary in

activity, and may sometimes actually move on their own (rather than just

appearing to move relative to the crust), such that rather than a neat chain

they may form scattered clusters of islands.

Iceland is also an unusual case; how it formed is debated, but for now the

leading theory is that it may be the result of a mid-ocean ridge happening to

move over a cluster of plume-related hotspots. Whether such a large island will

form whenever mid-ocean ridges encounter hotspots—and in particular whether it

can happen with isolated hotspots—is not clear; other hotspots (e.g. the New England hotspot)

appear to have moved across mid-ocean ridges without creating large islands,

but they may have just been inactive at the time. Still, you can perhaps bear

it in mind as an option to get an isolated island with unique terrain.

In case you're wondering, when a hotspot appears on land it can also create a string of volcanoes, but tends to create broader plateaus rather than a string of distinct peaks; much of the highlands in the central Saharra are hotspot-related.

Examples: Isolated: Hawaii (central Pacific); Plume-related: Maldives/Reunion (Indian ocean), Iceland (north Atlantic); Shallow: Hainan (Chinese coast). There are also some ambiguous hotspots that appear to have multiple influences such as the Azores (east Atlantic) and Galapogos (east Pacific).

Dimensions: Hawaii’s youngest peaks reach 1-4 km above sea level and form islands 50-150 km across, spaced roughly 100 km apart. The most prominent part of the chain is roughly 600 km long, but seamounts and atolls stretch for another 5,000 km beyond that. Other hotspot islands are generally around the same size, but vary in number and activity; less active hotspots may only occasionally form single islands (e.g. Reunion), while more active ones may form 5-10 major peaks that are simultaneously active and appear in a cluster rather than a chain.

Ophiolite

These are sections of oceanic crust that have been uplifted on top of a continental margin. Exactly why this happens isn’t clear, but it appears to be related to a collision that closes a subduction zone: Some section of the oceanic crust of the overlaying plate may remain when subduction ceases, and further compression will uplift it above sea level. Usually the ophiolite is pushed onto a coastline shortly afterwards, but Cyprus is formed from a young ophiolite, and so you can perhaps expect similar islands to form within closing oceans.

Other Tectonic Features

To round this section off, here a couple final features that result from the motion of tectonic plates, but don’t neatly fit into any of the previously discussed categories.

Continental Rift

|

| East African Rift (several of the flat areas are filled with lakes that are, again, not shown in this overlay). |

These are young divergent boundaries, or failed rifts

branching out from them (a large hotspot island like Iceland that forms

directly above divergent boundary will also have some of these features).

Divergent boundaries will eventually pull continents apart and form new oceans

between them, and failed rifts will decline in activity, but before this

happens there will be a period of volcanism and extension along the rift.

Contrary to popular depictions, the rift itself is not a thin canyon with steep

walls to either side; individual faults may sometimes appear like this, but the

rift as a whole will contain many faults, some obvious and some more subtle,

often in parallel such that there are sections of land in between not clearly

on either side of the rift. Instead the rift will form a broad rift valley. Sections of rock to either

side of the valley will subside in sections, such that the valley appears to

have a stepped structure in cross-section, with alternately steep and shallow

slopes—though sheer cliffs are still uncommon.

Much as there are parallel faults within each valley, there can also be parallel rift valleys as much as hundreds of kilometers apart. For a successful rift, one of these will eventually emerge as the final divergent boundary, with the others becoming failed rifts (though they can still spread enough to create “failed microcontinents” like we mentioned before).

| Rift valleys (bracketed by dotted lines) and volcanoes (red triangles) in East Africa. USGS. |

But the rift also causes volcanic activity, mostly in the rift—and especially

near triple junctions—but also in scattered spots around it. This may sometimes

produce enough volcanic rock to fill in a section of the rift valley, but

continued spreading will push this rock to the side, such that once volcanism

dies down the rift valley will reappear, flanked by ridges of volcanic rock, that can be comparable in scale to the mountain ranges we discussed earlier (though generally not quite as continuous, long, or steep).

Examples: The East African Rift is the only known major, active rift associated with a divergent boundary—though its eventual success in splitting the African plate apart remains to be seen. The Baikal Rift (Russia) and New Madrid Fault (USA) are failed rifts that have been reactivated to different extents by tectonic stresses (active volcanism and spreading for the former, occasional faulting and earthquakes for the latter), though neither will form divergent boundaries.

Dimensions: The East African Rift stretches over 3,000 km long, consisting of several distinct valleys. I’ve put together a typical profile here, much like with the mountain ranges:

Impact: Perhaps the most important impact of rifts is the lakes and rivers they create. East Africa is largely dry savanna, but the rift valley contains patches of forest. It may have even provided a refuge for our own ancestors in periods of drier climate, as well as other wildlife in the region. As a rift widens and a continuous channel begins to form, they may allow for travel by ship, and remaining land bridges may become strategic choke points.Fault

|

| Great Glenn Fault, bisecting the Scottish Highlands |

Faults are breaks between rocks, allowing two sections of rock to move relative to each other. These appear at all scales from pebbles to continents, and all the tectonic features we’ve discussed will create vast networks of faults at various orientations. But here I’m specifically concerned with large transverse faults, where two large sections of land are moving past each other in opposite directions (or moving in the same direction at different rates). The largest of these occur on plate boundaries, but they can also form within plates when large sections of surface rock are moved by tectonic forces. For example, complex collision events can often form faults even far from the plate boundary.

This has two obvious effects: For one, preexisting surface features will be broken and displaced, in some cases placing mountains directly next to lowlands with a straight boundary between them. The zigzag shape of Scotland’s coasts, for example, is caused in part by displacement of the mountains by faults. Secondly, the fault grinds rock and creates a weak point in the surface which will erode down, and so long, thin valleys will often form along the fault line.

Examples: San Andreas Fault (western North America), Great Glenn (Scotland; inactive), Alpine Fault (New Zealand), Jordan Rift Valley (Middle East).

Dimensions: Up to over 1,000 km long, with areas on either side displaced by up to hundreds of kilometers. Valleys formed are usually under 10 km across, though.

Impact: Active faults can cause devastating earthquakes, but dormant faults can be a boon to the region: they can form large passes through mountains, and often water will gather in the fault and create lakes and rivers, aiding travel and possibly creating a sort of oasis in dry regions.

Fault-Block Terrain

Terrain formed under extension, forming alternate low grabens and high horsts (due to the formation of distinct blocks of crust separated by faults, hence the name). We've already discussed basin and range mountains (and rift valleys, which are essentially large grabens) but horsts and grabens can form at much smaller scale as well, and individual grabens can form in isolation. The extension that causes them doesn’t only occur from lateral movement of the surface; uplift of highland regions can stretch and fracture the surrounding rock, much as rising bread will form cracks in its surface.On Earth these can never get too large, as enough extension will eventually just rift plates apart, but they can get much bigger on stagnant-lid worlds; the Valles Marineris on Mars appear to have formed this way, as the rise of the Tharsis highlands tugged on the surrounding crust.

Uplift

Orogenies and similar tectonic events tend to form concentrated mountain ranges that only occupy a small part of the involved landmasses, but the same forces can also push up broad regions, even entire continents. To be clear, I’m not referring to the creation of highlands by piling more material on top of the crust, or lateral compression of small areas of it; in these cases, whole regions of the crust are being pushed up from below. Exactly why and when this happens isn’t always totally clear but there are a few patterns:

Most orogenies cause little uplift outside the range itself, though the associated compression may cause distant folding of the crust. But in North America, the formation of the Rockies has uplifted much of the surrounding region, such that there is a shallow gradient across the middle of the continent from the Mississippi Valley near sea level to the base of the mountains at 1 kilometer or more elevation. We might expect similarly broad Laramide-type orogenies to do the same elsewhere.

LIPs and continental rifts also seem to cause uplift: Much of eastern and southern Africa has been uplifted by over a kilometer by the same plume of hot rock that is causing the East African rift. Many coastal areas of the Atlantic have also experienced recent uplift despite lying on passive margins, and our best guess is that this is due in some part to the same upwelling of hot rock that split Pangea apart in the first place; so we may see similar uplift in other cases where a supercontinent has recently split apart.

At first, broad uplift of this type will create a high plateau, essentially just lifting up the preexisting flat plains. As time passes the sediment will erode away, but the previously buried roots of an ancient mountain range may better resist erosion, and so remain as highlands once the rest of the uplifted material has eroded away. Thus, a mountain range can be eroded completely flat, and then later revived by uplift and erosion. This appears to be the case with the Appalacians, for example, possibly in relation to the orogenies on the west coast, or possibly due to the aforementioned upwelling of the mantle around the former core of Pangea.

|

| Formation of a mountain range, erosion, and exhumation by uplift. |

And finally, uplift can occur after the retreat of large glaciers. We’ll discuss the implications of this later, but in short the weight of these glaciers can push down the crust, like mountains, and once the glaciers retreat the crust will slowly rise back up. Some areas may have risen by several hundred meters since the last glacial maximum.

Impact Crater

|

| Barringer Crater, Arizona. USGS. |

Structures formed when a solid body (a meteorite, asteroid, or comet) strikes the surface. Calling these tectonic features is a stretch, but frankly there’s no other good category for them.

|

| Elongated crater on Mars. NASA/JPL-Caltech/Arizona State University. |

The initial explosion pushes out the rock to all sides, and lifts much of it in the air; larger pieces of ejecta may eventually fall back to the surface up to thousands of kilometers away and form their own impact craters, and some may be ejected at escape velocity and escape into interplanetary or potentially even interstellar space. But most is thrown a short distance and falls around the edges of the impact, forming a ridge around the crater rim. After the initial explosion, the walls of the crater collapse inward, filling the interior with debris. For relatively small impacts, the result is a simple crater, with a bowl-shaped depression that reaches its lowest point at the center.

|

| Cross-sectional structure of typical impact craters. NASA. |

But for larger impacts, the rebound of the ground after

being pushed out after the explosion can ultimately push up sections of the

crater floor, forming a complex crater. Small complex craters form a

single peak at the center, larger ones form a ring of high ground, and huge

craters can form several concentric rings.

|

| Craters on the moon of increasing size and complexity. Left to right: Biot (13 km diameter); Tycho (86 km); Schrödinger (312 km); Mare Orientale (900 km). All from NASA. |

Large impacts can also melt enough of the surrounding rock to fill in the crater floor with lava, which cools to form a layer of volcanic rock. Some geologists have speculated that large impacts may create volcanic hotspots by weakening the crust—either at the impact site, or at the exact other side of the world where shockwaves from the impact coalesce—but so far no volcano, active or extinct, has been clearly linked to an impact event.

Examples: Barringer Crater (Arizona, USA), Clearwater Lakes (Canada), Lake Manicouagan (Canada), numerous on the Moon, Mars, and other geologically inactive solar system bodies.

Dimensions: On Earth, simple craters can be up to about 4 km across (though there are also complex craters as little as 2 km across, due to variations in the strength of the bedrock), but in the lower gravity of the Moon they can be up to about 20 km across. Complex craters on the moon transition from peaks to rings at about 175 km across, and then to concentric rings at about 500 km. Presuming similar scaling as for simple craters, that would imply the same transitions should occur on Earth at about 35 km and 100 km (there are craters over 35 km across on Earth, but they’re generally too old and eroded for their original structure to be clear).

The same rebounding that uplifts the center of a large crater—along with filling of large crater floors by lava—also tends to limit their depth to a few kilometers. Even the enormous Hellas Planitia on Mars, over 2,000 kilometers across, is only 7 km deep and mostly flat on its floor.

Impact: The social and ecological impact of an impact event is a subject for another time, but existing impact craters are notable mostly just as odd lakes or steep-walled depressions. Occasionally the lava formed by a large impact may cool to form valuable ores, such as the nickel and copper ores in the Sudbury Basin.

Otherwise, more than a few sci fi authors have speculated that craters on the moon or Mars might make convenient sites for domed cities, with the edges of the dome secured along the crater rim, the floor covered in soil and then vegetation or buildings, and perhaps a lake forming in the center.

Volcanic Terrain

Now that we’ve covered large-scale processes that build

continents, mountains, and islands, let’s take a quick detour to describe the

small-scale features of terrain with ongoing or recent volcanic activity. Most

of these features are pretty quickly destroyed by erosion on geological

timescales, so they aren’t too common on Earth today, but there are still a few

areas where they dominate.

Volcanism is, of course, the result of magma, often originating in the mantle,

rising through the crust. A lot of magma actually never reaches the surface,

cooling underground and forming various plutonic features that may later

be exhumed by uplift and erosion. But here we’re concerned with volcanic

activity on the surface, which we can broadly divide into two major types:

- Effusive Volcanism, wherein magma simply breaks through the surface and flows out across the surrounding landscape until it cools enough to solidify. Eruptions are typically frequent but sedate, forming mostly basalt and other mafic (dark, iron/magnesium-rich) rocks.

-

Explosive Volcanism, which is a bit more dramatic; in this case the

rising magma contains water or other volatiles. Whilst deep underground the

superheated volatiles are kept liquid by high pressure, but on reaching the

surface the pressure declines and they transition to gasses, expanding with

such force that they can blow entire mountains apart. Much of the magma is

scattered as droplets in the air, rapidly cooling to form particles of ash or

larger pyroclasts, fragments of rock

often with air pockets and sharp edges. Eruption rates vary, in some cases

being very infrequent but extremely powerful, and form mostly ash and

pyroclasts but sometimes also felsic

(light, silica/alkali/aluminum-rich) rocks.

Generally speaking, divergent plate boundaries and hotspots tend to cause effusive volcanism and convergent boundaries with subduction zones tend to cause explosive volcanism (because magma rising from the mantle is fairly dry, but magma formed by partial melting of subducting crust contains volatiles that were trapped in seafloor sediment), but they don’t do so exclusively and so volcanic regions—even individual volcanoes—often show a mix of effusive and explosive activity.

Volcanoes

|

| Mount Nyiragongo, D.R. Congo. Niel Wetmore, MONUSCO. |

These are all broad categorizations, but there are plenty of ambiguous cases; volcanoes of one type that display some qualities of another type, volcanoes that switch type over their lifetime (even beyond the typical cases mentioned), etc.

Shield Volcano

|

| Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa, Hawaii. Mds08011, Wikimedia. |

|

| Lava flow at Kilauea, Hawaii. USGS. |

Dimensions: Mauna Loa in Hawaii is over 100 km across and 9km tall from its base (4 km tall from sea level). But most shield volcanoes are around 5 km across and under 1 km high. Slopes are typically 2-10°, becoming gradually steeper towards the summit. Olympus Mons on Mars is also a shield volcano, stretching 600 km across and reaching 26 km above the surrounding plains, though this is only possible due to Mars’s thicker crust and stagnant-lid tectonics. Venus’s shield volcanoes are similarly hundreds of kilometers across, but only up to 5 km high.

Impact: Near-constant volcanic activity makes the peaks of these fairly barren and unattractive for settlement. But the flatter, calmer outlying regions can be lusher and more frequently settled, especially where a shield volcano forms an island. Nowadays active but sedate shield volcanoes—especially those with lava lakes—can become tourist attractions. They’re also often used for astronomical and meteorological research, as they’re high points that are reasonably accessible but free from interference from nearby population centers or wildlife.

Fissure Vent

|

| Fagradalsfjall, Iceland. Almannavarnadeild ríkislögreglustjóra, Wikimedia. |

Vents are usually fairly short-lived; sustained activity results in plugging of most of the fissure with lava, with magma flow consolidating into one or a few volcanic cones (often called spatter cones if they remain mostly effusive, though in some cases cinder cones may form instead). These cones may eventually develop into longer-lived shield volcanoes or stratovolcanoes. Otherwise a single fissure usually erupts only once, but multiple parallel fissures may form in one area, gradually building up a plateau of volcanic rock without forming a crater like a shield volcano. Individual extinct fissures may appear either as a row of eroding cones, or a canyon flanked by ridges of volcanic rocks; often both may appear along one fissure.

|

| Spatter cone at Kilauea, Hawaii. USGS. |

Dimensions: Usually a few meters wide and kilometers

long. The catastrophic Laki eruption in Iceland occurred along a vent 25 km

long and formed cones hundreds of meter high.

Impact: Fissure events can appear suddenly and with little warning,

making them very hazardous to nearby communities. In 1973 a vent abruptly appeared

within a kilometer of the town of Heimaey, Iceland;

a rapid evacuation prevented any deaths, but roughly half the town’s buildings

were destroyed by fires, debris, and burial under ash. More severely, the 1783

eruption at Laki produced millions of tons of fluorine gas that killed most of Iceland’s

livestock, resulting in a famine that killed a quarter of the human population;

for a brief period, the then-ruling Danish government considered completely

evacuating and abandoning the island.

Even when the results aren’t so severe, the fast-flowing lava flows produced by

fissure vents can threaten towns downhill, though often earthwork barriers can

redirect them to some extent.

Lava Dome

|

| Chaitén, Chile. Sam Beebe, Wikimedia. |

Another type of effusive volcano, but one more typically formed near subduction zones. They’re fed by more volatile-rich magma, but so long as it can keep flowing out the pressure of vaporizing gasses is never too high, so it does not erupt explosively. However the lava is more viscous, and so instead of flowing out to form a broad shield volcano, it piles up into a steep dome.

Eventually the dome will plug the vent, but magma may

continue to flow into the interior and push out the outer walls of the dome

from inside without breaching them, save perhaps for some small vents producing

small amounts of ash, pyroclasts, and lava. This builds up quite a lot of

pressure, such that if there is a major breach into the interior, the material

there will usually escape in an explosive eruption, producing a stratovolcano

as discussed below.

But there are still young lava domes today that haven’t reached this stage, and

some lava domes go extinct before this point, leaving domes of felsic rock that

are gradually eroded down and covered in sediment.

Examples: Most existing lava domes are temporary structures in the calderas of stratovolcanoes, like at Mt. St. Helens (Washington, USA), or La Soufrière (Montserrat, Caribbean). There are a few active pre-stratovolcano lava domes such as Lassen Peak (California, USA), and various extinct lava domes such as Black Butte (California, USA) and Puy de Dôme (France).

Dimensions: Typically a few hundred meters but up to several kilometers high, and often about as wide, though depending on their history there can sometimes be many lava domes in one area forming an irregular cluster of hills.

Impact: Essentially the same as stratovolcanoes, discussed below.

Stratovolcano

|

| Mount Fuji, Japan. 名古屋太郎, Wikimedia. |

Most of the explosive phases are striking but mostly contained to the mountain itself. But as the volcano grows, the pressure it can contain tends to increase. Should a particular large, robust cap of rock form over the vent, pressure can continue to build up for centuries. When the cap finally is breached, the release of pressure allows some of the volatiles in the trapped magma to vaporize, which opens the breach further, which allows the pressure to drop further, and so on in a chain reaction that can reach all the way to the magma chamber. The resulting explosion can be so energetic (in some cases, releasing more energy than the largest nuclear bombs ever tested) as to essentially blow the top of the mountain off, what we call a “Plinian eruption” (after Pliny the Younger’s description of Vesuvias erupting).

Such an eruption can last anywhere from hours to months, throwing a plume of ash tens of kilometers in the air and bombarding the surrounding region with debris. Worse yet, some of the gas and rock thrown up into the plume may cool enough to suddenly collapse back down, flowing down the side of the volcano as a pyroclastic flow, a mass of gas, steam, ash, and rock still several hundred °C travelling at up to several hundred kilometers/hour, flattening trees and structures and incinerating any flammable material.

|

| Pyroclastic flows at Mayon Volcano, Philippines. C.G. Newhall, USGS. |

Often after such an eruption, the release of pressure causes the magma chamber to collapse and the overlaying ground with it, forming a caldera—a round, steep-walled depression—where the peak of the mountain used to be (other, less dramatic eruptions can sometimes form calderas as well, even for typically effusive volcanoes). The stratovolcano then begins forming a new peak inside the volcano, resuming its usual cycle of effusive and explosive activity.

|

| Formation of a caldera. USGS. |

Examples: Mt. Fuji (Japan), Vesuvias (Italy), Mt. Etna (Italy), Mt. St. Helens (Washington, USA). These are among the most common type of volcano, and also generally long-lived.

Dimensions: The image that pops into your head when you hear the word “volcano” is probably a stratovolcano. They’re typically steep cones, up to 5 km or more high with slopes of around 30° near the peak, topped by a crater a few hundred meters across. After magma chamber collapse, the caldera formed can be kilometers wide, in some cases removing just the peak of the mountain, and in others leaving only fragments of the original mountain as low ridges. Resumed activity usually forms a lava dome at first in the center of the caldera (charmingly called a wizard island if a lake has formed in the caldera), eventually growing to refill the caldera and possible even outgrow the original mountain.

Impact: Pretty all of the famous catastrophic eruptions in history—Vesuvias in 79 CE, Krakatoa in 1883, Mt. Pinatubo in 1991—were Plinian or similar eruptions caused by Stratovolcanoes. These eruptions can occur after centuries of dormancy, and the fertile ash encourages settlement on the flanks of the volcano. Pyroclastic flows are particularly deadly, in some cases killing thousands of people in the space of minutes.

And beyond the local impact, the ash plume created by the eruption can reach into the upper atmosphere and spread across the world, reflecting away sunlight and reducing global temperatures in the worst cases. The 1815 eruption of Tambora led to a global temperature decrease of about 0.5 °C in the following year, but the effect was amplified at higher latitudes, producing the “Year Without A Summer”, with widespread famines and a noticeably orange-tinted sky.

But when stratovolcanoes aren’t causing local or global disasters, the ash-covered region around them does make for quite good farmland, so there is some tendency for large population centers to appear near dormant volcanoes.

Cinder Cone

|

| Paricutín, Mexico. NOAA. |

Individual cinder cones can continue erupting for years, and a few can remain active for centuries, but many erupt only once. Shield volcanoes and stratovolcanoes often form many short-lived cinder cones on their flanks and in the surrounding area.

Examples: Parícutin (Mexico), Lava Butte (Oregon, USA), Mt. Fox (Queensland, Australia). Cinder cones have also been found on Mars, and possibly on the Moon.

Dimensions: Typically tens to hundreds of meters

high, with very circular footprints and straight slopes of 30-40°. Cinder cones on Mars are notably

wider and shallower, as debris is more broadly distributed in the low gravity

and air pressure.

Impact: Though dangerous up close, cinder cones don’t produce large

plumes of ash or pyroclastic flows like stratovolcanoes. Like fissure vents,

they can appear abruptly; Parícutin famously appeared in 1943 in the middle of

a cornfield, and then grew to several hundred meters over 9 years of continuous

activity. The lava flow produced at the end of the eruption can also be a

hazard, much as with fissure vents.

Supervolcano

|

| Satellite image of Toba, Indonesia. NASA. |

Especially large volcanoes formed when a magma chamber forms but cannot breach the surface. Pressure continuously builds up within the chamber until the magma finally erupts through the surface in a manner similar to Plinian eruptions: a large plume of ash is pushed up into the atmosphere, and sections will collapse to flow over the surrounding landscape, and when enough pressure is released the magma chamber will collapse and form a caldera on the surface. What distinguishes them is the scale of the eruption: Large Plinian eruptions may eject tens to hundreds of cubic kilometers of rock and ash, but supervolcanoes produce thousands.

But because of their scale, these eruptions are very infrequent; it may take hundreds of thousands of years of pressure buildup to cause one eruption.

Examples: Yellowstone (Wyoming, USA), Toba (Sumatra, Indonesia).

Dimensions: Without regular, small eruptions, no volcanic cone is formed. Instead, each eruption produces a shallow caldera tens to hundreds of kilometers across, which may host a lake. Each eruption may produce a different caldera, so often a mature supervolcano will have multiple overlapping calderas on the surface, and the overall shape may not be obvious without careful surveying.

Impact: A supervolcano can have widespread, even global impact, though some of what has been said about them is overstating the case; an eruption will not destroy entire continents, nor completely bury them in ash (though some ash will be deposited over a very broad region). Most of the danger comes from the ash placed in the upper atmosphere, which can cause a drop in global temperatures by several °C for years or decades. An eruption today would almost certainly cause food shortages and possibly famines across much of the globe, and were one to happen to a premodern world it could conceivably lead to the collapse of whole societies and significantly impact their social, technological, and economic development. However, past eruptions haven’t been associated with extinction events, indicating the impact isn’t severe enough to wipe out ecosystems, and the effect on climate may vary in different regions.

Large Igneous Province (LIP)

|

| Putorana Plateau, part of the Siberian Traps, Russia. jxandreani, Wikimedia. |

Models for the formation vary, but it’s generally believe LIPs are caused by plumes of hot rock rising through the mantle and then breaching through the crust through many fissures and vents across an area of millions of square kilometers. This is broadly similar to how some hotspots are believed to form, and—as mentioned before—some modern hotspots may either be the forerunners or remnants of LIPs. These plumes may also form as part of supercontinent breakup, and indeed many of the largest LIPs on record are associated with the breakup of Pangea—including the CAMP, which formed directly on the rift between Africa/Europe and the Americas as they were starting to divide.

|

| Extent of the CAMP in Pangea. Williamborg, Wikimedia. |

Over time, repeated lava flows will build up a plateau of mafic rock, which may still remain for millions of years thereafter.

Examples: Siberian Traps (Russia, 250 million years ago), Deccan Traps (India, 66 mya), Central Atlantic Magmatic Province (“CAMP”, shores of the Atlantic, 198 mya).

Dimensions: Hundreds of thousands to millions of km2 in area, with plateaus hundreds of meters or even kilometers high forming in the area of most intense volcanism.

Impact: I’ll discuss the mass extinctions associated with LIPs (in particular the end-Permian and end-Triassic extinctions) another time, but in short they combine basically all of the worst aspects of individual volcanoes, but at mass scale: Lava flows would devastate the regions around the LIP, and ash distributed in the upper atmosphere cools the planet for hundreds to thousands of years. But the worst LIPs seem to cause back-and-forth swings in climate: The initial eruption produces ash, which causes cooling, but they also produce CO2 and methane, which cause rapid warming once the ash has settled—but then the volcanic rock produced begins to weather and draw down CO2, causing cooling again. But not all LIPs cause mass extinctions, so they can occur without such devastating climate impacts.

Still, volcanic activity will vary, and the entire LIP could pass through dormant phases of thousands of years. Any one spot may pass through cycles of devastating volcanism, and then relatively quiet periods when wildlife can return. One can imagine much the same might happen were an intelligent society living through such an event, settling a seemingly hospitable region only to have to contend with a volcanic cataclysm later on.

Today, we have enough data about the Earth’s interior to be reasonably sure that there will be no LIPs in the foreseeable future. I’m not too sure exactly how much warning we would expect to have for such an event, but don’t let that stop anyone wondering what might happen if we were to, say, suddenly learn that such a cataclysmic event were to start in a few hundred years.

Other Volcanoes

To wrap things up, a couple other less common or notable

types of volcanoes:

Pyroclastic shields are rare forms that have broad, shallow slopes like

shield volcanoes, but are composed mostly of ash and pyroclasts like cinder

cones and stratovolcanoes. They appear to be less prone to large Plinian

eruptions.

Tuff cones and tuff rings are piles of mostly ash sometimes formed when magma meets groundwater or a shallow lake or sea. They are broadly similar to cinder cones in size and shape, but composed of finer material and their eruptions don’t usually end with lava flows.

Where an eruption occurs under a glacier, a couple different kind of volcanoes will result. For a small eruption, the lava will remain confined under the glacier and form a subglacial mound: a small, rounded cone of volcanic rock that may remain after the glacier retreats. For a larger eruption, the lava may breach the glacier and flow out the top, but still remain confined by the glacier along the sides, forming a tuya: a regular volcanic cone atop a steep-walled plateau. In either case, such an eruption can melt much of the glacier water, potentially creating a jökulhlaup: a flashflood caused by meltwater suddenly bursting out the sides or top of the glacier.

|

| Pyramid Mountain, Canada, a subglacial mound (left, Uli Harder) and Herðubreið, Iceland, a tuya (right, Icemuon) |

Mud volcanoes are a sort of pseudovolcano, formed not by lava but hot mud and water erupting from beneath the surface. Usually this is due to geothermal heating of subsurface aquifers in volcanically active areas, but mud volcanoes can also form in volcanically inactive areas due to rapid deposition of sediment, which traps pockets of water under increasing pressure until it bursts through to the surface. Most mud volcanoes are no more than a few meters high, but they can become comparably large to “true” volcanoes, stretching hundreds of meters high and kilometers across.

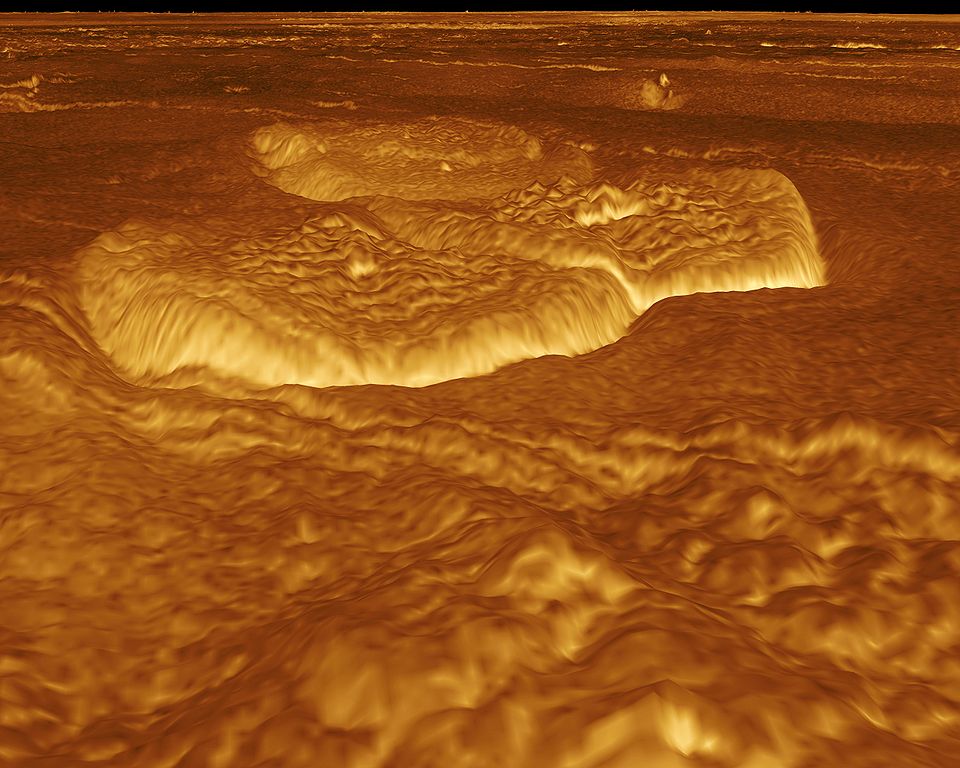

Pancake domes are not known to occur on Earth, but have been seen on Venus. They are broad, circular, falt-topped structures, likely formed by a single outpouring of lava, which could flow much further before cooling thanks to Venus’s hot surface.

|

| Render of pancake domes on Venus based on radar data. NASA. |

Cryovolcanoes are another type of extraterrestrial volcano, formed not by magma rising through rock but instead liquid volatiles (water, ammonia, methane, nitrogen) rising through ice. Their causes and behavior are, in many ways, similar to our volcanoes; tall plumes of steam and ice have been seen on Enceladus, conical structures and calderas have been seen on Titan, and some of the surface of Triton appears to be covered by ice formed from “cryolava” that has flowed out from a vent and then cooled.

Other Volcanic Features

Lava Field

|

| Young lava field (with cinder cone in background) at Krafla, Iceland. Denkhenk, Wikimedia. |

A broad, flat expanse of volcanic rock, formed after lava has flown out across existing flatlands and then cooled and solidified. Young lava fields are often covered in piles of sharp rock and may have deep chasms, making them essentially impassible without heavy equipment. But later erosion and faulting may clear away this layer and reveal underlying columnar jointing: a striking feature where closely spaced fractures formed in the final stages of cooling may form a regular pattern, often hexagonal columns. Further erosion will tend to break away whole columns at once, so often the edge of an old, exposed lava field will form a low cliff.

|

| Columnar jointing at Giant's Causeway, Northern Ireland, from a lava flow 50 million years ago. Jim, flickr. |

Examples: Giant’s Causeway (Northern Ireland), Hell’s Half Acre (Idaho, USA), numerous on Reykjanes Peninsula (Iceland).

Dimensions: Collections of lava fields from sustained volcanic activity can be hundreds of thousands of square kilometers in area, but more typically they’re in the range of tens to thousands of km2. Exposed columnar jointing may often only be clearly exposed in a small area, with individual columns centimeters to meters across and up to tens of meters tall.

Impact: As mentioned, a young lava field can be a barrier to travel in volcanic regions. Older lava fields are notable mostly either for the escarpments around their edges or, if the columnar jointing is particularly pristine and regular, as tourist attractions.

Volcanic Plug

|

| Shiprock, New Mexico. Bowie Snodgrass, Wikimedia. |

Examples: Devil’s Tower (Wyoming, USA), Shiprock (New Mexico, USA), Arthur’s Seat (Scotland).

Dimensions: Tens to hundreds of meters high, with very steep, sometimes even near-vertical slopes, though in some cases enough sediment has piled along the sides to form a more moderate hill. They can be completely isolated in otherwise flat plains, though often multiple will appear in the same region.

Impact: An isolated hill with steep walls naturally lends itself to placement of a fortification, watchtower, or monastery—presuming workers and construction material can reach their peaks. If you need a premodern setting with striking imagery, a volcanic plug is a pretty good bet.

Lava Tube

|

| Kazamura Cave, Hawaii. Dave Bunnell, Wikimedia. |

Examples: Surtshellir (Iceland), Kazamura Cave (Hawaii)

Dimensions: Lava tubes on Earth are up to 30 meters wide and 60 km long, though often much smaller. Most are within a few meters of the surface, but some can extend to kilometers deep. The lower gravity on Mars and the Moon may allow them to have lava tubes hundreds of meters across.

Impact: On Earth, lava tubes are mostly regarded as curiosities, and perhaps occasional shelters. But many discussions of future colonization of Mars or the Moon has identified them as ideal sites for first colonies, providing convenient shelter from solar radiation. In time, a lava tube could even be sealed in and filled with a breathable atmosphere to form a large living area. Some researchers have even speculated that natural isolated lava tubes filled with water or gasses may serve as refuges for life on Mars today.

Hot Spring

|

| Grand Prismatic Spring, Wyoming. Jim Peako, National Park Service. |

Spring of geothermally heated water emerging from underground in regions with volcanic activity. Often these form streams of warm, mineral-rich water, creating islands of life when they emerge in otherwise barren or cold areas. Many hot springs are known for their multicolored appearance due to mats of microbes or staining of the surrounding rock. People have also taken advantage of them, building bathhouses and saunas fed by them or tapping underground aquifers to create their own hotsprings in volcanic areas.

But in some cases a hot spring may form a geyser, which regularly shoots forth violent sprays of water. This occurs when water gathers in a cavern with a source of geothermal heat; water will gather in the cavern, gradually warm until it boils, and the steam produced will shoot through a vent towards the surface, clearing the cavern of water and restarting the cycle. If the sources of water and heat are reliable, the cycle may be so regular that eruptions of steam can be predicted to the minute.

Regarding Gravity

You may have noticed that, throughout this post, I’ve mostly been listing off dimensions of features as they appear on Earth, though in a few cases I’ve referenced analagous features on other solar system bodies, and noted that those features on bodies with lower gravity and thicker crusts are often larger than those on Earth. But for most of the tectonic features we’ve discussed, there are no analogues elsewhere in the solar system—Earth is the only known body with plate tectonics—so we can’t empirically compare their scale under different gravities. Should we still expect them to be larger on planets with lower gravity?

Geophycists have long known that topography across the solar system tends to follow Kaula’s rule: all else being equal, topographic features will tend to scale in their linear dimensions by 1/[surface gravity]2 (at least for bodies above a couple hundred kilometers across). So, for example, an Earthlike world with half the surface gravity should tend to have topographic features about 4 times as tall and wide; and a world with twice the gravity will have features 1/4 as tall. Perhaps the clearest example of this is lava tubes, which form under very similar conditions on Earth, Mars, and the Moon; Mars has roughly 1/3 the surface gravity of Earth, and the Moon 1/6, so we should expect their features to be around 9 times and 36 times greater in their linear dimensions: and based on observations of collapsed lava tubes, they do indeed roughly follow that scaling (prominent tubes are roughly 20-30 meters wide on Earth, 40-400 m on Mars, and 500-900 m on the Moon, and we’d expect their height to scale by the same amount).

The trouble, of course, is that often all else is not equal. The thickness and material properties of the crust, the properties of the atmosphere, and the strength of tectonic forces varies across bodies, often in ways determined in part by surface gravity.

Let’s consider, for example, the case of a mountain range created at a convergent plate boundary on a world with Earthlike plate tectonics. There are 3 main factors acting to control the ultimate height of that mountain range:

- First, the lateral tectonic forces pushing on the crust from both sides, compressing it and causing it to bulge upwards.

- Second, the force of gravity, pulling the heavy mountains back down into the crust. This is complemented by an upwards force from the mantle called isostasy; the compression by tectonic forces also causes the crust to bulge downwards into the mantle, but the crust rock is more buoyant than the surrounding mantle, so it’s pushed back upwards (ultimately this buoyant force also comes from gravity, but is a tad more indirect). The combination of these downwards and upwards forces squeeze the crust, pushing it outwards against the tectonic forces.

- Finally, erosion on top of the mountain will wear it down, and tend to do so faster as the mountain rises further above its surroundings. But this also depends on local climate as well, and in particular glaciers tend to cause stronger erosion, implying that mountains may be able to grow higher in hotter regions before they’re stopped by glacier formation.

|

| Controls on mountain height. Wang 2020. |

Exactly how important all these factors are is a matter of some debate. Conventional knowledge for a while has held that mountain height is controlled by a balance between tectonic forces and erosion, and in particular the “glacial buzzsaw”; mountains grow until their peaks are cold enough for large glaciers to form, which then cut them down as fast as they’re being pushed upwards. This would imply that the weaker gravity and isostasy on lower-gravity worlds wouldn’t impact mountain height much—though on the other hand, lower gravity also causes taller atmospheres, meaning that temperatures drop slower with altitude. This scales linearly with gravity, meaning that—all else equal—a planet with half the surface gravity would have to grow mountains twice as tall to have the same temperature at the peaks (atmospheric composition will also have an impact, though surface pressure shouldn’t actually matter too much, except through indirect impacts on climate and precipitation). But even without glacier formation, increasingly tall mountains will have correspondingly steeper slopes, causing stronger erosion by streams and runoff—though the strength of such erosion will also vary with gravity to some extent.

However, recent work has challenged that model, instead asserting that mountain height is controlled by the balance between tectonic forces and gravity/isostasy, in which case we may indeed expect height to vary significantly with surface gravity. But let’s not jump to any conclusions: the relative importance of these factors may vary between individual cases. Weaker isostasy on lower-gravity planets may allow mountains to grow higher, but higher and steeper mountains may have ever stronger erosion until it does become a limiting factor.

And ultimately tectonic forces are also driven by gravity; Current theory holds that the main force driving tectonic plate motion is the pull of subducting slabs sinking into the mantle, and the strength of that pull scales with gravity. So a lower-gravity planet may have weaker isostasy and weaker tectonic forces, such that the two roughly cancel out. But then again, the strength of slab pull also depends on the density of the crust and upper mantle, which will vary as a planet ages and cools, and it may be that these factors must balance out to give tectonic forces roughly equal to Earth’s in order for plate tectonics to occur at all. Of course, these factors will impact the strength of isostasy as well, though they won’t impact the downward force exerted by the mountains on top of the crust. There are also various other factors like the material properties of the crust and friction between sections of rock that I haven’t mentioned but also contribute in some small part to the development of mountain ranges.

At this point, we’re reaching the edge of our understanding of tectonic forces, and asking unanswered questions about the fundamental mechanisms of plate tectonics. There seems to be enough evidence from a few different models to suggest that mountains formed by plate tectonics should be taller on worlds with lower surface gravity, just not to the extent predicted by Kaula’s rule. Beyond that, I can’t really speak with any confidence. Smaller features should also generally scale inversely with gravity, but I won’t venture a guess as to exactly how much.

In Summary

This has just been an overview of the most prominent landforms resulting directly from tectonic and volcanic activity. There are various other rarer or subtler landforms named by geologists, but this list should at least give you a sense of what the tectonic history we created earlier will actually do to your world; what different areas look like as a result of their geological history, and how this will impact life and society in the area. In the next post, we’ll look at landforms created by erosion, which are of course partially determined by underlying geology, but also strongly linked to climate.

- Major mountain ranges will tend to appear in 4 varieties, depending on their formation mechanism:

- Subduction along a shoreline will usually form an Andean-type range, with a high, thin volcanic front, but often a lower outer-arc ridge separated by a forearc basin.

- Flat-slab subduction will form a Laramide-type range, with the same features but a broader plateau.

- Collision between continents will form a Ural-type range, with a high, thin range with but with little volcanism and no outer-arc ridge—though there may be a low foreland basin.

- Complex collisions between many small landmasses may form a Himalayan-type range, with a broad, high plateau.

- Several other types of mountains may form around these main ranges:

- Fold-and-Thrust Belts will form due to compression of the crust, and form long, parallel ridges.

- Basin and Range mountains will form due to extension of the crust, and form shorter, more ragged ridges.

- In some cases, amorphous highland regions without much structure may appear as well.

- Suduction zones on the trailing edge of continents will form an offshore line of islands covered in volcanic mountains.

- Subduction in the ocean will form a line of volcanic islands on the overlaying plate, which will gradually grow over time to eventually form landmasses with Andean-type mountain ranges.

- Hotspots can form in association with mantle plumes, due to spreading of the crust, or in essentially random locations, and form single volcanoes or volcanic islands or clusters of them.

- Long-lived hotspots may form a chain of volcanoes or islands due to the movement of tectonic plates over the static hotspot.

- Non-volcanic islands may form due to rifting away of a small landmass (microcontinent), incomplete rifting of a landmass from a larger continent (“failed microcontinent”), or uplift of oceanic crust in a closing ocean (ophiolite)

- Young continental rifts form a long, shallow valley, often with low ridges on either side and scattered volcanoes.

- Transverse faults may form on plate boundaries, but can also form within plates, displacing surface terrain and forming long valleys.

- Uplift can occur outside of mountain ranges due to flat-slab subduction (associated with Laramide-type orogenies), compression of the crust, upwelling of mantle rock (associated with LIPs, continental rifts, and possibly supercontinent breakup), and retreat of large glaciers.

- Impacts by asteroids and comets form round craters regardless of impact angle, with large craters having uplifted terrain at their centers.

- Continental rifts and hotspots tend to cause effusive volcanism, forming shield volcanoes, fissure vents, lava fields, and lava tubes.

- Subduction zones tend to cause explosive volcanism, forming stratovolcanoes, lava domes, and volcanic plugs.

- Large supervolcanoes will form calderas instead of volcanic cones.

- LIPs can cover entire regions in plateaus of volcanic rock.

- Though many topographic features will tend to be larger on planets with lower gravity, it’s unclear whether this is the case for features formed by plate tectonics.

Notes

Plinian eruptions are actually one step on a scale of eruptions: In order of increasing size, they are Hawaiian, Strombolian, Vulcanian, Peléan, Plinian, Ultra-Plinian, and Supervolcanic; the boundaries are loosely defined, but each step up represents roughly an order of magnitude increase in volume of material erupted and decrease in frequency of eruptions. Most of the most famous and catastrophic eruptions of human history have been Plinian, but there have been some fairly devestating Peléan and even Vulcanian eruptions as well.

In case you were wondering, Io’s volcanoes fall into varieties roughly analogous to Earth’s, despite the difference in tectonic regime: Some volcanoes are predominantly effusive, others more explosive, and there are depressions filled with volcanic rock called “pateras” that appear analogous to supervolcano calderas on Earth, though more common.

I didn’t include the addition of material on top of a mountain range by volcanism as a factor in maximum mountain height, because that extra material still has to be supported by tectonic forces, and generally material isn’t being added fast enough to overcome removal by erosion. The highest mountains on Earth don’t even have significant ongoing volcanism.

It’s kind of a running joke in the geological community (the

less mature of us, anyway) that a lot of our terminology lends itself to double

entendres, and I have to admit that the coining of the term “megathrust shear force” certainly doesn’t buck that trend.

Yes, this post is in a new font (Montserrat). I think it reads a bit better, and bold words stand out more. I'll switch old posts to it as I update them.

The “Subscribe by email” widget I had on the sidebar for a little while was based on a service that announced that it was shutting down email subscriptions shortly after I added it. I’ll look for a more robust email subscription service in the future.

Buy me a cup of tea (on Patreon)

Part VIIb

Very comprehensive, as always. Next you need to explain the arachnoids on Venus...

ReplyDeleteYou know, I hadn't been planning on it, but now I think about it maybe at some point I'll do a supplement just for landforms that don't appear on Earth

DeleteThank you for this, it was very enlightening!

ReplyDeleteAny idea when you'll add the article about erosive forcings and the subsequent practical case? I'm nearing the end of the climate forcings on my map and looking forward to define my planet's geology.

I've been working on it, but I've got a bit sidetracked learning how to run a lightweight climate model, and I'll have a tutorial for that out next (hopefully soon, but I have been saying that to myself for a while now...)

DeleteI’ve been using these while studying geology in university, and are quite helpful for that. Thank you