An Apple Pie From Scratch, Part V Supplement: Tectonics: Using Gplates

This post is a supplement to Part Va;

that post described how to simulate plate tectonics conceptually, in terms of

what overall patterns of drift, collision, rifting, and so on to expect. This

post will be more technical, describing how to use Gplates to turn that concept into a tangible reality. Gplates is primarily

designed for use by geologists, and by the standards of similar programs it is

amazingly intuitive; but users from the worldbuilding community usually find it

awkward to use at first. I still hold that playing around with the program is

the best way to overcome that, but hopefully this tutorial will give you a bit

more direction.

If you'd rather go through this in video form, friend of the blog Artifexian has been working on replicating this tutorial in his "Artifexia" video series (starting with Part 9).

If you'd rather go through this in video form, friend of the blog Artifexian has been working on replicating this tutorial in his "Artifexia" video series (starting with Part 9).

- Basics

- Making and Moving Plates

- Making a Rift

- Splitting a Feature

- Making a Rotation File

- Moving the Plates

- Checking and Finalizing Plate Motion

- Making Flowlines

- Adding Ocean Crust

- Adding Subduction Zones and Island Arcs

- Complex Plate Interactions

- Importing Rasters

- Splitting Comoving Plates

- Making a New Plate

- Subducting Ocean Crust

- Colliding Continents

- Splitting Plates After a Collision

- Marking Resulting Features

- Finishing and Exporting

Basics

Basic use of the program, and the procedure to draw, create,

and save “features”.

Startup

Installation of Gplates is straightforward: Follow the

instructions below the download link

for your operating system. I’m using a Windows PC to make this tutorial, so if

you have something else you may find that the appearance and shortcuts are

slightly different.

Once you have it installed and open, you’ll see a lot of

available tools and options, but many of these are designed for reconstructing

Earth’s tectonic history based on geologic evidence, and aren’t useful for

building a new world’s history. Don’t worry about what something like the

“Hellinger” tool does, as we won’t be using it.

The window should have a list of toolsets on the right side,

which can also be selected with hotkeys from “1” to “7”; some

individual tools have their own letter hotkeys (though similar the same hotkey

may select different but similar tools, depending on which toolset you have

open). We’ll mostly just be using the top 3 and the 5th sets.

The “View” toolset (hotkey “1”) includes the

movement tools, but even with other tools open you can hold down the “ctrl”

key and drag the globe or map with your mouse, and use your mouse scroll to

zoom in and out.

Most of what we’ll be doing is handling features:

sets of points, lines, or polygons on the globe’s surface.

The “Feature Inspection” toolset (“2”) includes tools to select

and edit features, the “Digitisation” set (“3”) includes tools to

create new features, and the “Pole Manipulation” set (“5”)

includes tools to move features.

One tool you may use a lot is the Measure tool (“S”),

which allows you to click 2 points on the globe to see the distance between

them, even if the planet’s size differs from Earth’s (by altering the “Earth

radius” value in the upper right in kilometers).

Timescale

The bar along the top handles the timescale, on a scale of

millions of years before the present (Ma); Gplates isn’t built to

handle timescales extending into the future. By default the scale only extends

to 200 Ma, but you can select the number in the upper left and enter a higher

value (you can also change the default timescale permanently in the

preferences); I used 1000 Ma for modeling Teacup Ae, but it’s probably more

prudent to use at least 2000 Ma to give yourself plenty of breathing

space, especially if you want to use longer supercontinent cycles or have an

endpoint later in the second cycle than Earth or Ae.

Once you’ve set that, you can use the scroll bar to look

through your world’s history and use the play button to see features moving

once you’ve added some. But when adding or moving features it’s best to do it

at particular time steps, so you should type in a precise time.

To get started making features, set the time all the way

back at the start (2000 Ma, if you’re using that).

Making your First Supercontinent

We’ll start out simple: A cluster of cratons and a

landmass enclosing them.

To make a craton—or any other polygonal feature—select the “Digitise

New Polygon Geometry” (“G”) tool in the “Digitisation”

toolset (“3”).

Then draw an object by clicking on the globe to draw

vertices; the tool will draw in lines between them, including one from the last

vertex you place to the first to close the loop. “Ctrl-Z” will delete

the last placed vertex like you’d expect, and you can also use the “Move

Vertex” (“V”), “Insert Vertex” (“I”), and “Delete

Vertex” (“X”) tools to alter the feature as you create it, or analogous

tools in the “Feature Inspection” toolset to alter the feature after

you’ve created it.

Cratons in real life have ill-defined and malleable borders,

so don’t worry about shape too much beyond “roundish”, “oblong”, “curved”, and

so on. Size varies quite a bit, but we’re only worried with the largest ones

here, so somewhere around 1-4000 km is about right.

Once you’ve drawn it, select “Create Feature” in the

lower right.

This will bring up a new window asking you to select a feature

type from a long list. Most of these are just different names for features

that behave identically in the program, but a few do behave differently so just

select “Craton” and “Next”.

Next we have to define some properties:

- Leave “Geometry Property” on “Outline”. We shouldn’t ever need to alter this property from the default for any of the features in this tutorial.

- “Plate ID” is used to identify objects that are on the same tectonic plate, and so move together. We’ll discuss how to make that work later, but for now let’s just give each of our cratons its own plate ID, even those we want to initially move together. The IDs are numbers, and we shouldn’t give any features an ID of “0”, as that’s reserved for the immobile “rotation” axis. Let’s give this first craton an ID of “100”.

- “Begin (time of appearance)” and “End (time of disappearance)” define the period of the planet’s history over which this feature exists, and we’ll play around with it later as features are created, destroyed, or change. But the cratons should persist throughout this whole period we’re simulating so select the options for “Distant Past” and “Distant Future”, indicating the feature should exist at all times even if we changed the timescale.

- “Name” is, of course, just a name to keep track of the object. Multiple objects can have the same name, but in this case let’s name this feature “Craton A”.

- Important note: I've heard from some users that using non-Latin characters (letters not used in English, like Cyrillic characters) can cause issues, such as files not saving properly. This should only apply to the names of feature collections and project files, but it's probably best to just stick to Latin characters everywhere. It seems to apply to the folders the files are held in as well, so make sure your whole filepath contains only Latin characters if possible.

All that done, press “Next” to continue. We don’t

need to do anything with the next window, so press “Next” again.

Finally, it’ll ask us to place the feature in a feature

collection. The appearance of features in a collection are altered

together, so we’ll use these to arrange features we want displayed in a similar

way; cratons, continents, subduction zones, etc.

Because this is our first feature, our only option is to “Create

a new feature collection”. Press “Create and Save”.

This will open the “Manage Feature Collection”

window, which for now contains only your new feature collection. Press “Save

As” to name your feature collection (let’s call this one “cratons”; again, avoid non-Latin characters)

and save it. Each feature collection will be saved as a separate file, so

you’ll want a dedicated folder to keep them all together.

After that you can close your window and you should see your

craton has a nice blue color. These colors are assigned by plate ID, so as you

add each craton with a new ID it should have a different color (though there

are a limited number, so eventually you may get duplicates).

Keep adding cratons in the same way, clustered together but

with some space between them. Give each a new plate ID, and rather than

creating a new feature collection for each craton, select the existing “craton”

feature collection (the window will list it with the full file path) and press

“Create” rather than “Create and Save”. For a world with

Earthlike land area and tectonic activity around 8-12 cratons is probably

ideal, but to keep things simple in this tutorial I’ll just make 3; In addition

to craton A, cratons B and C, with plate IDs 200

and 300.

When you have all your cratons down, you can draw another

polygon encompassing all of them, which will be your initial supercontinent.

It’s reasonable—encouraged, even—to have large stretches of land outside the

cratons.

One issue you might run into is that if your

supercontinent’s longest axis extends more than halfway around the planet, GPlates

won’t be able to tell which part of the world is inside the polygon and which

part is outside, which will create issues with filtering rasters and so on.

Fortunately, this should be fixed when we break this supercontinent apart later

on.

Create this feature like you did with the cratons, but with

a few different steps:

- For feature type, select “ContinentalCrust” rather than “Craton” (I’m not sure this actually amounts to anything, but it’s good to keep things organized).

- This continent won’t be moving independent of the cratons, so rather than a new plate ID we’ll just give it the same ID as one of the existing cratons—say, that of the first craton, 100.

- We’ll name it, say, “Continent ABC”, after the cratons it contains.

- We’ll make a new feature collection for it, “continents”.

And lo, we have our first supercontinent. Before you do

anything else, select the “Choose Feature” tool (“F”) in the “Feature

Inspection” set, select your continent, and then switch to the Measure

tool (“S”). The info pane on the right will include a measure of your

continent’s area. Because your supercontinent is the only landmass on the

planet, this will be the total land area of the planet.

Compare this value to the total land area of the planet,

which is [ 4 * π * (radius)2], or 510 million km2 for Earth’s

radius. Recall that a planet with 1/4 of its surface area covered in

continental crust roughly matches Earth’s condition 1 billion years ago, and

modern plate tectonics may be impossible once over 1/2 the planet’s area is

covered in continental crust. My small supercontinent occupies less than 5% of

the area of this planet, which is still reasonable if you don’t want much land

area.

To help us keep track of things, you can select “Window”

-> “Show Layers” from the toolbar on top to open the layers window.

This lets you make feature collections visible or hidden and alter their

stacking order (higher feature collections appear above lower ones) and also

has a dropdown menu for altering the appearance of features in each collection:

You can “Fill polygons” to fill the polygon features with their outline

color, alter the “Fill opacity”, and the “Set Draw style…” menu

can alter the color set, or set all features in the collection to the same

color, or color them by age, etc.

For now I’ve set the continents to be filled with white at

an opacity of 0.2, and the cratons to be filled based on their plate ID with an

opacity of 0.5, which will help us keep track of land areas once we start

adding ocean crust and other features.

Saving the Project

One last thing we should do now that we’ve got some features

down is save the project, which we have to do in two steps. Open “File”

-> “Manage Feature Collections”, and in the window press “Save All

Changes”. The list of features should change from red to white. Then open “File”

-> “Save Project As…” and save it in the same folder as your feature

collections. This is the file you’ll open to get the project back, but all the

feature collection files are necessary for the project, so keep them packaged

together.

Once more, remember that GPlates may have issues with non-Latin characters in its filepaths.

Once more, remember that GPlates may have issues with non-Latin characters in its filepaths.

Making and Moving Plates

This is the core process of this simulation, and the main

reason for using GPlates. It’s a bit awkward at first, but with repetition

you’ll get used to it.

Making a Rift

Obviously, this supercontinent is not long for this world;

we’ll start the simulation by rifting it apart. Supercontinent rifting can be a

multi-step, complicated process, but in this case we’ll just do a clean split

down the middle, sending Craton A west and the other cratons east.

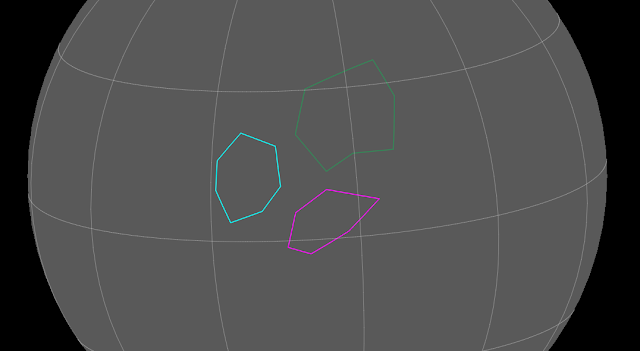

|

| Red line and arrows added by me outside GPlates |

Whenever I rift a continent apart, I like to draw the rift

as a distinct, immobile feature, to help me keep track of how the continents

move compared to the initial rifting spot. You can do this by selecting the “Digitise

New Polyline Geometry” tool (“L”)—not the polygon tool—and placing a

line across the center of the continent. In this case you’ll see that

subsequent vertices are connected by the program, but not the last to first.

Remember that these rifts are formed by the joining of triple junctions, giving

them an overall zig-zag shape, and that the rift shouldn’t pass through any of

the cratons.

Select “Create Feature” as with any other feature, and proceed through the windows:

- Set the feature type as “ContinentalRift”.

- Set the plate ID as, say, “1”, which I reserve for immobile objects (you could put them in 0 with the rotation axis, but I prefer to just leave that alone).

- Unlike the previous features, we’ll have this one begin when rifting begins (2000 Ma in this case) and then continue into the distant future (this doesn’t matter much at the start of the timeline, but it’s good practice for when we make more rifts later).

- For naming, I tend to just name small objects like rifts, subduction zones, and island arcs after the year they form, e.g. “rift 2000”, which helps keep track of their age if we have to replace the feature later.

We can also make a new feature collection for rifts, and

give them a color like red to stand out.

While we’re on that, we can also create failed rifts,

which don’t split the landmass but can cause new rifts and river valleys later

on, at each of the triple junctions. We’ll use the polyline tool and make the

feature type “ContinentalRift” like the main rift. But we want these

features to move with the continents, so we’ll assign each the same plate ID as

the nearest craton on the same side of the nearest rift, tying the rift’s

motion to that craton.

If you can’t remember the plate ID, you can use the “Choose

Feature” (“F”) tool to select a feature and see some info about it

near the bottom of the window (it’ll display the info for all objects near

where you’ve clicked, so don’t worry about selecting the exact feature). Don’t

be alarmed that the rift you’ve drawn disappears when you select this tool;

it’ll appear again when you return to the digitise tools.

Create the feature with that plate ID, and beginning at the

same time (2000 Ma) as the main rift. Let’s also create a new feature

collection for failed rifts, and give them a more muted silver color.

Splitting a Feature

So that tells us where the rift is, but if we’re going to

split this supercontinent into 2 continents, we’ll need more than the one

continent feature we have. There’s no tool for cutting polygons apart (there is

one for polylines), but a couple tools we can use to make new features.

First off, select your feature (If you ever have trouble

selecting from multiple features, use the list at the bottom) and select the “Clone

Feature” option on the right.

Place it in the “continents” feature collection when

prompted, and you’ll get a new feature identical to the original continent,

including plate ID and beginning and ending times. We gave the supercontinent

the same plate ID as craton A, so we’ll convert this clone into the section

containing that craton. Select the “Move Vertex” tool (“V”) on

the left, making sure you’re in the “Feature Inspection” toolset (“2”).

You should see the vertices of the continent as white

points, which you can now click and drag to move. Leave those on one side of

the rift unmoved, and move those on the other side to match the rift. Don’t spend

too much time trying to line them up exactly; it’s not as if actual continents

perfectly preserve their shape after rifting anyway.

If, like me, you run short of vertices, you can use the “Insert

Vertex” (“I”) tool to add more; if you end up with spare, you can

use the “Delete Vertex” (“X”) tool to remove them. Ultimately,

you should end up with a feature encompassing the entire former supercontinent

on one side of the rift.

Return to the “Choose Feature” tool (“F”) and

select “Edit Feature” (“ctrl-E”) on the right.

This will bring up a window allowing us to alter some of the

feature’s properties. In particular, we want to change the “gml:validTime”

property; un-select “Distant Past” and set the feature to begin at 2000

Ma, when the supercontinent rifts. To keep things straight, we should also

change the name to “Continent A” to match the cratons it contains.

Repeat the same process again to create a “Continent BC”,

but this time when editing the features also change the plate ID to match that

of one of the cratons it contains—say, 200 for Craton B.

Finally, select the original Continent ABC feature,

and set it to end at 2000 Ma. This doesn’t matter much at the beginning

of the simulation, but when you repeat the process for rifts later in the

simulation, the result will be that you have one feature up to the time of

rifting that instantly splits into two objects at the time of rifting that can

then drift independently.

In principle we could also do this in reverse to merge

features, But I prefer to preserve boundaries in case there’s a later rifting

event that breaks along that same boundary, and also because it may help in

drawing topography later on.

Making a Rotation File

To move plates over time and record these movements, we

first have to create a rotation file.

Open up a basic text editor (I like to use Notepad++) and

input these lines (you don’t actually need more than one space between columns,

but it helps keep things organized):

100 2000.0 90.0 0.0 0.0 000 !

Each line describes the position of a plate at a given point

of time, and each column describes some aspect of the plate or motion, like so:

Plate ID

|

Time

|

Latitude

|

Longitude

|

Angle

|

Conjugate Plate

|

Comment

|

100

|

0.0

|

90.0

|

0.0

|

0.0

|

000

|

!

|

100

|

2000.0

|

90.0

|

0.0

|

0.0

|

000

|

!

|

- Plate ID is, of course, the plate ID that is being described. All features in each plate ID always move together.

- Time designates the time at which the plate has this position. The important thing to remember is that gplates will read this file from the present backwards, as opposed to our simulation process with proceeds from the past forwards; this will come up a few times in later steps.

- Latitude, Longitude, and Angle describe the position of the plate in terms of an Euler rotation. You don’t have to worry too much about what this means for now, but in short latitude and longitude describe the position of a rotation axis on the globe, and the angle describes the rotation of the plate around that axis. The rotation at time 0.0 should always have latitude 90.0, longitude 0.0, angle 0.0, indicating no rotation (changing it will cause issues with some features later). Presuming we want objects at the start of the simulation to begin where we draw them, the plates should have the same rotation at the start (time 2000.0 in this case).

- Conjugate Plate allows us to define the position of one plate relative to another. Entering 000 defines the position relative to the unmoving “rotation” axis, and so basically allows us to move that plate independently. Setting it to another plate ID will cause this plate to follow all that plate’s movements (it can still have some movement of its own relative to that other plate). So, for example, if we want Craton C to follow Craton B at the start of the simulation, we can set the conjugate of C’s plate, 300, to be B’s plate, 200. Now when we move Craton B, C will follow it.

- Comment allows you to place any notes after it; name of the plate, events happening at a certain point, etc. Even if you don’t use it, you still need to place the exclamation mark.

So here’s how that all appears for my supercontinent, with

Continent A splitting from Continent BC:

Once you’ve got all that, save the file alongside your

feature collections as “rotation.rot” (set “save as type” to “all

types” or save it as a .txt file and rename it).

Back in GPlates, select “File” -> “Manage

Feature Collections” (“ctrl-M”), and then press “Open File…”.

Find and select “rotation.rot” and open it. It should load in as a new

feature collection.

Moving the Plates

Finally, the exciting part. The basic process here is to

move time forward in timesteps, move all the plates around, and then move

forward again.

I like to use a timestep of 50 million years—long enough

that we won’t have to do too many to complete the simulation, not so long that

we’re losing important details. If there’s a complex collision I might slow

down to 10 My timesteps in that area, and of course you can decide what to do

for yourself.

Whatever you decide, set the timeline forward by one

timestep—to 1950 Ma in this case—and select the “Pole Manipulation”

toolset (“5”). Then select “Choose Feature” (“F”) and

select a feature with the plate ID of the plate you want to move. Select “Move

Pole” (“O”) and then “Enable pole” on the right. A sort of

round arrow should appear pointing out of the north pole.

Using this tool and the “Modify Reconstruction Pole” tool

(“P”), you can move plates around using Euler rotations, like I

mentioned before. These are a bit awkward to get used to, but using them helps

give you realistic plate motion. In essence you move the pole, and then rotate

the plate around that pole. As you do, the program shows you a “ghost” of where

features in that plate will move to.

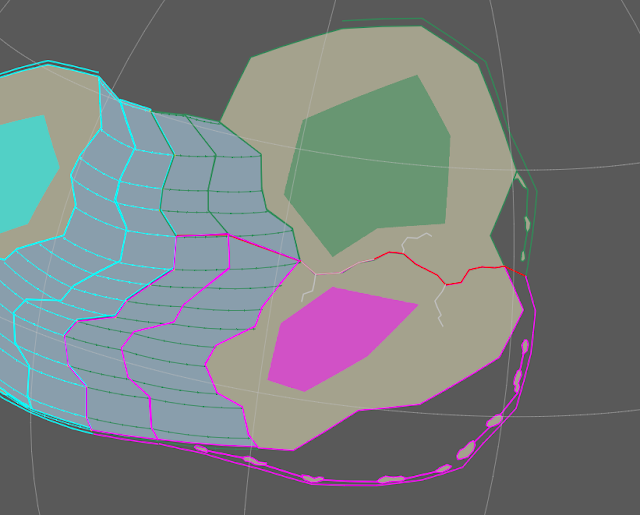

|

| Again, red lines and arrows added outside GPlates |

You can select “Highlight children” on the right so

that the ghost also includes features in other plates tied to move with the

plate you’ve selected, and “Reset Rotation” to undo any movement you’ve

done and start over.

Linear motion and rotation always accompany each other on

the surface of a spherical globe, but you’ll want more of one or the other in

different situations. Placing the rotation pole close to the center of your

plate will give you more rotation, and placing the pole far from the center

will give you more linear motion (there is only one pole shown, but the

rotation axis it represents passes through to the other side of the planet, so

functionally the furthest the pole can get from the plate’s center is 1/4 of

the way around the globe).

You can also move the plate with the pole at one point, move

the pole, and then continue moving the plate.

|

| Blue arrow added outside GPlates as well |

If a plate extends across a large portion of the globe,

movement in one part will manifest as rotation in another, and vice-versa, so

you can’t have one without the other; this tends to limit the lengths of single

divergent or convergent boundaries.

Once you’ve decided on where you want to move the plate,

select “Apply” on the right. Press “Okay” on the window that pops

up, and you should see the features in the plate pop over to where you’ve moved

them.

If you scroll back in the timeline, you can see the plate

smoothly move over to its new position.

Checking and Finalizing Plate Motion

So that's how to move plates, but is the motion realistic? You can

consult the main tutorial

for general patterns, but we can check the speed of plate motion right now.

Select “Utilities” -> “Open Kinematics Tool…”

from the top (“ctrl-shift-K”). In the window that pops up, put in the

plate ID of the plate you want to analyze, set the timescale to the period you

want to look at, and set the “Display type” to “Velocity magnitude”.

You should get a graph of average velocity magnitude over time in the window

for that plate, and you can mouse over it (or check the table above) to see the

velocity over the period of motion in centimeters/year.

I talked about plate speed in the main tutorial, but in short

here are typical values:

Situation

|

Subducting Ocean

|

Recent Subduction Collision

|

Active Margin Continent

|

Passive Margin Continent

|

Plate speed (cm/year)

|

8-20

|

6

|

3

|

<1

|

So my motion for Continent A at ~3.4 cm/year is fast but

reasonable. If you find that your motion is unrealistic, or for whatever reason

you want to change it, then you can move the plate again and apply the new

rotation; so long as you do this at the exact same time as you

originally applied the rotation, it will overwrite that previous rotation, and

the plate will move smoothly to this new position when you look back through

the timeline (you can also reload the “rotation.rot” feature collection, which

will reset all rotations back to the last time you saved them to the file).

To finish up, one issue with simulating plate movement

forwards while GPlates reads the rotation file backwards is that, when you move

the timeline forward again by another timestep, the plate will start shifting

back towards its original position. This isn’t too problematic at the start of

the simulation, but can start getting annoying as you approach the end.

Luckily, it’s not hard to fix: First, open “File”

-> “Manage Feature Collections” (“ctrl-M”) and save the “rotation.rot”

feature collection, which should remove the red highlighting.

Then open the “rotation.rot” file in a text editor

and find the line showing the latest position of the plate other than at 0.0

Ma. Copy this line above it, and change the time column to “1.0”. This

gives that plate the same position at almost the end of the timeline as it has

at the latest point we’ve simulated to (while still not messing with the

position at 0.0, which could cause issues).

Save “rotation.rot” in your text editor, go back to

GPlates, and in the “Manage Feature Collections” window, reload the rotation.rot

feature collection to update it to match the file.

Checking through the timeline, you should see that the plate

no longer moves between the last time at which you’ve moved it and 1.0 Ma, and

then snaps back at 0.0 Ma to its original position. You’ll have to do this

again, at each timestep, for every plate you move in that timestep (you can

leave alone plates that are moving with their conjugate plate but don’t move

relative to the conjugate plate in that timestep). This can be a bit tedious,

so it’s up to you when it’s necessary.

Making Flowlines

Flowlines are useful features to visualize the opening of

new ocean basins and keep track of the mid-ocean ridges. To make one, let’s go

back one timestep to the start of the simulation. Select the rift feature you

made, and select “Copy Geometry to Digitise Tool” on the right.

Then select the “Digitise New Multi-Point Geometry” tool

(“M”) to switch the feature from a polyline to points, and press “Create

Feature” (If for whatever reason you don’t have a rift feature to copy, you

can just select this tool and trace the boundary between diverging plates).

- Select “Flowline” for the feature type.

- Input the plate IDs of the landmasses on either side of the rift (e.g. 100 for Continent A and 200 for Continent BC here). Which is on the left or right doesn’t matter, and the plate IDs don’t have to be those of the objects directly on either side of the rift, though that’s generally a good practice. The plate IDs also don’t have to those of independently moving plates; you can select one being moved by its conjugate plate.

- Have the feature begin at the point of rifting (e.g. 2000 Ma in this case).

In the next window, select the “Add” option. This

will open another window. In the “Insert multiple times” section, input

a “From” time when the rifting starts, a “to” time far later, and

for the “in steps of” option put a some fraction of your timestep; for a

50 My timestep, 10 My works pretty well. Press “Insert” and you

should see a list of times appear in the window above.

Press “OK” and “Next”, and create a new

feature collection for flowlines. When all that’s done, you should be able to

move the timeline forward and, as the landmasses move apart, a series of lines

appears connecting their coasts. The yellow dots in the middle show the position

of the mid-ocean ridge; note how, because the continent motion isn’t

perfectly symmetric, the mid-ocean ridge moves off the position of the original

rift.

One good application of flowlines is that they can help

check for unrealistic plate motions: Adjacent flowlines generally

shouldn’t pass over each other (to a small extent deformation of the crust can

accommodate minor examples of this), and they should never pass over existing

sections of crust, except where subduction is occurring; as a divergent

plate boundary spreads, the flowlines can help you see when it is no longer

possible to have spreading along the whole boundary and you need to add a

subduction zone.

Ideally we could place flowlines first and then see how they

appear when we move plates, but for whatever reason adding rotations to the

plates that flowlines are attached to can cause them to oddly “drift” (it seems

to happen specifically when an existing rotation is overwritten). You may find

that you have to delete and then recreate the flowlines fairly frequently.

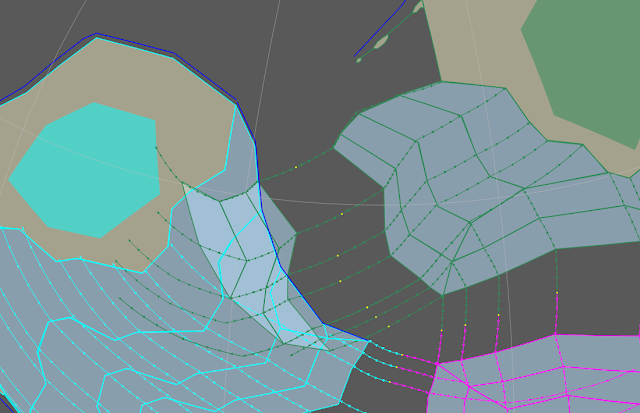

|

| An example of both unrealistic plate motion (flowlines overlapping each other and the continents) and the "drift" I mentioned (the endpoints should be on the coastlines). |

Adding Ocean Crust

Another benefit of the flowlines is they can be used to add

sections of ocean crust. Select the flowlines feature, copy the geometry, and

then select the “Digitise New Polygon Geometry” tool (“G”). This

will give you the start of a polygon with one edge on the mid-ocean ridge, and

then you can trace over the nearby coastline to get a polygon encompassing all

the new ocean area opened on one side of the mid-ocean ridge (GPlates will add

new vertices to one side of the existing line, so make sure you start on the

correct side to get a neat closed loop; and again, don’t spend too much time

trying to exactly line up your new polygon with the coastline).

Press “Create Feature”:

- Select “OceanicCrust” as the feature type.

- Give it the same plateID as the continent it’s attached to.

- Have it begin at the current point, one timestep after the rift opens, as it wasn’t fully formed until now (this means that between timesteps there will just be some open space between the rifting continents, but that’s unavoidable).

- As with small features, I like to name ocean crust pieces after their date of formation, e.g. “ocean 1950”; this gets very useful in keeping track of their ages later on when it may be necessary to replace the features.

Finish creating the feature with a new feature collection

for ocean crust. Follow the same process on the other side of the rift, adding

it to the same feature collection, and we now have our new ocean basin filled

with fresh crust.

In terms of display, it’s useful to have the ocean crust features

retain the colors of their plate IDs to tell them apart when there’s many

crowding the ocean, but perhaps we should give them a very light fill—say, 0.1

opacity.

Going forward one timestep and moving the continents again,

the process of adding new ocean crust will be the same, but this time trace out

the boundaries of the existing ocean crust pieces, rather than the coastlines.

You shouldn’t have overlapping sections of ocean crust except where one is

subducting under another.

Creating the feature is much the same process:

- Give it the same plate ID as the crust section it’s attached to.

- Have it begin at the end of the current timestep, and name it accordingly.

- Put it in the same “ocean crust” feature collection.

And so on, as the ocean continues to grow.

Adding Subduction Zones and Island Arcs

Mid-ocean ridges are only one part of the equation, of

course; as new crust created here, old crust must be subducting elsewhere. Trying

to figure out how subduction would work in the initial ocean without any

initial ocean crust would be a tricky task, but luckily it’s normal for a

supercontinent to start surrounded by subduction zones just before it rifts; we

can just let those subduct away the old oceans.

Return to your first timestep, and look back and forth

through the simulation to try and get a sense of where the leading edges of

your continents are.

|

| Given motion of the plates (red arrows), I've marked out the leading edges (blue lines) |

Then go back to the start of that timestep, when the continents

start moving, and use the “Digitise New Polyline Geometry” tool (“L”)

to mark out subduction zones just offshore of your continents along their

leading edges. They need not be directly offshore, mind; you can have some

excursions away from the coasts, or pass across the mouths of large bays, and

at the ends of the leading edges of the continent you can have them extend

further outward, so long as they’re still perpendicular to the motion of the

plate.

Press “Create Feature”:

- Select “SubductionZone” for the feature type.

- Give them the plate ID of the nearest craton on the continent they’re formed by.

- Have them begin at the same point you make them—at the beginning of the timestep where the continents start moving, and name them accordingly.

Make a new feature collection for them, and there we are:

Fresh new subduction zones, which should appear as lines colored by their plate

ID.

These subduction zones will, of course, cause volcanism and

the formation of new continental crust on the overlaying plate. Along the

continental coasts this will cause orogenies, but we’ll worry about those

later. A more immediate concern is the creation of island arcs at sea.

My rule of thumb is that island arcs form one timestep—50

My—after the subduction zone first appears (the one exception is at the

very end of the simulation in the last timestep, when even newly formed

subduction zones should get small island arcs). So let’s move forward one

timestep, and then select the “Digitise New Polygon Geometry” tool (“G”).

On the trailing side of any subduction zone in the ocean, start drawing

out an arc of small islands, each no more than a couple hundred miles across.

Rather than tediously drawing a lot of individual features, I

prefer to draw the islands as one object by first drawing one side (the “bumps”

are islands and the straight sections the gaps between them)…

…and then drawing the other side, tracing over the

connecting lines between islands to make bars that should hopefully be too thin

to see on the world map.

Create the feature:

- Feature type “IslandArc” (or ContinentalCrust, it doesn’t really matter)

- The same plate ID as the subduction zone that formed it.

- Beginning at the current time, one timestep after the subduction zone appeared.

- And finally, give it its own feature collection.

And though I’m calling these “island arcs”, they can include

spurs of land attached to nearby continents where the subduction arc passes

from coastline to ocean.

Once we make an island arc, we don’t need to touch it again

unless it’s involved in a collision or rifting event. Actual island arcs

develop more gradually—appearing fairly early and growing over time—but what

we’re drawing here are more abstract representations of island arcs than actual

mappings of islands. Once you’ve finished the simulation, you can edit the

resulting map outside GPlates to add larger islands to old arcs.

One thing to remember about subduction zones is that they

don’t only appear when a continent rifts apart or changes direction; If we say

that these continents are subducting some of the ocean to their south, then as

they move apart that subduction zone will spread along the new ocean’s southern

border. So with each timestep, we have to add new sections of subduction zone

and island arcs on that boundary.

This also has the nice tendency of naturally forming long

arcs, because of how the plates move across the globe.

Complex Plate Interactions

Now that we have a feel for basic plate motion, let’s go through

all the types of rifting, collision, and subduction you should encounter in

simulating tectonic motion.

Importing Rasters

We’re about to move into some more complicated procedures,

where it’s useful to keep track of every individual feature, so we’ll just take

a quick detour to input some rasters to help that process along.

Rasters are just visual overlays on the globe. Any map in an

equirectangular projection—an even grid of latitude and longitude, which is

twice as wide as it is tall—can be imported as a raster; this is a pretty

useful function for gplates even when you’re not using it to simulate plate

motion.

But in this case we’ll just use flat color rasters, like

this 1000 by 500 pixel beige image that will be our “land” raster:

In Gplates, go to “File” -> “Import” ->

“Import Raster…”, and select your raster. The program accepts a pretty

wide range of image file types; I used a .png in this case. Give the raster

band a name if you like, leave the default options on the “Georeferencing”

window, and create a new feature collection.

Once you’ve done all that, you should see the whole world

colored by your raster. Select “Window” -> “Show Layers” (“ctrl-L”)

if you don’t already have the layers window open, and find your raster on the

list. In the “Inputs” menu, find “Reconstructed polygons” and

press “Add new connection”.

From the dropdown menu, select “continents”, or

whatever you’ve named the feature collection containing your continents. This

will now restrict the raster to only appear within the polygonal features in

that feature collection.

Set the rasters “Opacity” down to “0.5” so

that we don’t obscure any underlying features.

Add all your features containing distinct landmasses (just island

arcs for now, but microcontinents, accreted terranes, and continent

fragments later on). Then, in the layers for the continents feature

collection, you can un-select “Fill polygons”, set the “Fill Opacity”

back to ”1.0”, and use the “Set Draw style…” menu to set it back

to color by plate ID. This means that the raster will mark out land areas, and

the features will be neatly outlined with colors matching their plate IDs. We

can do this with ocean plates as well, using another raster (it’s probably best

to place the water layer below the land layer in the list, to avoid confusion when ocean

crust starts subducting).

Hopefully that should make things a bit clearer moving on.

Splitting Comoving Plates

So we know how to tie plates to move together at the start

of the simulation, but what about when we want to rift them apart later on?

Like, say, our Cratons B and C?

To start out with, the procedure is similar to creating our

first rift: We already have a failed rift between B and C, so let’s copy the

geometry of that and extend it outwards (you can use the “Insert Vertex”

tool (“I”) to add new vertices to both ends of the line) But we want it

to extend not only across the continent, but all the way to the mid-ocean

ridges and subduction zones on either side—that is to say, across the whole

tectonic plate.

Make the rift with a beginning at this new rifting point,

have the old failed rift end at the same time, and make new failed rifts

branching out from this new rift (we only need them on land). We can also have

the old rift from the start of the simulation disappear a timestep or two after

it formed to avoid unnecessary clutter and confusion.

Then we can split the continent and other polygonal features

that cross the rift (ocean crust, island arcs) like we did before, by copying

each feature twice and altering the copies to match the shapes of the old

features on either side of the rift, but with different plate IDs.

But rather than having the original features end at the

point of this rifting and the copies begin at the same time, we can just delete

the originals and have the copies exist from the beginning (whenever the

original feature formed), such that there were always two features with

different plate IDs but they were moving together until now. This preserves the

in-program age of the features, which can be useful with “color by age” display

functions later on.

|

| Split the features at the point of rifting (left) such that they exist as separate features from the start (right). |

At least, we can do this with ocean features; for continents

we’ll probably have to use the “original ends as copy begins” option to account

for deformation in collisions later on.

For features just on one side of the plate, we can just

change the plate ID if necessary, rather than creating a copy. For polyline

features that cross the rift (e.g. that eastern subduction zone) select them

and use the “Split Feature” tool (“T”) to split each into two

features, and change the plate ID of one.

With the features sorted, next we have to edit the rotation

file. Open “File” -> “Manage Feature Collections” (“ctrl-M”)

and save “rotation.rot”. Then open “rotation.rot” in a text

editor.

Find the latest position of the plate you want to split from

its conjugate plate, other than its position at 0 Ma. In this case, we haven’t

moved plate 300 (relative to its conjugate plate) since the start of the

simulation.

Copy that line above, and change the time to that of the

rifting event.

Leave the file open and go back to GPlates. Open “Reconstruction”

-> “View Total Reconstruction Poles” (“ctrl-P”). This will

open up a window showing a list of plates in a cascading tree, showing which

plates are the conjugates of which other plates. Find the plate you want to

split from its conjugate (300 in this case) and look at the last 3 columns,

under “Equivalent rotation rel. anchored plate”. This shows the current

position of this plate relative to whatever plate we’ve set to be the anchored

plate, which by default is 0, the immobile rotation axis.

Create a new line for your plate at the point of rifting, above

the line you just made, and input the same plate ID and time, but copy over the

“lat”, “lon”, and “angle” values from those columns in

GPlates, and set the conjugate plate to “000”. Then copy this

line above again and set the time to “1.0”, or replace a position for

this plate with that time if you already have one.

Save “rotation.rot”, and in GPlates reload it in the

“Manage Feature Collections” window. You should now be able to move the

plate independently of its former conjugate.

You’ll have to add new flowlines, and perhaps remake some

old ones—in this case, the flowlines between Continent A and former Continent

BC have to be remade to connect Continent A to each of the new continents

(splitting the original rift may help).

We’ve also made a triple junction in the mid-ocean ridges

here; When making new ocean crust features, we’ll have to project out their

edges so that they meet roughly in the middle, accounting for the different

speeds of the spreading plates.

We’ll then have to add new flowlines here (3 with 1 point

each, 1 for each plate-plate boundary) to track the position of this extending

section of the mid-ocean ridge, and be sure to trace over them as we add more

ocean crust in the future.

Rifting often comes with changes in direction, so watch out

for new regions of subduction—such as along Continent B’s northern shore here.

Making a New Plate

So that all works to split an existing plate away from its

conjugate, but what if we want to create an entirely new plate partway through

the simulation? What if, for example, we want to split off the eastern part of

Continent C into a microcontinent?

Again, the procedure starts out pretty similar to previous

rifting events: Mark out a rift, tracing any available failed rifts (though you

don’t have to follow the whole rift, you can leave a section behind on one side

or another), and create new failed rifts. Those on the microcontinent side

we’ll give a new plate ID; say, “301”, as a small, probably ephemeral

plate split from plate 300.

For features crossing the rift, create a copy on the side of

the existing plate (Continent C) as you would normally. But for the side with

the new plate (the microcontinent) select the feature and use “Copy Geometry

to Digitise Tool”. Move the vertices to trace out the feature on the new

plate’s side of the rift, as you would with a copy, and then create a new

feature with most of the same properties as the original feature—feature type,

time of appearance—but the plate ID of the new plate (301) and, where

appropriate, a new name (say, “Microcontinent 1” for the main landmass).

We might as well also make a new feature collection for microcontinents, as

opposed to craton-containing continents, and add them to the list of polygons

using the land raster.

We have to do this process—copying geometry and making a new

feature rather than just directly copying the old feature—for every object on

the side of the new plate, even if they don’t cross the rift. Simply changing

the plate ID of a preexisting feature causes it to move elsewhere on the globe,

due to how the position is recorded as a combination of original location and

subsequent rotations.

Now, save “rotation.rot” in the “Manage Feature

Collections” window and open the file in a text editor. Add in two new

lines for the new plate at time 0.0 and the time it rifts from the other

plate (1850.0 here). Give it a position of “90.0”, “0.0”, “0.0”

for lat, lon, and angle as all the other plates start out with, and give it a

conjugate plate of “000” at both times.

Save the file and reload it in GPlates. Now open “Reconstruction”

-> “Specify Anchored Plate ID…” (“ctrl-D”) and enter the plate

ID of the plate your new plate is splitting from (300).

Then open “Reconstruction” -> “View Total Reconstruction

Poles” (“ctrl-P”), find your new plate (301), and look at “Equivalent

rotation rel. anchored plate”. Open “rotation.rot” in the text

editor again, and create a new line for the new plate (301) under the

existing lines, with the same time as the rifting event, the lat, lon, angle

position from the window in gplates, and the old plate (300) as the

conjugate plate. Then copy that line and change the time to the beginning of

the simulation (2000.0).

Save the file and reload it in GPlates. Open “Specify

Anchored Plate ID…” again and set it back to “000”. If you scroll

back through the timeline, you should see that the new plate properly follows

the old plate before the rifting event, but can be moved independently

afterwards.

Subducting Ocean Crust

We’ve covered just about every case of divergent boundaries,

but let’s start thinking more about convergent boundaries. Adding subduction

zones around the exterior of the initial supercontinent is easy enough, but

sooner or later you’ll have to add them between your continents, in the area

covered by new ocean crust. In fact, you should make a point of doing so every

other timestep or so, to add a bit of variety to the process rather than just

marching from one supercontinent to the next.

How new subduction zones form is, as I’ve mentioned in the

main tutorial, not settled science. For our purposes, you can either extend an

existing subduction zone or create new ones at transform rifts. You should

prefer to divide old ocean crust from either newer ocean crust or continents,

but you can cut through similar-age crust where necessary. As a generally rule

of thumb, try to make sure that any ocean crust more than about 3-400 million

years old is heading towards a subduction zone.

In this case, Continent A has been turning north, putting

pressure on the northern side of its attached ocean, so let’s make a new

subduction zone through there.

This, of course, cuts off some of the ocean crust on

Continent A’s plate. For these sections, make a new ocean plate just like we

made that microcontinent plate before (though in this case there’s no need to

bother with a rift feature, as there will be no mid-ocean ridge to keep track

of). Call it, say, Ocean i, with plate ID 101. I’ve also switched

subduction zones to all display as blue to stand out more.

|

| For whatever reason GPlates picked the same color for plate 101 as for plate 200 (green), but you can tell where it is by the color and direction of the flowlines. |

As we move forward in further timesteps, the ocean plate

will by pulled into the subduction zone, faster than it was moving with the

continent before, and the continent itself will also be somewhat pulled by the

new subduction zone. The opening of a new subduction zone should always be

accompanied by a shift in motion of nearby plates.

Once a section of the subducting plate has completely passed

through the subduction zone, we can set that feature to end to clear up some of

the clutter. But at the same time, new ocean crust will continue forming at the

mid-ocean ridge. With subduction zones on both sides of an ocean basin this can

form a stable “conveyor belt”, with new crust being formed just as soon as old

crust subducts. In this case, with subduction on one side, the mid-ocean ridge

is being pulled towards extinction.

The general rule of subduction zones is that there must

always be ocean crust feeding into them. It can come in directly or at a high

angle, and it can slow to a crawl, but you can’t pull crust out of the

subduction zone. This is easy enough to say now at the start with the tectonics

of the exterior ocean left unmapped, but it can be tricky to pull off once the

entire planet is covered in new plates. In particular, watch out for those

subduction zones on the trailing edges of plates; the ocean crust has to move

towards the subduction zone faster than the subduction zone is receding

away.

In this case, it doesn’t take long for ocean i to be totally

subducted; in one more timestep, the mid-ocean ridge has passed through the

subduction zone. There’s no need to even make a new section of ocean crust for that plate at

this point; we can just set every feature in the plate to end at this point.

This means Continent B’s plate is now being subducted, and

it can be expect to accelerate towards the subduction zone. But the ocean crust

on A’s side of the subduction zone isn’t getting any younger; in cases like

this with an offshore subduction zone, it’s fairly common for another

subduction zone to open up behind it along the coastline, pulling the outlying

subduction in towards shore until it collides with the continent. But in this

case we’ll leave the situation as-is in order to avoid having too many moving

parts in the next section (though over longer timescales, you’ll probably find

that this process helps “clean up” odd subduction zones and islands that are

tricky to deal with otherwise).

Colliding Continents

Continent collisions are, as a rule, messy affairs, and it’s

worth taking our time to move through them. I still make major plate motions in

50 My timesteps, but I then make some changes in finer 10 My steps.

So in this case, we have Continents A and B barreling

towards each other, with an island arc “trapped” between them.

Moving one timestep forward causes the Continents to

collide, with several of their features overlapping—an unphysical situation

we’ll have to resolve. Collisions don’t always end neatly at the end of a

timestep, like this one has; You want the movement rate to be consistent with

the previous timestep, but you don’t want to end up with too much overlap;

cratons in particular shouldn’t overlap each other. This might require you to

move the plate at some point during the timestep, rather than at the end.

First, that island arc: go back through the timestep and

figure out exactly where along the other continent it is colliding.

|

| Beginning (left) and end (right) of the island arc's collision with Continent A |

Then, at some point during the collision, make a new feature

all along that boundary, representing the accreted terrane formed from

the crust of the island arc. Even though we haven’t been recording the growth

of the island arc after its first appearance, take its age into mind; older

arcs will contain more crust and create larger terranes.

Create the feature:

- Feature type “ContinentalCrust”.

- Plate ID of the continent it’s accreting to (so, 100 here for Continent A)

- Beginning at the point of this collision.

- Name it after that date of collision.

- Create a new feature collection for accreted terranes.

Once that’s done, add that feature collection as an input

for the land raster, and have the island arc end at the same time as that new

terrane appears.

By the way, if you have an island arc colliding with an

island arc, this can create an accreted terrane as well on one of the plates (If

it’s two plates subducting a third between them, place the terrane on the plate

with younger crust in the area, with the subduction zone on that plate

surviving while the other is lost), unconnected to any continent. Usually this

terrane should end up accreting onto a large continent before long, but that

may not happen by the end of your simulation.

With that done, we can move forward to the main part of the

collision at the end of the timestep. When continents collide, much of the crust between them is

compressed and deformed; here, we’ll account for that by redrawing the borders

of the features involved such that there are no overlaps between crust

features.

Select one of the features; I’ll start with Continent A.

Copy it’s geometry, and then move some of the vertices in the new polygon along

the collision boundary such that they create a new ragged boundary roughly

halfway between the boundaries of the overlapping features (you can add some

vertices as well). But some of the compressed crust will be squeezed out to the

sides, so you can expand out the features to either side of the boundary.

Create a new feature with all the same properties as the old

feature you’re copying, but beginning at the point of this collision. Then edit

the old feature such that it ends at the same time.

Repeat this for all the other features deformed by the

collision (in this case, Continent B, the new accreted terrane, and the island

arc on Continent A’s side), making sure that there are no gaps left along the

collision boundary (unless there’s a substantial trapped sea) but no overlaps

between crust features. No major gaps or overlaps, anyway; again, don’t spend

too long trying to get everything to match up perfectly. Note that it’s not

unusual for small features, like that trapped terrane, to moved completely

outside their original position in this process, given that we’re not

simulating the whole process of continuous deformation.

Cratons do deform a little in reality, but not much; for

this simulated process, you should be able to leave them alone, and if that

ends up with them overlapping features outside they’re continent, then you’ve

overlapped the colliding continents too much.

The downside of this process is that it alters the age of

the features. This is an issue only if you want to use some display options

that depend on the age of the features. For example, some of the expanded

continental crust is now overlapping ocean crust features, but I want to

preserve the ages of those. To deal with those, I can split the ocean crust

features into 2 features—one containing all the crust still in the ocean, the

other containing the crust that is now overlapping the land—and edit the one

overlapping the land to end at the point of collision.

Finally, clean up the subduction zones—edit those now

overlapping the landmasses to end at this point (use the “Split Feature”

tool (“T”) to cut those only partially overlapping and make only the

overlapping sections end) and add in extra sections as necessary to fill gaps

along the boundary.

That handles all the features, but the very last step of

colliding the plates is tying the plate IDs together. This works just like

breaking them apart, but with different conjugate plates. In this case, let’s

set plate 100 as the “parent” plate and make plate 200 the “child” plate, tying

it to move with plate 100 as its conjugate plate.

Save the “rotation.rot” file and open it in a text

editor. In GPlates, set the parent plate (100) as the anchored plate, and find

the child plate (200) in the “Total Reconstruction Poles” window. In the

rotation file, make a new line for the child plate (200) above the latest line

in the simulation (which should be the plate’s position at the end of the

collision; 1650.0 Ma in this case) and fill it in with the position data for

that plate under “Equivalent rotation rel. anchored plate” in GPlates,

with the parent plate’s ID (100) in the conjugate plate column. Also copy this

position, with the conjugate plate, to the plate’s position at 1.0 Ma.

Save the “rotation.rot” file, reload it in GPlates,

and set the anchored plate back to 0. You should now find that moving the

parent plate moves the child plate with it. This doesn’t mean you can’t move

the child plate at all; if the collision doesn’t finish in one timestep, you

can continue to move the child plate relative to the parent plate in the next

timestep, as the plates move across the globe together (you will, of course,

have to deform the features again at the end of that timestep to handle this

continued collision).

In this case, there’s still that long subduction zone to the

south where Continent A’s plate is subducting Continent B’s. In an actual

simulation, I’d deal with that either by forming a new subduction zone along

the south coast of combined Continent AB, pulling in the island arc to collide

with the coast and eventually pulling Continents AB and C back together; or I’d

rotate Continent B around until it eventually collided with Continent A’s south

coast. But this tutorial is almost over, so I’ll just ignore them for the sake of simplicity.

Splitting Plates After a Collision

When continents collide, the suture remains as a weak point

in the crust, and new rifts can form there later on (this doesn’t usually

happen immediately, but we’ll do it for the purposes of the tutorial). I won’t

go through the whole process here—it’s essentially the same as the earlier

section on splitting comoving plates. The one note I want to make is that the

rift shouldn't pass exactly over the suture point between pre-existing features;

there is always some exchange of “territory”.

Split the features crossed by this rift much as we

“deformed” them in the last section:

- Copy their geometry.

- Create new features occupying the space of that old feature on either side of the rift (with plate IDs to match the plates on that side).

- Have these new features begin at the point of rifting.

- Edit the old feature to end at the point of rifting.

I’ll leave it up to you whether or not to create a new

feature collection for fragments of continents broken away from the main

continent features.

When you’ve done all that and edited the rotation file to

split the plates again, they should be able to split with everything on the

correct side of the rift.

Not only is this accurate to how old sutures rift in reality, it's also a good way to gradually add more detail to your coastlines.

Marking Resulting Features

That about covers the whole process of plate motion in

GPlates; Continue on to the end of the simulation, following the broad outlines

of tectonic processes as outlined in the main tutorial

and the specific steps as outlined in this one. But when you’re done, you still

have to go back through the timeline and add some features that result

from these plate motions; orogenies, LIPs, and hotspots.

Adding Orogenies

Orogenies are major mountain-building events that

appear along convergent boundaries. As mentioned in the other tutorial, there

are 4 major varieties:

- Andes-type orogenies, which form thin mountain ranges on any coasts with subduction just offshore.

- Laramide-type orogenies, which form broader ranges when subduction is particularly rapid or where a mid-ocean ridge is subducted (the science is unsettled and both are probably contributing factors, but the latter possibility is easier to spot in GPlates).

- Ural-type orogenies, which form thin ranges in simple collisions between landmasses.

- Himalayan-type orogenies, which form broad, high plateaus in more complex or energetic collisions between landmasses.

In GPlates, we can start out by placing Andes-type orogenies

as polygonal features near any coastlines with subduction zones at the start of

the timeline. You can use the measuring tool to get a sense of proper size; 100

km from the coasts and 100 km wide is a good standard.

Create the feature:

- “OrogenicBelt” as the feature type.

- Plate ID matching the landmass it’s on.

- Beginning time matching that of the subduction zone causing it.

- Whatever name you like (“orogeny” and date of formation works fine for me).

- A new feature for “Active Orogenies”.

Once you’ve created your orogenies, open the layers window

(“Window” -> “Show Layers” or “ctrl-L” if you don’t

already have it open), find the layer for active orogenies, select “Fill

Polygons” and then “Set Draw style”, and set it to black in the “SingleColour”

list.

The orogenies will now stand out as black shapes.

Continue forward in the timeline, adding orogenies to the

landmasses as new subduction zones appear. We needn’t bother with them on

island arcs, though; these can be assumed to always have active volcanism and

young mountains—at least until they collide with a continent, at which point

they’ll form a new Ural-type orogeny anyway.

Where it gets interesting is when landmasses collide. First

off, whenever an island arc collides with a landmass (or another island arc),

the accreted terrane that forms should be essentially entirely covered by a new

orogeny.

Then when major landmasses collide, an orogeny should form

along the border between plates after you’ve deformed the colliding

features, encompassing all the regions and boundaries that have been deformed (to

clearly see the boundaries after collision, set the time to slightly after the

collision; e.g. 1649.99 Ma rather than 1650.0 Ma).

If there are existing active orogenies in the region—from

previous stages of the collision or subduction preceding it—you should stretch

this orogeny to include them. But sometimes when there’s a lot of overlap

between the plates prior to deformation you’ll find that a preexisting

Andes-type orogeny extends too far over the boundary to be reasonable, when in

reality it would have been compressed into the mountain range during the

collision. To handle these cases, you can split the feature into 2 copies; one

encompassing that area that will continue on, and another encompassing the area

you want to remove, which you can edit to end at the time of the collision.

|

| The section of the orogeny to end at the time of collision |

But unlike an Andes-type orogeny, these collisional

orogenies are short-lived. Gradual deformation and uplift can continue for a

while, but sometime after you’ve concluded the collision in GPlates—50 My is

good if that’s your timestep—we can consider the orogeny no longer “active”,

and it will start to erode down.

To show this, we have to replace these “active” orogeny

features. Select the features in the orogeny (there will often be multiple),

copy their geometries, and create new features—same feature type and plate ID,

but beginning at this point (50 My after the collision ends) and placed in a

new feature collection for “Former Orogenies” Edit the old features to

end at the same point. If an orogeny involved in this former collision still

has active subduction along part of its length, you can split it into copies;

one containing the ongoing active orogeny and one to be replaced by a former

orogeny.

In the Layer’s list, find “Former Orogenies” and

select “Fill Polygons” and “Set Draw Style…” In the “FeatureAge”

section, select “Monochrome”. This will cause the features to begin

black, like the active orogenies, but fade to white as they age.

(While you’re here, you should also set “Active Orogenies”

above “Former Orogenies” in the layers list, such that any new orogenies

appear over older orogenies in the same region.)

The only issue with this is that once the feature is over 450

My old, for some reason the feature flips back to black. This is long

enough that the mountains should be pretty much eroded flat, but the “roots”

(tough rock formed under the surface) could still be uplifted and exhumed by

later events, so we should still keep track of them. To do this, replace the features

again with features in a new feature collection for “Old Orogenies”, and

color them white (and place the layer for that feature collection below active

and former orogenies).

Of course, sometimes rifts will split these orogenies. We

can deal with that like most rifting of features—by copying the geometry and

creating new features on either side of the rift. The catch is that instead of

having new features begin at the point of rifting and the old features ending,

you need to have the new features retroactively begin at the same time as the

old feature did, such that it displays properly.

The distinction between Andes-type and Laramide-type

orogenies—and between Ural- and Himalayan-type—is hazy, and really these are

endpoints on a continuum rather than distinct category. For subduction

orogenies, just generally add thicker orogenies on leading edges for

faster-moving continents, and particularly thick ones when a mid-ocean ridge

subducts (and make the thicker inland regions turn to former orogenies when

these conditions end, while retaining a thin coastal range). For collisional

orogenies, consider multi-stage collisions, high collision speed, and many

pre-existing sutures between features in the collision area all as factors that

can thicken the orogeny.

Adding LIPs

LIPs—Large Igneous Provinces—are much briefer events than

orogenies, but can still produce substantial highlands of igneous rock, so are

worth recording. In a broad sense they can be treated mostly like orogenies,

but not as persistent and not as deterministically placed; some will be

associated with major rifting events, especially supercontinent breakups, and

some will appear more-or-less at random. Many LIPs in reality appear in the

ocean, but for our purposes we need only record those on land.

At the end of each timestep whether or not you want an LIP

in that step, and if so draw it as a feature:

- Feature type “LargeIgneousProvince”.

- Plate ID of the landmass it appears on.

- Have it exist for only 10 My, starting or ending at the timestep boundary (the latter case—ending at the end of the timestep—is appropriate if you want an LIP immediately preceding a rifting event that starts at the beginning of the next timestep)

- Place it in a new feature collection for “Active LIPs”.

This approach means the feature will show both in still

images at each timestep, and in a continuous video of the whole process.

As with orogenies, you should create a “former LIP” feature

in a new feature collection that remains after the LIP concludes. You can also

have “old LIPs”, but LIPs older than 450 Ma don’t have much impact on modern

geography—they’re not often uplifted and exhumed like orogenies—so it may not

be worth recording them anyway. Also like orogenies, whenever a former LIP

splits you have to split the feature such that the proper age is recorded; if

an LIP forms in association with a rifting event, you should just make it as

two features on either side of the rift from the start, though it should still

initially appear as one object straddling the rift.

How you display LIPs is up to you, but I like to display

active LIPs as filled orange polygons, and then just keep former LIPs invisible

most of the time to avoid confusion with orogenies—you’ll need these LIPs as

reference for making topography later on, but they’re not as important as the

orogenies.

Adding Hotspots

Hotpots are concentrated regions of volcanism, similar to

LIPs but at a smaller scale and often more persistent. Most are immobile; they

do not move with the plates in the crust (some do move, or are specifically

associated with tectonic activity on the surface causing tears in the crust,

but we’re just marking the immobile ones here). The landforms they create on

the surface, however, do move with the crust, creating distinctive “island

chains”.

Hotspots don’t typically persist for more than 1-200 My, and

the landforms they create don’t often last long after they cease, so we only have

to mark those hotspots appearing in the last few timesteps. Some will be

“leftovers” of LIPs, appearing where the LIP formed but remaining static as the

plates move. Others will appear more-or-less randomly.

To make a hotspot, set the time to where you would like the

hotspot to appear (they shouldn’t appear only in 50 Ma timesteps, but finer 10

Ma timesteps should be fine) and select the “Digitise New Multi-point

Geometry” tool (“M”). Place the hotspot (or cluster of

hotspots, which isn’t unusual) where you would like it to start. Create the

feature with “HotSpot” as the feature type, a plate ID for a plate that

doesn’t move (I use “1”, same as for my rifts), a start point at the

current time, and an end point in the “Distant Future”. Place it in a

new feature collection for “Hotspots”. How you display it is up to you,

but I find that purple is a good color that stands out from the others I’ve

used so far.

Now we need to give it a trail, which is similar to the

process of making flowlines. Select your hotspot feature, copy the geometry,

and create a new feature with the feature type “MotionPath”. Give it the

ID of the plate overlaying the hotspot (in this case, the hotspot appeared

under ocean crust in plate 300) and for the “Relative Plate ID”

give it an ID of “0”, for the immobile rotation axis (I think you could

use another immobile plate, if you added it to the rotation.rot file with 0

rotation at the start and end of the timeline, but I haven’t tested this).

In the next window, press “Add” and under “Insert

multiple times”, set “From” to the time the hotspot appears, “to”

to “0.00”, and “in steps of” to “10.00”. Like I said, much

like how we made flowlines. Press “Insert in that section and then “OK”.

Finish creating the feature, with a new feature collection for “Hotspot

Trails”

When that’s done, you should find that you can move the time

forward and see a trail emerging from the hotspot, matching the motion of the

overlaying plate, and with arrows every 10 My pointing in the direction of the

plate’s motion--away from the current position of the hotspot. Again,

display is up to you, but I chose a gold color here.

The island chain will follow this trail, with islands

growing older and more eroded down further from the current position of the

hotspot. Like former LIPs, I tend to keep these trails invisible most of the

time, but hold onto them as references for making topography.

Adding Mid-Ocean Ridges and Plate Topologies

I actually wasn’t aware of these features when I made the main

tutorial (all the divergent boundaries there were drawn in by hand) but they

may be of use to other people.

First off, it might be nice to have a persistent mid-ocean

ridge feature. The process is almost identical to making flowlines: Go back to

the point of initial rifting and select the rift feature. Copy its geometry,

then create a polyline feature—not a multi-point feature, as with

flowlines. Make the feature type “MidOceanRidge” and then in the

properties window select “Half Stage Rotation” under the “Reconstruction

Method” window.

Have this feature begin at the time of rifting, and give it

the plate IDs of the plates on either side of the rift, just as with flowlines.

Give it a new feature collection (For display, I like to color them red) and

you should now see a persistent line at the center of the ocean basin with

ocean crust originating from it.

As with flowlines, you may have to draw in extra sections by

hand at each timestep by triple junctions.

Once you have all those in place, you can use them in