For a while now, I've been using the Köppen-Geiger climate classification system for my climate tutorials and

explorations, for much the same reason it's commonly used for studies of

Earth's climate; it's a flexible and widely-recognized standard that sums up

the most important climate distinctions without getting too lost in fine

details (for the most part).

Still, some of the climate states we've been exploring are clearly

stretching the limits of what the Koppen system can sensibly describe, with

extremes of high temperatures or seasonal variability far beyond what we see

on Earth. I've had a fair few people ask if I would consider adding new

categories to the Koppen system, or propose full alternative systems of of

their own, and so far I've generally declined for two reasons:

-

I want these results to be directly comparable to Koppen maps already

made for Earth, and not require casual readers to get acquainted with the

specifics of any new system I invent.

-

The Koppen system is tuned based on observations of how climate affects

vegetation cover on Earth; any modification would presumably be intended

to better reflect vegetation cover on other planets, but because we can't

actually observe vegetation on any such planets we have no way to tune

those modifications.

When I started this post, I thought this would stay my position, but the

more I looked into the matter, the more I began to think there are actually

some reasonable improvements that could be made. And, unsurprisingly, that

line of investigation ballooned a bit in scope, so I'll be tackling the

question of alternatives to the Koppen system in three parts: first, we'll

explore modifications to the Koppen system or whole alternative climate

classification systems proposed by climate researchers throughout the

history of the fireld, seeing what lessons we can take in terms of how these

systems apply different climate parameters or choose to make different sorts

of distinctions; second, I'll attempt to construct my own bioclimate

classification system based on these lessons; and third, I'll see how some

of the exotic climate states we've explored previously are represented by

this new system.

(Quick terminology note: properly it's the Köppen or Köppen-Geiger classification system, but I'll just be saying Koppen because

it's shorter and pasting in the umlaut without Blogger's text editor messing

up the font is a pain).

Biomes and Climate Classification

First off, let's clarify our goals: for the most part what we really want

to know is what biomes a planet will have, meaning what types of

life—vegetation in particular—are dominant within different areas. There have been numerous schemes to

classify Earth's biomes, with

this being a typical breakdown

(that site also includes a more detailed breakdown into ecoregions, which

are more geographically constrained such that they contain not just similar

types of life, but similar specific species); but see also

this approach, which is a bit

more detailed in some cases but doesn't attempt to divide areas into

exclusive zones. You may have also seen this popular map before, which so

far as I can tell was made by one Wikipedia user as a synthesis of various

sources (and they did a fair enough job of it, to be clear):

The trouble of course is that these systems are designed to

describe the biomes observed on Earth rather than predict the

biomes we might see elsewhere (they're also often a bit specifically tuned

to the particular varieties of life present on modern Earth, so won't apply

well to alien worlds or even past Earth before the Cenozoic).

Climate classification systems are based on the assumption that biome

distribution is (for the most part) controlled by climate, and so we should

be able to predict the most likely biome in a location based just on some

key parameters of its climate; even on an alien planet with life unrelated

to that on Earth, we can expect (however tentatively) that similar

environmental influences will create similar ecological niches. All the

systems we'll discuss today consider two main types of climate factors influencing growing conditions

for plants in any area: thermal factors and

water factors.

Thermal factors generally means temperature, but this impacts

plant growth in two primary ways: first, tolerances: Certain plants

can only tolerate certain ranges of temperature before suffering damage. 0 °C is the most important tolerance threshold, as sub-freezing

temperatures cause frosts that can damage exposed soft leaves, stems, and

shallow roots, though some plants may be able to tolerate brief nighttime

frosts but not sustained subfreezing temperatures. To a lesser extent,

some tropical plants may not tolerate temperatures below around 10 °C well, and some mildly frost-tolerant trees may be damaged at

temperatures well below freezing.

Second, temperature informs the growing season: Broadly speaking,

plants grow best between about 20 and 30 °C, with very little growth below 10 °C and essentially none below 0 °C. In seasonal climates with winter frosts, leaves and soft stems may have

to be lost in winter, or a smaller plant may attempt to complete its

entire life cycle in one year and rely on its seeds surviving winter; the

longer and warmer the growing season between winters, the more plants can

invest in larger leaves and other soft structures, with the expectation

that they can recoup the cost of growth before they have to lose those

structures to conserve nutrients in winter; a very short and cool growing

season inversely encourages more gradual growth between years and more

structures that can tolerate the cold without being lost. Hence the

general spectrum of Earth from broad-leaved evergreen trees that

can keep their leaves all year without fear of frost, to

deciduous trees that grow large leaves but then lose them in

winter, and coniferous evergreen trees that retain small

needle-like leaves through freezing winters (with a parallel gradient in

short-lived undergrowth towards smaller varieties that require shorter

growing periods and can better tolerate early frosts).

The water factor represents availability of water in the soil, also

necessary for growth, but with the complication that water level in the soil

depends not only on input of water from precipitation (rain and snow)

but also loss of water to evapotranspiration (combined surface

evaporation and transpiration through the plants' own leaves).

Evapotranspiration generally increases with temperature, so warmer areas

generally require more precipitation to ensure sufficient water

availability, but timing of precipitation also matters: in a climate with

substantial temperature variation, more precipitation will be needed in

summer than in winter to balance evapotranspiration, and if all

precipitation arrives in one short burst, it may all evaporate and leave the

ground dry for the rest of the year. Precipitation

generally correlates with temperature, offsetting the importance of

evapotranspiration variation a bit, but not always, so you'll see that some

classification systems essentially try to track a precipitation seasonal

cycle separate from the thermal seasons.

Though these mechanical considerations are taken into account to varying

extents by different systems, ultimately they're all still based on

observational data; climate data is compared to biome distribution and the

researchers try to work out what ranges of the former best match up to the

latter. They can be extrapolated to other contexts, much as a we can look at

observations of star mass and luminosity and create formulas to predict

luminosity for fictional stars based on mass. But, much as with those

formulas, this approach is only really reliable within an intended range of

use. Most of these climate classification systems are intended for use on

Earth and so make various assumptions about what range of climates you can

expect to encounter, what exact type of climate data you might have

available, and what parameters can be assumed to correlate or ignored

entirely.

In particular, a lot of these systems, especially the older ones, assume

that direct observations of factors like minimum temperature or

evapotranspiration are not available, and so rely on proxies: other

parameters that are assumed to correlate to these factors well enough to be

taken as direct indicators of them. The assumed correlations are, again,

tuned based on observational data on Earth, so may not apply well to other

planets. One common issue we'll see is that average annual temperatures are

used as a proxy for overall temperature range based on some assumed seasonal

pattern, or monthly temperature averages are used as proxies for maximum and

minimum temperatures based on assumed daily variation, but these assumptions

won't hold particularly well for planets with very different seasons or

days.

But even that issue aside, biomes are not actually solely determined by

climate; soil quality, topography, fire frequency, and herbivory by animals

all influence vegetation distribution as well (though many of these factors

do correlate to climate to some extent, but often not perfectly). Thus no

climate classification system will perfectly match biome distribution (and

many biomes are divided by gradual gradients rather than hard boundaries

anyway), which has led to something of a division in the philosophy of how

climate classification systems are developed and what each climate zone is

meant to represent:

-

What we might call boundary systems still attempt to correlate

climate directly to biomes, with each zone taken to correspond directly

to a specific biome and predict its distribution, such that the

boundaries seen on the climate map represent real boundaries between

biomes in reality—even if we have to accept a certain margin of error and "fuzziness" to

these boundaries in practice.

-

Alternatively, what I'll call gradient systems abandon any such

direct correspondence and instead use zones as indicators of the overall

gradient in major thermal and water factors; there's still some

correlation to biomes in that, for example, areas indicated as wetter

might be expected to be lusher, but an individual zone doesn't

correspond to a single biome, and the boundaries between zones aren't

assigned any particular importance either; instead, zone boundaries are

used to show the progression from drier to wetter or colder to warmer

areas with a bit more visual clarity than something like a color

gradient might provide, much as a topographic map might use contour

lines to show elevation.

Much has been said over the years of the relative advantages of each;

boundary systems may sometimes be misleading where their boundaries don't

match well to actual biomes, but gradient systems may be less intuitive to

read and fail to give us a clear picture of what to expect specific areas to

actually look like.

Beyond that, it's perhaps best to compare these approaches by seeing them

in practice; so with all that in mind, let's go through a few of these

systems and see how they approach these challenges and what limitations that

imposes:

Köppen-Geiger Climate Zones

The Koppen system was developed over a series of papers from 1884 to 1961,

the final couple papers published after Koppen's death based on his notes by

his colleague Geiger, hence the double-barreled name. It determines all

climate zones based on monthly averages of temperature (typically

taken to be near-surface air temperature at about 2 meters height) and

precipitation, using combinations of these factors to define 5 main

climate groups split into 31 individual zones—though various simplified schemes with ~14 main subgroups are fairly

common. It is, of course, a boundary system, and easily the most famous of

the type, though it's not hard to find areas on Earth where the boundaries

don't align terribly well with actual observed biomes. This has given it

something of an ambiguous double-identity over time, where even though it

was constructed based on observed correlations between climate and biomes,

it is not always presented or used solely as a system for predicting biomes,

but sometimes as a system for classifying general climate conditions that is

conveniently related to biomes but not necessarily bound to replicate

them.

|

A fairly familiar map, though I think this uses the 18

°C average threshold

for thermal arid zones.

Wikimedia

|

But if we are primarily concerned with its performance in predicting

biomes, there is a logic to how it classifies climates, though not always a

wholly intentional one; the system was originally constructed with a largely

empirical approach, where zone definitions were chosen based on how well

they correlated to biomes, even if the reasons for that correlation weren't

clearly known at the time (there was also some ambiguity in how some zones

were defined in Koppen's original papers, but a consensus on standard

interpretations has emerged over time). But with the benefit of modern

knowledge, we can see clear functional relationships in retrospect:

First, the distinction between arid (B) and non-arid zones is determined by

essentially using temperature as an evapotranspiration proxy, calculating an

aridity threshold that represents a total precipitation level low enough

relative to evapotranspiration for the region to be dry most of the year,

with adjustments for distribution of precipitation throughout the year to

account for greater evapotranspiration in summer. Arid zones are then

subdivided into steppe (BS) zones, which might still get enough water for

widespread vegetation of some kind, and true deserts (BW), too dry for much

growth.

The remaining groups and many of the subdivisions are defined by thermal

limits, using monthly temperatures as proxies both for tolerances and the

overall shape of the growing season, in particular relative to the 10 °C threshold below which most growth is assumed to stop:

-

Tropical (A) zones have all months above 18 °C, warm enough both to ensure that even brief nighttime frosts are

unlikely and that good growth is sustained year-round.

-

Temperate (C) zones have their coldest month between 0 and 18 °C, such that winters are cold enough for growth to slow and for winter

frosts to be possible, but sustained freezing temperatures are

unlikely.

-

Continental (D) zones have at least one month below 0 °C, such that there will be sustained frosts and potentially

temperatures low enough to damage some moderately frost-tolerant

plants.

-

Polar (E) zones have all months below 10 °C, such that there is essentially no growing season.

Then, within C and D zones:

-

Hot-summer (Xxa) zones have at least one month above 22 °C and 4 above 10 °C, indicating a long, warm growing season.

-

Warm-summer (Xxb) zones have cooler summer peaks but still at least 4

months above 10 °C, so a more moderate but still reasonably long growing season.

-

Cold-summer (Xxc) zones have no more than 3 months above 10 °C, so only a brief growing season which may thus not sustain deciduous

plants and tall grasses.

-

D zones then also have extremely cold (Dxd) zones, with no more than 3

months above 10 °C and 1 below -38 °C, cold enough to damage even some hardy trees, such that even

conifers must drop their needles in winter.

Arid B zones are generally assumed to have too little water for sustained

growth anyway, so growing season concerns are ignored, but a 0 °C threshold for the coldest month is still used to divide hot (BXh) and

cold (BXk) varieties to reflect different frost tolerances. Some sources

still use an 18 °C threshold of annual average temperature for this division, which is

perhaps intended to include some indication of growing season intensity as

well, or the point where desert plants with C4

photosynthesis, which is advantageous in hot, dry conditions, dominate over

those with more common C3 photosynthesis.

E zones are also subdivided into tundra (ET) zones, with at least one month

above 0 °C, allowing for some slow growth, and ice cap (EF) zones, below

0 °C in all months and thus having effectively no growth and likely becoming

covered in ice.

Orthogonal to these thermal divisions are a set of divisions based on

seasonal precipitation patterns, essentially reflecting the degree to which

water is available during the growing season:

-

Monsoon (Xw) zones have wet summers, ensuring plentiful moisture levels

during the growing season, even to the point of being hazardous, encouraging adaptations to tolerate flooding or avoid collecting

water on leaves.

-

Mediterranean (Xs) zones have wet winters but dry summers, such that

there's little rain during the growing season but plants may still have

sources of groundwater, flowing water, or internally stored water to

rely on, allowing for more substantial growth than arid zones but still

causing patchier vegetation cover and encouraging adaptations to

conserve water.

-

Humid (Xf) zones have some but not excessive rainwater available during

growth.

The exact definitions vary (as do naming conventions), but though Xw and Xs

zones are often defined in seemingly symmetric ways (usually comparing the

wettest month in one thermal season to the driest in the other), they're

really reflecting different phenomena and so have different thresholds, and

Mediterranean adds an extra requirement that summers also be dry in absolute

terms (otherwise it doesn't matter that winters are wetter, because

vegetation can still rely on immediate sources of water from precipitation

through summer rather than having to conserve water from winter).

Tropical zones essentially lack substantial thermal seasons (on Earth

anyway), so the relative timing of rains isn't too important—it's always warm enough to grow—and they can be divided into a simpler system based on the regularity of

the rains:

-

Rainforest (Af) with year-round rains.

-

Monsoon (Am) with some dry periods that must be tolerated but still

enough overall rain to allow for substantial forests.

-

Savanna (As/Aw) with too little rain for dense tropical forests, but

still more vegetation than seen in arid climates. This can be subdivided

into dry-summer (As) and dry-winter (Aw) varieties, but again the

distinction is usually unimportant when all months are warm enough for

growth.

All in all, this scheme pretty well suits our purposes for a number of

reasons:

-

Monthly average data for precipitation and temperature aren't too hard

to produce; basically any GCM like ExoPlaSim or ROCKE-3D should be able

to do it, and even if you can only do the hottest and coldest month of

the year this is usually good enough to estimate zones if you're willing

to make a lot of assumptions about how representative these months are

of the whole seasonal cycle.

-

The system specifically checks seasonal extremes of temperature and

precipitation rather than assuming their variation based on annual

averages or other proxies, so it's somewhat flexible in allowing for

different ranges and "shapes" of seasons.

-

The number and specificity of zones is fairly well tuned to show us a

lot of detail without digging too deep into distinctions only important

for the particular species of modern Earth.

Still, the system was simply not designed with application to other planets

in mind, which leaves us with a number of quandaries in its application,

several of which I've mentioned before:

-

The use of monthly averages makes it a bit ambiguous how different year

lengths should be approached; if a planet has years half as long as

Earth, should we split that year into 6 months to preserve month length

or 12 months to preserve number of months per year? When testing for

tolerances, my inclination would be to maintain month length, presuming that the relationship between monthly average and the

actual extreme conditions depends to some extent on month length, or

that brief excursions to extreme conditions may be tolerable—but when testing for type of growing season, I'm unsure if it would be

more sensible to assume plants will adapt around different year lengths

(a shorter year may mean less time to grow but also a shorter winter to

survive) or if the absolute length of each growing season is always the

most important. There's also presumably some minimum year length below

which we should consider there to effectively be no seasons, but again it's hard to say where exactly that should be.

-

The system makes no distinctions in temperature above 22 °C and marks

all areas with a coldest month above 18 °C as tropical or arid. On Earth this is fine as few non-arid regions

have months much over 30 °C, but we've seen a few cases in our

explorations of climates with summers reaching to 60 °C or more, which

is high enough to be a serious hazard for Earthlike life, while still

having more hospitable periods of year.

-

Similarly, defining the aridity threshold using temperature as an

indirect proxy for evaporation works well enough within the intended

range of temperature, but the formula used may not be tuned as well for

very hot planets outside the original intended range of the Koppen

system—and flat precipitation thresholds for Mediterranean and tropical zones

may similarly not extend well to some extremes.

-

Though the system is fairly flexible in terms of the exact shape and

range of seasonal variation, it still assumes a single seasonal cycle

per year: one warm summer and one cold winter, as well as one wet period

which will mostly align with one or the other of these thermal seasons.

Planets with very high obliquity seem to show much more complicated

seasonal patterns, with some areas having two warm periods and two cold

periods per year, and others having two wet periods between a dry summer

and winter. To a lesser extent, the system also tends to assume

seasonality for all temperate regions, which may not always be

true.

There's also various quibbles to be had about how well the system

represents specific biomes or regions. These can often be somewhat

subjective, but there's two I'd choose to highlight:

-

Though the driest areas are marked as arid, there's still a range of

somewhat wetter semiarid climates not well represented here, which

makes the interpretation of some zones fairly ambiguous; D zones in

particular tend to cover a broad range from dense forests to open

grassland, and Aw/As also covers a fairly diverse set of variously dry

to wet or open to densely forested biomes (none of which correlate

well to the As/Aw distinction).

-

At the same time, in other areas the D zones are somewhat excessively

subdivided based on the overlap of seasonal precipitation and thermal

classes, creating a number of rare subtypes that don't correlate to

any particular biome distinctions.

At any rate, this hopefully gives us a bit more of a baseline to assess

our potential alternatives. To help with that task, I've been working on a

substantial rewrite of my koppenpasta script to make it easier to

implement different classification systems and incorporate different data

outputs. Though the updated script is not quite ready for public release,

I can use it with some

climate data of modern Earth

to produce some maps of these different climate classification systems for

easier comparison—note that this is averaged data for only land areas from 1981 to

2010,

and that the dataset included only average daily high and low temperatures

for each month, but the average of the two seems to be a good

approximation for monthly average temperature. Here is the standard

Koppen-Geiger zones to start with, including As and using the

0 °C

coldest-month threshold for dividing hot and cold arid zones:

|

I've added a function to the script to auto-generate map keys, which

I'll be using for these maps, but it only includes zones which

actually appear on the map, hence the lack of Dsd here; though it

does manage to pick up a couple patches of Csc in the Rockies.

|

As the most popular climate classification system in use for near a

century now, the system has accrued a lot of what we might call "Koppen

apocrypha" over the the years, alternate interpretations of the somewhat

inconsistent original texts or attempts to tweak the system to better

address some of its shortfalls either globally or specifically tuned to

the conditions of a particular region. The original papers themselves

sometimes suggested a somewhat more complex system of water availability

classifiers, including options for an autumn wet season or two distinct

wet seasons, and a "fog" zone for deserts where frequent fog provides some

moisture despite the lack of rain, but failed to provide strict standard

for these and so they've rarely been used in practice. There are, however,

a few more comprehensive attempts to overhaul the system that are worth

noting here.

Köppen-Trewartha Climate Zones

This is a modification of the Koppen system, first published in 1966 but

with various later refinements. It mostly focuses on increasing its detail

in temperate and continental areas; the details vary by source (I'm mostly

going by

this one),

but typically the main difference is the rearrangement of Koppen's C and D

groups into 3 groups:

-

Subtropical (C), with at least 8 months above 10 °C.

-

Temperate (D), with 4-7 months above 10 °C.

-

Boreal (E), with no more than 3 months above 10 °C.

-

(Polar then gets bumped over to F.)

So essentially it's a scheme to get an even more detailed breakdown of

growing season length to better reflect some biome distinctions

within the mild climates, with the Xxb/Xxc distinction in Koppen also

promoted to a group boundary along the way.

|

|

Comparison of the main subdivisions of the Koppen (top) and

Trewartha (bottom) systems applied to Earth (note that the former

uses the old -3 °C threshold for dividing C and D zones).

Belda et al. 2014

|

Temperate zones are then subdivided into oceanic (Do) and continental (Dc)

based on whether the coldest month drops below 0 °C, corresponding to Koppen's C/D division. The same distinction could also

be applied to C and E zones, but on Earth at least Cc and Eo zones are

fairly rare, though the latter is still sometimes included when coastal or

highland patches of it are relevant. C and D can also be be divided into Xxa

and Xxb zones with the same 22 °C threshold for the hottest month as in Koppen, though

some authors

go further and classify all zones based on their warmest and hottest

months—10 levels of each, for 55 possible combinations (however many total zones

that works out to after accounting for the reasonable temperature ranges

that can be applied to each major type, I leave as an exercise for the

reader).

Sometimes an additional highland (G or H) group is included, indicating

areas where the main thermal grouping is different to what it would be at

sea level, assuming a lapse rate of 5.6 °C, but a lot of recent applications exclude this; broadly speaking, plants

don't care much what altitude they're at independent of the effect it has on

thermal and water factors or soil quality.

The Xw/Xs/Xf zones are also applied from the Koppen scheme, but comparing

rainfall over the entirety of the warm and cold halves of the year rather

than just the extremes of each, and usually only applied to C zones, largely

just because Earth's circulation patterns make heavily seasonal rain

patterns rarer towards high latitude but also because the cold temperatures

and thus low evaporation makes seasonal water availability less of an issue

generally. This does, notably, make both Cs and Cw zones fairly rare, with

the former excluding large areas usually considered Mediterranean biomes.

Trewartha also often includes a different aridity threshold for B zones

(using a more continuous adjustment of the aridity threshold to seasonal

precipitation rather than sharp categories) and sometimes excludes the Am

zone, but really this is all just down to divergent evolution; these

modifications could easily be applied back into Koppen, or some of the

recent modifications of Koppen brought into Trewartha.

For my part, I've implemented Trewartha in koppenpasta with a simple

14-zone scheme, mostly following my main source above but I've added the

Eo/Ec distinction and tweaked some of the colors for better legibility. I'll

also add various options to apply elements of the Trewartha algorithm to

Koppen or vice-versa.

Ultimately, if we don't bother with the numerous thermal subtypes then the

overall picture it's showing us isn't all that different from what we get

using Koppen, with the C/D line being the only genuinely new piece of

information, but the greater emphasis on growing season length might be

useful for some purposes, and trimming of the various continental subtypes

makes for a cleaner result. Some of the minor improvements might be worth

bringing into Koppen, though the difference they make is probably less than

the inherent error in ExoPlaSim (and it looks like this might exacerbate

ExoPlaSim's bias towards aridity in the tropics).

FAO Global Ecological Zones

This is

a system

developed by the UN Food and Agricultural Organization around 2010 to

classify global forests which is mostly derived from Trewartha but with some

oddities. The given definitions are a bit ambiguous in some places and the

distinction between boreal forest and tundra is defined by direct

observation of vegetation rather than climate data, so overall it doesn't

quite constitute a functional climate classification system I could easily

apply elsewhere.

But I thought it worth noting for its approach to aridity; rather than a

single annual threshold for aridity, months are individually defined as dry

if precipitation in cm is less than twice the

temperature in °C—a common rule of thumb for dry conditions that roughly aligns with Koppen's

aridity threshold if averaged over a year. Areas that are dry all year are

defined as deserts (with a separate desert zone for the tropical,

subtropical, and temperate groups rather than a separate arid group); areas

with some wet months but where total annual evaporation still exceeds

total precipitation (exactly how evaporation is determined isn't specified)

are semiarid steppe; other tropical areas are divided based on the number of

wet and dry months, similar to the division of colder areas based on growing

season; and Mediterranean (or "subtropical dry forest") zones are defined by

having a wet winter and dry summer, though exactly how that's determined is

particularly ambiguous.

Paleoclimate Modified Köppen

This comes from a study

investigating how well prehistoric Koppen climate zones can be reconstructed

based on geological data. This data is usually insufficient to reconstruct

the details of seasonal temperature and precipitation variation, as would be

necessary to properly apply Koppen zones.

As we've seen, climate models can be tuned to match geological data to attempt to

reconstruct this data, but aren't fully reliable. This study attempts to create new definitions that best match the existing

Koppen zones based only on the data that can be most reliably estimated for

the past: average annual temperature,

average annual precipitation, and

temperature of the warmest month.

|

|

Modified Koppen definitions applied to modern climate data (top)

compared to classical Koppen definitions (bottom); see the paper for

zone definitions.

Zhang et al. 2016

|

The result isn't a particularly close match, and they have to abandon the

Xw/Xs/Xf categories for lack of good data on seasonal precipitation

patterns, but it's an interesting attempt to rebuild these patterns from

such limited data. It's not particularly relevant to our case, though; it

relies heavily on assumptions about how annual averages relate to seasonal

variation, and though publicly available climate model data is sometimes

quite limited, I've yet to see a dataset that included temperature on the

warmest month but not the coldest and with no associated monthly

precipitation data.

Algorithmic Köppen-like Climate Zones

I include this more as a curiosity than a real consideration:

One 2012 paper

uses a computer algorithm to attempt to regroup the world's land area into 5

top-level groups, 13 second-level subgroups, and 30 third-level zones based

on temperature and precipitation data, mirroring the breakdown of the Koppen

system, but optimized to minimize variation of temperature and precipitation

conditions between areas within each zone.

|

|

The algorithmically produced classification system; see the paper for

definitions.

Cannon 2012

|

It's a bit interesting to see the way the algorithm placed more focus on

tropical and arid regions at the expense of the temperate regions, but

ultimately climate classification systems are, again, an attempt to predict

biome distribution based on climate, and this study didn't use any

vegetation data either as input to its algorithm or for assessing the

results, so I feel like it's largely missing the point (though to be fair to

the author, they seemed more interested in the potential for such a system

to better describe the effects of climate change).

A number of other papers have also used similar approaches for classifying

climate, most often using

k-means clustering, which attempts to divide areas into clusters where each point in the

cluster has parameters closer to the average for that cluster than that of

any neighboring cluster, but with the same issue that the results tend not

to correlate too well to actual biomes and won't apply well to other

worlds.

Thornthwaite

Moving on from the direct Koppen derivatives, we'll start with a system

that's fairly obscure today but worth starting with because it was

conceived from the outset as something of the gradient system antithesis

to Koppen's boundary system thesis, developed concurrently in the 30s and

40s in direct response to Koppen's growing popularity.

The main innovation over Koppen is an attempt to better represent the

water balance of a region by eschewing any proxies for evapotranspiration

and instead attempting to directly measure

potential evapotranspiration (PET), the total evapotranspiration that would occur if unlimited groundwater was

available. This was originally determined based on monthly averages of

temperature and daylight hours, but modern methods based on

the

Penman equation

are generally more reliable and easier to apply to other planets. PET can

then be compared directly to precipitation to determine an overall water

balance in each month; where a region has higher precipitaiton than PET,

there's a surplus of water which will run off into rivers and the sea;

where precipitation is lower, there's a deficit of water which will reduce

soil moisture.

Without getting too caught up in the thorny (har har)

math, monthly measures of surplus or or deficit are used as the system's

water factor, while PET on its own is used as the thermal factor (because

higher temperatures cause a greater PET). Specific climate zones can then

be classified into two main types based on annual averages of these

factors, with subtypes based on their seasonal variation:

-

Moisture Index, based on the balance of total annual surplus

and deficit.

-

Seasonal Variation of Effective Moisture, based on the total

deficit of water in the dry season for wet climates and surplus in

the wet season for dry climates—thus giving some sense of how much the climate seasonally diverges

from its average conditions implied by the moisture index—as well as which of summer or winter are drier (the seasons

presumably determined by temperature or PET).

-

Thermal Efficiency, defined by total annual PET.

-

Summer Concentration of Thermal Efficiency, defined by the

portion of annual PET in the 3 hottest months.

Though some of the earliest versions of the system seem to indicate some

ambition to correlate these climate types to biomes, ultimately this was

abandoned over further refinement in favor of a regular division of the

parameter range into zones (e.g. each boundary between thermal efficiency

types represents an increase in total annual PET by 142.5 mm), on the

argument that this represented a more "rational" approach to classifying

climate rather than potentially subjective attempts to link climates to

biomes.

Considering all the potential types and subtypes, this works out to over

3,000 possible combinations, though not all of them may be terribly

likely, and with a bit of grouping together of the more similar types we

can perhaps pare that number down to 360. The main idea here is really not

so much to divide up the planet into a recognizable few climate zones, but

more to have shorthand designations for climates describing their main

features. But because of that inability to produce an intuitive map and

the somewhat arcane algorithms for determining individual zones (a major

drawback before easy access to computers), it simply never gained much

popularity. Even within more niche communities of climate research, such

specificity never proved particularly useful; broad categories like

"mediterranean" or "rainforest" can be useful for stating generalities,

but to describe the particular climate of a specific region, it's just

easier to directly state ranges of temperature and precipitation rather

than having to learn and remember a complex shorthand, and in the internet

age we can use intuitive visual charts like this to sum up the patterns of seasonal variation:

|

Note the clear wet-winter, dry-summer pattern of a Mediterranean

climate.

Wikimedia.

|

The Thornthwaite-Feddema variant developed in 2005

addresses some of these issues by dropping the many subtypes and

simplifying the algorithm, resulting in 36 main types that can be more

easily mapped, each a simple combination of a specific range of moisture

index and PET. This can optionally be combined with 12 types of seasonal

climate variability, indicating both the degree of variability and whether

it is primarily caused by thermal or moisture variation.

This does balloon the count of potential individual types to 432, but

again the emphasis is on the overlap of different forms of climate

variation rather than the importance of individual combinations of

factors. A clear way to represent these differences on one map is still an

unresolved issue, however; I'm not a big fan of the hatching system

attempted in the map above. For my implementation I've just chosen to make

the main types and variability types separate output options.

|

I'm not sure why I got so much more Torrid area than Feddema's map,

probably different measures of PET

|

In terms of lessons to take from Thornthwaite, I appreciate the motivation

to improve on Koppen's lackluster handling of water balance, but I think

this may be an overcorrection; depending on how you interpret the

implementation, it either ignores the influence of temperature outside of

its impact on water balance or effectively uses PET as a proxy in reverse

for temperature, neither of which are ideal. I'm also not quite ready to

give up on boundary systems just yet, though there is still more to learn

about implementations of gradient systems.

Holdridge Life Zones

This was developed around the same time as Thornthwaite, first published in

1947, and though it's not clear how much influence there was between them or

from Koppen, ultimately Holdridge represents a somewhat more successful

implementation of some of the same concepts, in terms of gaining widespread

recognition and use. So in practice, it is the most popular alternative to

Koppen. Definitions vary a bit, but I'll mostly be going by

this paper. The system uses three parameters, all averaged across the year:

-

Biotemperature, which is based on average temperature but with all

temperatures below 0 °C counted as 0 °C, and all above 30 °C counted as 30 °C, the idea being that photosynthesis largely stops outside this range

so further variation beyond it matters little to life (some sources count

temperature above 30 °C as 0 °C, but this will have odd results if we consider warmer worlds with

regions spending long periods above 30 °C). This was originally sampled based on monthly average temperatures,

but some newer studies have used daily averages.

-

Total precipitation, summed across the year.

-

Potential evapotranspiration ratio (PETR): potential

evapotranspiration divided by total precipitation; so a PETR under 1

indicates an overall water surplus, and a value over 1 a deficit.

Originally PET was estimated as biotemperature * 58.93, making this parameter directly determined by the

other two, but again better methods of estimating PET have been developed

since.

The main peculiarity (and source of headaches) of the Holdridge system is

that it then tries to squash these 3 dimensions of variation into 2, by

placing the 3 axes at somewhat odd angles. Each axis is divided into ranges

on a log-2 scale (each division is at twice the value of the last) and each

overlap of ranges of the 3 parameters roughly defines a life zone. Exactly

how to handle cases where different parameters might not line up neatly into

these categories is often left a bit ambiguous, but the

clearest procedure

I've seen is to essentially plot the position first on the

PETR/precipitation grid and then project from that point directly up or down

to the appropriate level on the biotemperature axis.

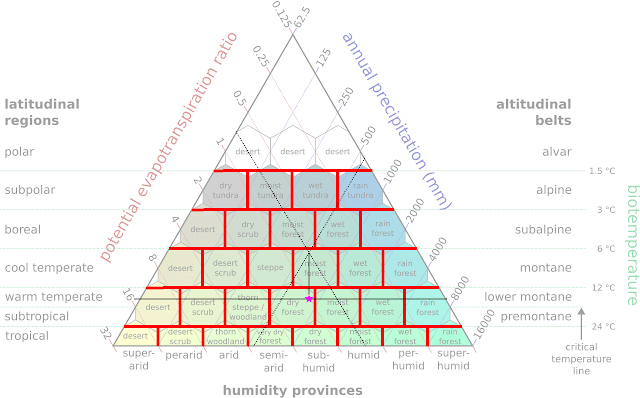

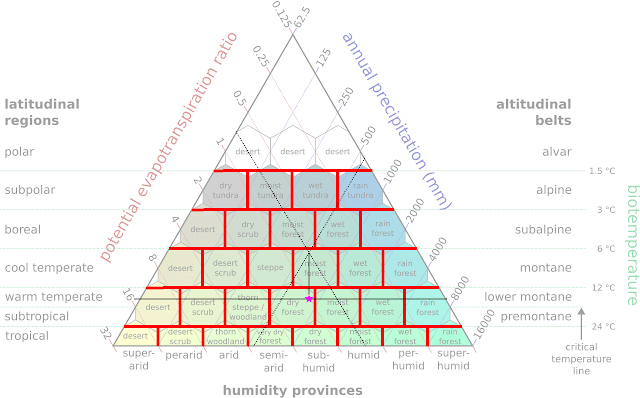

|

A typical chart of Holdridge life zones; not that they're classified

based on the angled PETR and precipitation lines and the horizontal

biotemperature lines, the "humidity provinces" indicated on the bottom

don't correspond to any particular axis.

Peter Halasz, Wikimedia

|

If we lump the polar desert zones together into one, this works out to 31

life zones in 6 latitudinal belts. However, the 12-24 °C belt is sometimes subdivided into warm temperate and subtropical belts

along the frost line, where minimum temperature drops below

0 °C at least once most years, adding 7 life zones, and much like Trewartha,

altitudinal zones due to drop of temperature with elevation are sometimes

distinguished from latitudinal zones.

The result is something of a compromise between boundary and gradient

systems; the choice of parameters, naming of individual zones, and use of

the frost line for the temperate/subtropical boundary clearly reflect a hope

that certain zone boundaries would correspond to specific biomes, but in

practice many of the intermediate boundaries don't indicate any actual

transition and just serve to show the overall gradient.

So far I've usually tended to just choose two axes—biotemperature and either precipitation or PETR depending on whether the

latter is conveniently available—and

plot life zones based on that, which is often a reasonable approximation

given the ways PETR correlates to biotemperature and precipitation.

But for the koppenpasta update I decided to finally implement a 3-parameter

approach based on the method I mentioned above: the vertical position of a

region in the Holdridge chart is determined based on biotemperature, and

then the horizontal position is determined based on the intersection on the

oblique PETR and precipitation axes. But rather than trying to work out how

this fits in the hexagonal grid usually used for Holdridge zones, I've

settled for a more straightforward staggered rectangular grid.

|

Red lines showing the staggered grid used in koppenpasta over the

standard hex-grid Holdridge chart, with black lines showing an

example of how zones are determined based on biotemperature and the

intersection of precipitation and PETR (with the star showing the

resulting point, to be classified as warm temperate dry forest).

|

I also haven't implemented a warm temperate/subtropical distinction yet, as

the Earth dataset I'm using doesn't include a convenient measure of the

frost line, but there's a few conceivable ways that could be determined for

ExoPlaSim data.

For our purposes, the main strength and weakness of the system

is that, if we exclude the temperate/subtropical distinction, then only

annual averages are required to mark zones. On the one hand this heavily

relies on assumptions about how these average relate to overall patterns

that won't work well for less Earth-like planets and can't distinguish

different types of seasonal patterns like Mediterranean and monsoon seasons,

but on the other hand it makes this system a convenient option where only

annual data is available.

Whittaker Biomes

Not so much a complete classification model as a chart, so far as I can

tell

first published around 1970. That version was a bit of a rough sketch, but derivatives or charts

like it are used fairly often in textbooks and the like to communicate the

most basic concepts of climate classification, in particular that:

-

Biomes are determined primarily by the overlap of thermal and water

factors of climate.

-

Precipitation requirements to sustain a given biome tend to rise with

temperature (due to increased evapotranspiration).

-

Biome variety tends to increase with higher temperatures, partially

because the range of precipitation values also typically increases

(more evapotranspiration in hotter climates tends to

generally increase precipitation).

There are many versions of this sort of chart, but most tend to be a bit

abstract; the Whittaker biome chart is notable for specifying particular

bounds of annual average temperature and

total annual precipitation for specific biomes, implying the

ability to classify and predict biomes based on these parameters. In

practice this is somewhat tricky because I've yet to find a mathematical

description of these boundary lines, so classification generally consists

of placing data points on a chart and trying to match this to a reference

image of the Whittaker biomes chart (and this also makes it unclear to

what extent different renderings of the chart are consistent with each

other).

I managed a rough implementation by taking a version of the chart

from here, overlaying an excel chart of temperature and precipitation with axes

scaled to match, placing data points as markers along each of the boundary

lines, and then fitting a polynomial trendline to those points, which can

then be used (along with some reasonably linear extrapolations outside the

range of the chart) to classify specific points on Earth.

|

My rough fits overlaid on the reference chart.

|

The result is somewhat underhelming, generally seeming to underestimate the spread of tropical rainforest

and overestimate that of woodland/shrubland. Temperate rainforest also

ends up occupying very little space, which makes its inclusion a bit

bizarre in this otherwise fairly spare scheme. It is perhaps worth

noting that Whitakker's native North America is the continent best

represented here, but that may reflect the data conveniently available

at the time as much as any cultural bias.

|

Notably, the textbook I sourced the chart from included its own

biome map that doesn't much resemble this, which seems to confirm

that the chart is meant as more a conceptual guideline than a strict

classification system.

|

One odd detail that is borne out, however, is the slight slant in many

boundaries that implies that areas with higher precipitation should

sometimes be classified into colder zones despite no change in average

temperature; this seems to reflect that wetter areas tend to be closer to

the sea or at least have more soil moisture, and so have more moderate

seasons—and an area with a low average temperature needs more extreme seasons to

ensure it has enough of a growing season to support forests rather than

tundra.

Two-Parameter Köppen-Alike

Somewhat inspired by the Whitakker chart, I decided to add a feature to

the koppenpasta update to chart out all a climate map's points by their

average precipitation and temperature, with each point colored by climate

zone.

What's notable is that many of the major boundaries in Koppen do seem

to fall fairly close to straight lines on this chart, and so it might be

possible to approximate a simplified set of Koppen zones based on annual

averages alone. I gave it a go, sticking to straight lines to keep

things simple and only including zones with clear regions they

near-exclusively occupied.

And this can of course be applied back to the Earth data:

It's not terrible given the restrictions, but as per usual we're

lacking some important distinctions due to the lack of seasonal data,

and in general this approach has trouble distinguishing consistently

cool climates such as in mountains from highly seasonal climates such as

at high latitudes. In applying it to other worlds we'd also have to be

wary of losing the assumed correlation between average values and

seasonal variation. But it could have some of that same utility I

mentioned for Holdridge, allowing you to make some broad guesses at the

likely Koppen zones of a world in cases where you only have annual data

to work from, so for that reason it's worth holding onto as an option.

IPCC Climate Zones

This is a system devised by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate

Change

in 2006

to help estimate soil carbon content, with some slight refinement

in 2019. Some of the chosen definitions seem to imply some inspiration from

Koppen, but if so the algorithm has been substantially slimmed down,

perhaps to make it easier to use for those unfamiliar with climate

science and help ensure consistency.

It has 12 zones, divided into 5 thermal categories based mostly on

Average Annual Temperature, except that the tropical category also requires no more than 7 days

with frost and the polar and boreal zones are divided based on the average temperature of the hottest month (the same as tundra in

Koppen), and then most categories are divided into a moist and dry zone

based on whether Total Precipitation exceeds

Total Potential Evapotranspiration. The tropical category is the

odd one out, divided into wet, moist, and dry zones based on

precipitation alone and then adding an additional montane zone based on

elevation.

For my implementation, I've just dropped the tropical montane zone and

the frost days requirements, neither of which are easily available in my

dataset.

It's a somewhat curious result, not aligning particularly well with

biomes, but that's not the stated intent so it's hard to judge how

successful it is in its actual goals.

World Climate Domains

This one is quite recent,

developed in 2020

as a proposed refinement to the IPCC scheme for for use in tracking

conservation efforts. It dividedes the tropical category into tropical

and subtropical and standardizes the water categories across all

zones, with a tweaked moist/dry boundary and an added desert category,

coming out to 18 total zones.

The result is a rather better match to biome boundaries. Various

other issues I've mentioned for other systems still apply here, like

the lack of seasonal data making it difficult to identify areas like

Mediterranean or monsoon climates, and it still has somewhat poor

resolution in semiarid regions, but regardless it feels proper to have

such a straightforward system using this particular combination of

parameters, which other systems like Thornthwaite and Holdridge seem

to somewhat dance around.

|

|

I get the feeling some of the intended colors for this scheme

lost their saturation in the process, but that's something you

can mess with if you like.

|

The paper does then combine these with 4 terrain categories and 8 land

cover categories, both based on direct observation, to assemble a final

map of 431 potential ecosystems; but that's of course not much use to us

here.

Worldwide Bioclimactic Classification System

Another

quite recent system

with very little widespread recognition, though not without reason.

Though it doesn't appear directly derived from Koppen, it has a

broadly similar approach in that attempts to classify climates based

of monthly measurements of temperature and

precipitation, using calculations that are all

individually straightforward. However, in the process of trying

to account for various special cases and complexities in the

boundaries between biomes, the overall algorithm has become byzantine

almost to the point of incomprehensible. Constructing a world map of

bioclimate zones may require calculating over 100 different

parameters, which are combined in various ways to determine 28 main

bioclimate zones, as well as subsidiary classifications of thermotypes

(indicating temperature but also latitude as a proxy for day length),

continentality (indicating seasonal temperature variation), and

ombrotype (indicating the relative prevalance of rain, snow, or

drought).

|

The provided map seems to be scaled to work best as a wall

poster rather than web image; to see it more clearly, follow

the link and look towards the end of the pdf file.

Rivas-Martinez et al. 2011

|

The system uses latitude as part of how it determines the major

bioclimate types (and isn't fully symmetric across hemispheres), on

the logic that this helps represent day lengths. For use on other

worlds one could perhaps attempt to find other measurements of day

length or sun exposure that correlate to these latitudes, but I've

honestly already given up on any attempt to replicate the algorithm;

for all that complexity, the resulting map doesn't appear to be all

that better a match to actual biomes compared to the

alternatives.

Woodward Vegetation Types

This comes from

a 1987 paper

that doesn't explicitly construct a climate classification system,

but instead talks through an attempt to predict major vegetation types

based on climate factors, using the better understanding of ecology

developed since the days of Koppen, Thornthwaite, and Holdridge. It

particularly highlights absolute minimum temperate encountered on

the coldest nights of the year as a measure of thermal tolerances, though

also uses month degrees as a measure of growing season to predict

tundra distribution; the number of degrees C in each month with a positive

temperature, summed across the year.

For the water factor, the paper discusses models of total water balance,

but ultimately determines that in most cases grass and shrubland can be

divided from forst using single

total annual precipitation threshold of 600 mm for most cases and

400 mm for the coldest zones, but for the hottest, wettest regions ,

evergreen and drought-decidious forests are divided based on whether total

precipitation exceeds total potential evapotranspiration.

The paper assembles these factors to predict the distribution of 6 main

vegetation types, though for my implementation I've read between the lines

a bit and extended this to 8, and come up with some appropriate colors

(which I'll admit maybe came out a bit garish). The minimum temperature

data in my dataset doesn't quite correspond well to the absolute minimum

Woodward had in mind, so I've borrowed an approach from the next system

we'll discuss to estimate minimum temperature from coldest month average

temperature.

With modern data, it's far from a perfect match—I'm getting the sense that a lot of old datasets may have overestimated

precipitation—but paper poses this as a preliminary attempt, waiting on better data on

actual vegetation cover to test the central hypothesis—that vegetation cover can be predicted at this level from climate

factors alone—and refine the approach.

Prentice et al. BIOME1 Model

This comes from

a 1992 paper,

with much the same goals as the earlier Woodward paper but benefiting from

more detailed data on Earth's biomes collected in the intervening years, and

more explicitly constructing a complete set of predicted biomes. The

original paper didn't give this system a particular name; some later papers

have referred to it as the BIOME1 model in retrospect because later models

would be named "BIOME2", "BIOME3", etc., but that could be a somewhat

confusing name so I'll mostly refer to it as the "Prentice et al." model.

Building on much the same concepts as Woodward, the authors identify three

main parameters which directly influence patterns of vegetation growth and

competition between plants:

-

Coldest month temperature as a measure of thermal tolerance,

though explicitly as a proxy for minimum temperature, with the

assumed correlation noted, so if minimum temperature data is available,

it can be used directly. Warmest month temperature is also used

to distinguish warm and cold deserts.

-

Growing Degree-Days (GDD) as a measure of growing season,

similar to month degrees in Woodward: Each day is given a number of GDD

equal to its average temperature in °C above some minimum base temperature (so with a base of 5 °C, a day averaging 20 °C would have 15 GDD), and this is summed across the year, excluding

any negative results (so all days below 5 °C would just be 0 GDD). The idea is that the base temperature is the minimum temperature for

growth, and then growth rate is assumed to increase linearly with

temperature, such that the GDD sum represents the total possible growth

during the growing season; which isn't quite true for individual plants

but a reasonable approximation for whole ecosystems. This more direct

measure of the growing season avoids having to juggle different measures

of hottest month temperature or months with sufficient growing

temperature as proxies, any of which are unreliable for different

"shapes" of seasonal temperature change. This model measures GDD

relative to a base temperature of 5 °C for most plants and 0 °C for some desert and tundra shrubs.

-

An aridity factor defined as the ratio of

actual evapotranspiration (AET) to

potential evapotranspiration (PET): Compared to Holdridge's PETR, this is somewhat more reliable

indicator of water availability across different patterns of seasonal

precipitation; PETR cannot distinguish between a climate with sufficient

year-round rains and one with very heavy rains well above PET in one

season but none in another, but AET can never exceed PET (excess

precipitation above PET will store in groundwater or runoff into rivers

rather than evaporate), so a dry season will always lower the average

AET/PET ratio regardless of how much precipitation exceeds PET in the

wet season. This also potentially accounts for water sources other than

precipitation, like stored groundwater or river flow. The trouble is

that AET may be difficult to measure on Earth, but various estimation

methods are possible and climate models more typically include it.

(The paper also refers to soil data but only as part of how they

estimate AET).

Rather than directly linking these factors to biomes, the paper instead

focuses on plant functional types; groupings of plants with

similar adaptations to particular climatological niches. The model estimates tolerable ranges for these parameters for 13

different functional types, with a sorting order to decide which types

can coexist or will be outcompeted in cases where their ranges overlap

(mostly favoring plants with more stringent tolerances requiring high

temperatures and long growing seasons, on the assumption that these

plants are more efficiently taking advantage of these conditions when

they're available because they don't have to spend resources or make

compromises developing tolerance to harsh conditions). This results in

17 possible combinations (9 dominated by a single plant type, 7

featuring more even mixes, and 1 ice/polar desert zone where all plant types are

excluded), defining the predicted biomes.

|

Predicted biome distribution (the scan has not been kind to the

colors but it was the only version I could find).

Prentice et al. 1992

|

The result compares pretty favorably to real biome distribution, though

still with a few oddities. Compared to Koppen, the system lacks a few finer

distinctions such as between Mediterranean and other semiarid regions based

on seasonal precipitation patterns, and the authors do suggest that better

accounting for these patterns might improve accuracy in some areas. Some

biomes like "Cold Mixed Forest" also end up covering a rather eclectic mix

of different parameter ranges, essentially filling the gaps between other

biomes. More broadly, this system is perhaps a tad overtuned to the specific

plant types of modern Earth; though it might be a bit more flexible in

reflecting different plant combinations that might appear in different

climates of the recent past or near future, some of the divisions between

different mixes of deciduous and coniferous forests or warm and cold desert

shrubs may reflect particular evolutionary adaptations of modern plants,

some of which are quite recent.

The choice of parameters also makes it a tad tricky to implement with other

datasets, because measures of PET and particularly minimum temperature can

vary depending on the exact methodology. To keep things simple, here I've

stuck with using coldest month average temperature rather than absolute

minimum, as in the original paper, and I've adjusted all aridity factor

thresholds down by 0.05, as that seemed to give a better match to the

original results. I may play around with some reference ExoPlaSim data to

see if I can find a set of minimum temperature thresholds that work well

there for any future use.

Still, I decided to discuss this system last because it seems to offer the

best model to work from in terms of potential improvements over the Koppen

system. It still draws that link between broad climate parameters and

specific biomes, but it better identifies the parameters that have the most

direct impact based on our modern understanding of plant ecology—and will be the most likely to have that same impact under the different

circumstances of an alien world.

As mentioned, some

later studies

would iterate on the model, reducing the number of plant functional types

but modelling their growth dynamics in more detail and choosing dominant

vegetation type based on their success in maximizing growth rather than a

proscribed sorting order. This is a more direct representation of how

different biomes arise through the competition of different plant types, and

might be intriguing to implement based on ExoPlaSim data at some point

(though the in-built SIMBA vegetation system already works on fairly similar

principles, but a bit simplified and with a single vegetation type), but it

also requires many parameters tuned to the specific behavior of plants on

Earth, which may or may not translate well to other worlds with their own

evolutionary histories. In particular, how plant productivity might be

affect by substantially higher CO2

levels is not clear. It may also be hard to adapt such intensive modelling

of photosynthesis to different potential data sources.

So, though these later models ultimately gained more widespread use and

recognition within academic circles, for our purposes this first version of

the model is the one we should draw inspiration from, balanced well between

models that are over-complex to the point of inscrutability or rely on

detailed modeling assumptions, and simple system that try to reduce

classification complexity but lose a lot of important information in the

process.

Next Steps

If I dug deeper I could probably find a few more classification

systems—I've skipped over several I encountered that were designed only for a

specific region, and so can't be generalized to cover whole planets—but I think the sample we've found is sufficient to work from. In Part

II, we'll finally put some of the lessons gained here into practice.

Great post! What would be the best climate system for a slow rotating planet (more than a month long days), especially if the planet also were to have an obliquity and/or eccentricity that is asynchronous with the day length? Also, what about planets in S-type binaries where the other star causes significant temperate differences to the overall climate?

ReplyDelete*temperature

DeleteWill you continue using the koppenscript moving forward?

DeleteNone of these were really built with use outside of Earth in mind. Koppen, Thornthwaite, and the Prentice et al. model can all accommodate different types of seasonal cycles to varying extents, but are going to run into trouble when there are climate cycles longer than months (which is usually the main sampling period) but don't align with the annual cycle, it's just fundamentally hard to describe that sort of case in terms of regular climate periods. I'm hoping to develop something that's a little more flexible to odd seasonal cycle but will still probably have limitations related to its sampling periods.

DeleteFor things like future climate explorations I'll probably stick to Koppen as the default benchmark classification system, just for ease of comparison, but the koppenpasta update should make it a bit easier to compare different systems from time to time.

SiriusCb of Devientart here, me and a few other people devised an extended Koppen climate system and this is the link to it

Deletehttps://www.deviantart.com/siriuscb/art/Extended-Koppen-Geiger-Climate-Key-2-1116638773

Excuse me if it is my unfamiliarity with the Köppen classification or something about climatology I don’t know. But how can one have tundra or ice sheet when the average temperature rises above 30°C in summer? Should not this allow for lusher vegetation and/or make all the snow melt?

DeleteYou're confusing "hyperthermal" and "hypothermal"

DeleteSorry, everyone can make mistakes.

DeleteI have a question, how low can the CMF (Core mass fraction) of a habitable world be before it becomes a problem?

ReplyDeleteI talked about it a little here https://worldbuildingpasta.blogspot.com/2019/10/an-apple-pie-from-scratch-part-ivc.html#composition but the short version is that it depends on A, how much core mass correlates to the planet's total radioisotope content, and B, how core size influences surface tectonics, neither of which are really known in any detail.

DeleteMaybe for a interplanetary climate classification system it would be best to consider the greatest possible extremes and work inwards. First, mark off the climates that are always too hot, too cold, or too dry for life to grow, then split the rest of the map into regions where those things are true for only part of the year.

ReplyDeleteAlso, for exoplanets and past Earth biomes, amount of light independent of temperature could be another factor to consider for determining biomes (for example, Cretaceous polar temperate forests or above-freezing regions of a tidally locked planet's nightside).

You've somewhat anticipated a couple of my main ideas, I'm focusing a bit on temperature tolerances as a major limiting factor in somewhat the same fashion as the Woodward and Prentice et al models, and then I also want to account for growing season in a way that'll be mostly tied to temperature but with some minimum light limitation as well

DeleteI also thought about this. Here are my thoughts on possible temperature limits of Earth-like life.

Delete1) Of course, the most important hard boundary will be 100° C as the boiling point of water.

2) Next comes the denaturation temperature of 60° C, when protein denatures and starch gelatinizes. In these limits of 60-100° on the surface, in principle, single-celled extremophiles can exist in the presence of liquid water.

3) Perhaps there is also a boundary at 45°/50° C, which separates ordinary plants from extreme ones.

4) On the other side of the spectrum, of course, there is a boundary at 0° C.

5) In the absence of snow, lichen can grow on stones, one of the species of which, for example, can photosynthesize at -24° and grow at -10° C. Therefore, perhaps there are biomes of such (lichen) subzero tundra.

6) It may also be possible to distinguish biomes of "glaciers with snow algae" growing on snow at a temperature of 0 - 10 ° C. They may be a transitional biome from tundra to a real glacier.

7) As the lowest possible temperature for life, I can think of the freezing temperature of antifreeze-glycerin at -46 ° C during the warmest period. Earth-like life will definitely not be able to live colder than this, no matter how hard it tries to adapt.

All the biomes I listed above are not needed for Earth-like planets, but may be useful for extreme ones.

I think your fifth alternative should be considered a type of desert considering its low biological productivity. Some ice-free parts of Antarctica are already considered this. Parts of northern Greenland and some areas on nearby Canadien islands probably also qualify.

DeleteYour third suggestion is a good reason for the polar grasslands of my high axial tilt world. It has a significantly thicker atmosphere 0,0009 atm of carbon dioxide. Lowlands within 10° of the poles have seasons so extreme they largely lack penial plants. They even have two plant communities succeeding each other over the course of the year. First, there is a spring community coping with 0 ‒ 30°C. Second, there is a summer community growing at 25 – 60°C (preferring 30 – 55°C). There is no autumn community since it gets too dark to photosynthesize too quickly. Animals above a certain size are also missing from these grasslands. The ones found there are either small burrowers or migratory fliers. The later spend the peak of summer in the nearby highlands were it rarely gets hotter than 45°C.

DeleteIf it is above freezing but too dark for much in the way of photosynthesis I think fungi (or the local equivalent) would take over. This is what happened on Earth in the years after an asteroid hit the Gulf of Mexico 66 million years ago. Dead organisms which had not burned up were broken down by fungi wherever it was warm enough for them.

DeleteAfter an extinction they may feed on the remaining dead material and organic matter in the soil for a while, but that's not a sustainable ecosystems, they're just feeding on the leftovers of photosynthetic production and would run out at some point if conditions hadn't improved; so in a permanently dark environment they wouldn't have a comparable source of energy or nutrients.

DeleteI know enough about biology to have already realised this. My idea presupposes darkness without cold to be seasonal. However, I think tidally-locked planets would have a limited light zone. In this zone the sun is never visible but some light leaks in though the atmosphere. This might allow form some vegetation like the small plants growing in the shade of larger ones. If there is too little light life would be limited to what can be based on chemosynthesis.

DeleteWhat’s the best way to encourage a lot of wet climates and a permanent water cloud cover while maintaining a 70/30 water/land ratio and no tidal-locking?

ReplyDeleteSome things that may help are high global temperatures, many small landmasses instead of large ones, more axial tilt rather than less, and longer rather than shorter day length.

DeleteSubstantially longer days seems to lend itself to a broad wet region across much of the low and mid latitudes, but I'm not sure there is any way to get actually permanent cloud cover.

DeleteI seriously doubt “permanent water cloud cover” is possible. That sounds something like how they imagined Venus before they found out the surface temperature was above the melting point of lead.

DeleteOne thing I’ve also noticed when looking at the habitable Mars post is that how hot deserts/steppes are distinguished from cold deserts/steppes can change. On the standard Köppen model, hot deserts/steppes have to have an overall mean temperature over the year of >18°C (but not necessarily every month like in tropical climates), otherwise they’re considered cold deserts/steppes. Whereas on the koppenscript for ExoPlaSim, the distinction is more like the temperate/continental, with hot deserts/steppes having every month’s average being >0°C, and cold deserts/steppes having at least 1 month’s average <0°C. I’m not sure why the distinctions changed? The latter way of interpreting cold deserts/steppes means they are impossible to occur in seasonless worlds.

ReplyDeleteYeah, as mentioned there are a lot of such minor variants on the Koppen-Geiger formula, including different C/D thresholds, different Xs/Xw/Xf algorithms, different arid zone threshold algorithms, different treatment of Am,As, and Aw, etc., so there's not really a single universal standard you'll see used in every study. I've used the 0 C winter threshold for hot/cold arid zones in all the maps I've produced because I tend to think cold winters are more likely to have some common biological influence than the average temperature threshold, which so far as I can tell is related to the particular competitive advantages of C3 and C4 grasses in the modern atmosphere.

DeleteThe Mars köppen maps are very fascinating, but I couldn’t help noticing how much of it is dominated by hot desert and steppe climates. Given the conditions of a habitable Mars, wouldn’t some of those regions be more realistically classified as ‘temperate’? It’s an interesting reminder of how different climate models can shape our interpretation of weather and also biological processes.

DeleteBy the way, I sent you an email about a commission—can’t wait to see how a habitable Venus simulation would turn out on ExoPlaSim!